Photo by Mats Lundquist

Accustomed as we have lately been to 100-minute Mahler symphonies, the Verdi Requiem, and other lengthy events, San Francisco Symphony's subscription concerts this week presented a contrast.

From your timekeeper:

- Beethoven, Symphony No. 8, 26 minutes

- Henri Dutilleux L’Arbre des songes, 24 minutes

- Haydn, Symphony No. 99, 22 minutes

Even adding the 15-minute intermission didn't stretch the entire concert beyond an hour and a half. Back in the good old, leisurely days of the 19th century, that would have been the first part of a three-part evening.

Related Article

A Mahler Third Symphony Like No Other

September 21, 2011

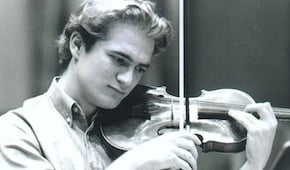

Renaud Capuçon Free Download

October 18, 2011

But what of quality? Going long, going deep. On the podium, Alan Gilbert has visited here before, but this was his first time since his elevation two years ago as music director of the world's second-greatest orchestra. That, of course, is the New York Philharmonic. (No. 1 is still the Berlin, I think, allowing that such generalization is always open to debate.)

More than before when he led fine but unexceptional performances — such as at Festival del Sole six years ago, when Gilbert was in constant orbit between Stockholm and Hamburg, with sidetrips to the Santa Fe Opera — the conductor this time established close and effortless contact with the orchestra, polishing off the two similar classics with panache.

The Beethoven and the Haydn are both late works, both sunny, graceful, and rhythmically joyful pieces. Conducting with small, but clear gestures, Gilbert had the strings together as they are at their best outings; woodwinds shone, the brass at times did not.

In the Beethoven, the closing of the Allegro was magical, the Allegretto lived up to the scherzando marking, the last two movements were exactly right, all elements in place but also lively and fresh.

If anything, the Haydn made an even greater impression, melding the rich orchestral sound with a spectacularly steady forward motion, pulling melodies, harmonies, and rhythms together — leading up to the delighful, irresistible finale.

Dutilleux, turning 96 in January, wrote the violin concerto for Isaac Stern in 1985. Renaud Capuçon, the soloist in Davies Symphony Hall, was using Stern's 1737 Guarneri del Gesù "Panette," also the instrument at the Paris premiere and when Stern played the work at the only other San Francisco performance, in 1988.

L’Arbre des songes (The Tree of Dreams) has a dreamlike, eerily quiet opening, with Robin Sutherland's delicate piano ostinato becoming part of the orchestral fabric. Capuçon's solo entry and his nonstop, virtuoso playing provided perfect clarity in the devilishly complex score.

For a composer who counted Fauré and Ravel among his contemporaries and friends, the Dutilleux work shows virtually no trace of their influence. With a slight nod to Bartók and — especially — Debussy, this is all Dutilleux and no one else.

Capuçon and the orchestra — with clarinet, bass clarinet, harp, and oboe d'amore having special roles — maintained convincing control over the ever-shifting inner voices of this engaging work.

You have to read the program, or the score, to realize that there are such adventurous components of the work as "controlled music of chance, the notation confined to pitches or pitch areas, with few rhythmic indications ..." All I heard was beautiful music, a concerto both resolutely modern and completely accessible.

And that's the short and the long of it.