In the year 1900, three lighthouse keepers disappeared from the Flannan Islands lighthouse, off the west coast of Scotland, never to be seen again. After reading of this mysterious incident, the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies composed a chamber opera, The Lighthouse, to his own libretto. Like many other operas, The Lighthouse ventures into the realm of the supernatural, or madness, or both. Opera Parallèle’s imaginative new production of the opera, seen at its opening on April 29, 2016, is as gripping as can be — beautifully performed and leaving audiences wondering just what happened.

Economically written for three singers and an orchestra of 13 players, this harrowing 80-minute work opens with a prologue during which three officers sent to investigate the disappearances are questioned by a court of inquiry about what they found. The three officers, played by tenor Thomas Glenn, baritone Robert Orth, and bass David Cushing, give slightly different answers to the questions. This might be mere accidents of memory, or the differences might be meaningful.

After the court renders an open verdict, the action segues without a break to the main body of the opera, called “The Cry of the Beast.” The three officers remove their uniform coats and are transformed into the lighthouse keepers Arthur (Cushing), a religious fanatic, Blazes (Orth), a crude man with a hidden criminal past, and the seemingly normal Sandy (Glenn), who tries to defuse the tensions between Arthur and Blazes.

But new tensions arise when Sandy and Blazes play a card game that ends in accusations of cheating, and here begins their descent into madness. Each of the lighthouse keepers sings a song, composed by Davies as pastiches of easily recognized musical styles: a folk song with banjo and violin accompaniment, an operatic aria, a revivalist hymn. In two of these songs there is a secret about the singer, and as they remember their secrets, they begin to see ghosts. Arthur’s hymn leads him to imagine that the Beast — presumably the seas monster from the Book of Revelation — is about to rise up from the sea and take them. Soon Sandy and Blazes join him in his terror, and from this delusion comes the final tragedy of the opera.

You’d be right in thinking that The Lighthouse sounds a bit like a mashup of Peter Grimes and The Turn of the Screw. Nonetheless, Davies’ vocal writing and his dissonant, skittering musical language are thoroughly distinct from those of Britten. And The Lighthouse is quite the equal of Britten’s operas in its dramatic force and otherworldly beauty.

As we’ve come to expect, Opera Parallèle brought strong musical and theatrical forces to bear on The Lighthouse. Powerhouse conductor Nicole Paiement led the tiny, brilliant orchestra crisply, pacing the opera for maximum musical and dramatic tension while realizing every last detail of the complex orchestration.

Glenn, Orth, and Cushing made a fine ensemble as the three officers and neatly distinguished the personalities of Sandy, Blazes, and Arthur from one another. Cushing, a singer new to me, has a spectacularly beautiful and sonorous bass voice, one I hope to hear much more often in local opera productions.

Z Space, where the opera was performed, has a large, open area for its stage, but there are no wings, traps, or flies for storing scenery or allowing for invisible entrances and exits. Director Brian Staufenbiel rose to this challenge by staging The Lighthouse with an economy matching its musical scale.

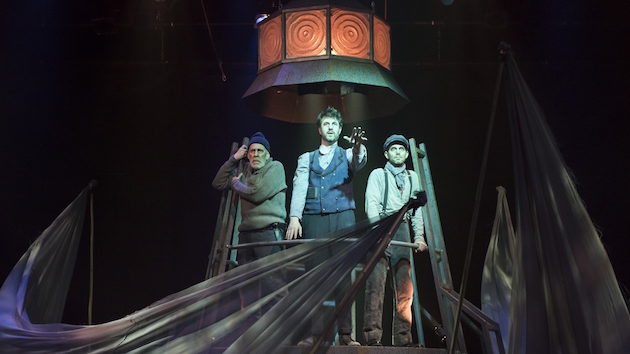

A single metal structure, cleverly repurposed as needed, serves as both the boat and the lighthouse. Four, black-garbed individuals, called fabric dancers in the program, manipulate large swaths of fabric that divide up the stage into different sections, act as waves or the sides of the ship, and, spookily, portray the rats inhabiting the lighthouse. The fabric dancers worked well from my vantage point in Row H, and at times were almost invisible parts of the scenery, but another audience member told me that the fabric dancers weren’t dramatically effective or convincing from her seat at stage level.

The beautiful score and gripping plot left this listener wondering why The Lighthouse isn’t performed more frequently. The compact cast and orchestra, the minimal set requirements, and the opera’s brevity would seem to make it a perfect fit for our time- and money-challenged era.