Like so many others, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about the last concert I heard in person before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down live music for what has now been nearly a year. It was March 10, 2020, at Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, and the young American pianist Conrad Tao was performing selections from his 2019 album American Rage. Alongside Copland’s Piano Sonata, Tao performed two works by American composer Frederic Rzewski: Which Side Are You On? and The People United Will Never Be Defeated! In keeping with his album’s title, Tao imbued both Rzewski selections with furious romantic intensity.

Throughout the early days of the pandemic, I listened to Tao’s prescient American Rage on repeat. Over the summer of 2020, as the pandemic raged on and racial tensions boiled over across the U.S., Tao's red-hot take on Rzewski’s politically charged works seemed to mirror our contemporary American ethos.

And so, in November of 2020, with the tenor of American politics continuing to boil over, I was eager to dive into another pianist’s take on Rzewski’s latest protest-song-inspired composition. But Songs of Insurrection, 32-year-old Los Angeles-based pianist Thomas Kotcheff’s album featuring Rzewski’s 2016 solo piano collection of the same title, caught me off guard. In place of unbridled fury, this new release offers stubborn, willful, determined ruminations. In place of unchecked rage, Kotcheff’s Rzewski evokes disciplined, sustained action in pursuit of change.

And so, in November of 2020, with the tenor of American politics continuing to boil over, I was eager to dive into another pianist’s take on Rzewski’s latest protest-song-inspired composition. But Songs of Insurrection, 32-year-old Los Angeles-based pianist Thomas Kotcheff’s album featuring Rzewski’s 2016 solo piano collection of the same title, caught me off guard. In place of unbridled fury, this new release offers stubborn, willful, determined ruminations. In place of unchecked rage, Kotcheff’s Rzewski evokes disciplined, sustained action in pursuit of change.

Inspired by Walt Whitman’s poem of the same title, Rzewski’s Songs of Insurrection is a collection of seven pieces, each built around a protest song from Germany, Russia, the U.S., Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Korea.

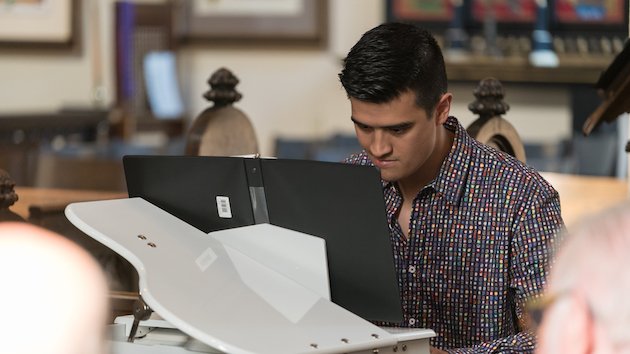

With sparse pedaling, unhurried tempos, and pointed melodic clarity throughout, Kotcheff’s exquisitely detailed performance of the songs often evokes the aesthetic of Stravinsky’s neoclassical piano works. Rests are carefully observed and notes are released with as much clarity of intention as they are depressed. Melodies speak simply, articulately.

This almost neo-Baroque interpretation suits Rzewski’s compositional choices here stylistically. While still centered around clear themes and variations, the composer treats these 20th-century melodies like Baroque ones with fugal and fantasy-esque passages. As in much of Bach’s keyboard music, intense emotions are here embedded in carefully crafted textures. To hear them and ultimately feel them, every detail must be observed.

Like Rzewski, Kotcheff is a pianist/composer. In each one of these pieces Rzewski leaves room for performer improvisations, which he labels as optional in the score. We can be thankful that Kotcheff never opts out. His improvisations feed off Rzewski’s variations and are complex and thought-provoking in their own right. In several instances –– as in the third track (Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around) –– they are climactic, organically leading to the reflective, coda-like endings indicated in the score.

Yes, rage can fuel political and social upheaval. But real change often follows long periods of sustained, disciplined, determined effort. Kotcheff’s extraordinary attention to detail here illuminates both the fiery emotion and surgical precision inherent in Rzewski’s compositions, as well as in any meaningful insurrection that leads to lasting social change.