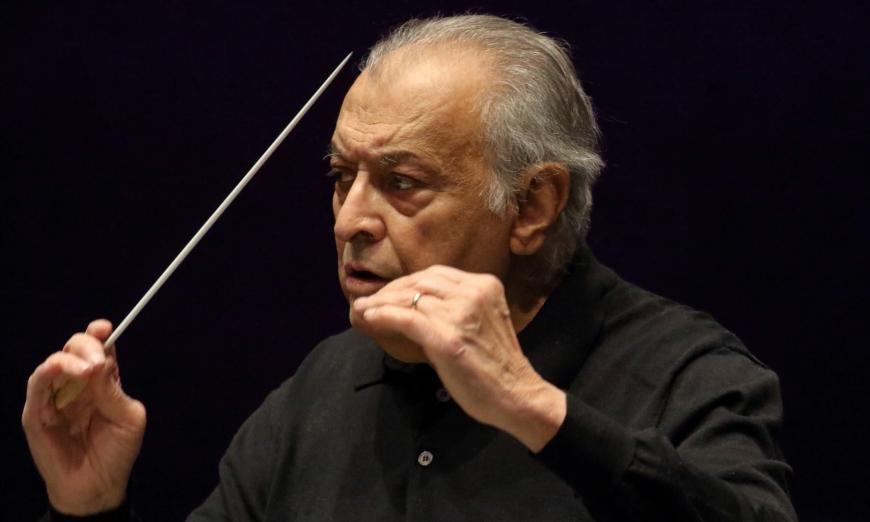

When the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s esteemed conductor emeritus, Zubin Mehta, settles in for his annual two-week visit to his old orchestra at Walt Disney Concert Hall, he usually brings big-thinking pieces from the top drawers of the basic repertoire. But now and then, he can throw a curveball, like in 2020 when he led a minicourse in Germanic music history from Richard Wagner to Anton Webern.

So in that spirit, after magnificent performances of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 the previous weekend, Mehta made a bold choice for his second program (heard Sunday afternoon, March 12), juxtaposing two radical pieces from adjoining centuries — Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique (1830) and George Crumb’s song cycle Ancient Voices of Children (1970).

The Crumb work may not be an out-of-the-blue selection for Mehta; he told me that the piece has been part of his repertoire for some time. But its strange sonorities, played by a tiny seven-member ensemble plus two voices, make for maximum contrast with the huge orchestra that Berlioz used for his strange (for the time) orchestrations. There you have the connection — unusual sounds from different means, along with a belated, and needed, opportunity to remember Crumb just after the first anniversary of his death last year at age 92.

Set to the words of the martyred Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, Ancient Voices of Children proved to be a breakthrough for Crumb in terms of exposure outside the relatively small circle of new-music devotees. It seemed right for the times in America, representing both a revolt against the perceived loss of innocence during the Vietnam War and the serial method of writing music that handcuffed mid-20th-century composers who wanted to be taken seriously. The 1971 premiere recording of Ancient Voices on a Nonesuch LP reportedly sold more than 70,000 copies — a Klondike strike for an avant-garde composition.

For me, Garcia Lorca’s words — which are barely intelligible in any case — are secondary to the sparse, broadly paced, and (as so often with Crumb) haunted sonic landscape that can be savored as pure abstract sound. The soprano soloist is asked to sing into the innards of an amplified grand piano, with the natural resonance of the soundboard producing a long, ghostly decay that lasts an eternity. She sings, speaks, sing-speaks, and howls in Spanish, phonetic sounds, and vocalise, at one point through a megaphone. A boy soprano sings offstage through a microphone at first, emerging into view only at the end of the piece. The pianist bonks out percussive sounds on the amplified prepared piano and also on a toy piano; the oboist doubles on harmonica. The percussion players are quietly busy with a wide variety of instruments, including the tapping of a bolero rhythm on snare drum. As bizarre as the means can be, everything is subsumed into the overall mood.

Ultimately, in the last song Crumb pulls out his biggest surprise by having the oboe virtually duplicate the haunting melody of “Der Abschied” from Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde. This cameo perhaps also influenced Mehta’s choice of Crumb’s work as an echo of the gigantic Mahler symphony from a week before.

The announced soprano Nadine Sierra couldn’t make the gig due to illness, so her replacement, the Puerto Rican soprano Sophia Burgos, gave an astounding performance, running through all of Crumb’s oddball processes with abandon. Sebastian Dolinar, from the Los Angeles Children’s Chorus, was the dauntless boy soprano, and Mehta kept his physical gestures to a bare minimum. It was all quite intoxicating.

Symphonie fantastique took up the bulk of the program— and it was a bulky performance in terms of sheer weight. The dark-colored, heavyset, now more refined sound that Mehta elicits from the LA Phil allowed for ample muscle, especially in the brass, in the extroverted fourth and fifth movements yet also for painstakingly nuanced passages in the strings everywhere. The tempos were a little slow, most noticeably in the second, fourth, and fifth movements, except when the finale’s coda took off at a rollicking pace.

I couldn’t help but go way back to a recording of the second movement from Aug. 1, 1961 — a year before Mehta became music director of the Phil at age 26 — that was released for the first time last summer on the big Hollywood Bowl 100 boxed set of LPs. Quite a contrast. Through the low-fi sound, you can hear a youthful exuberance that on Sunday had been replaced with a relaxed, assured sense of grace — and also much, much better orchestral playing.

Two more notes of interest: While Mehta used a cane to walk to and from the stage for Mahler two Sundays ago, he didn’t need one last Sunday. Also, Mehta’s next two weeks with the LA Phil in December are scheduled to revert entirely to the basic repertoire: Beethoven’s Symphonies Nos. 3 and 6, Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. No risk-taking adventures in programming in store, then, but it will be another chance to catch a once dashing, now grand old maestro hitting his peak as an interpreter of the classics.