Compare music to poetry, and eyes begin to roll — for good reason. We’ve all read (and some of us committed) the strained metaphors, misty-eyed rhapsodies, and moody nonsense that can reveal a whole lot more about a critic than they do about the music.

But sometimes poetry is right out there, front and center, and can’t be ignored. That was the case, in several senses, with the opener of the San Francisco Symphony’s all-French program at Davies Symphony Hall, heard Saturday. First, there were the title and movement descriptions of Henri Dutilleux’s Tout un Monde lointain (A whole distant world), for cello and orchestra. The lines come from the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867).

As for how the poetry informs the music, or the other way around, the composer himself isn’t much help. The quotations were applied after the piece was finished. And it was only because he’d been asked to write a ballet commemorating Baudelaire 100 years after his death, Dutilleux later acknowledged, that the poet was even on the composer’s mind when he set out to write a cello concerto for Mstislav Rostropovich. (The ballet project was never completed.)

Related Articles

No Swan Song for Cellist Gautier Capuçon

The celebrated cellist reflects on his career so far and his very eventful SF Symphony debut in 2009

Century-Old S.F. Symphony Is Younger Than Springtime

A look back at the SF Symphony's first 100 years

Truth be told, a listener can enjoy this enchanting work without ever entertaining a thought of Baudelaire. The intrinsic expressiveness and aural imagery, the sense of simultaneous compression and expansion, are present from the plangent opening lines by the cello, fetchingly set off by brushed snare drum and cymbals, to a feathery, trilling-into-silence close 35 minutes later. Along the way, Dutilleux engages the ear, mind, and heart with his lyrical excursions, rhyming echoes, deftly interlaced themes, overall economy of means, and a rich orchestral vocabulary. The five linked movements are set off, like poem stanzas, with end-stop fermatas.

OK, I’ve said it, after all: Tout un Monde lointain has all the virtues of a tightly made and transporting poem. Originally written in 1968–1970 and revised in 1988, the piece made a vivid impression in its first-ever appearance on a San Francisco Symphony program.

None Better Suited

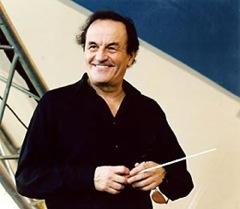

It’s hard to imagine a more persuasive advocate for the cause than the soloist, Gautier Capuçon. Like a great verse reader, he was simultaneously alert to both the broad arc and the tiniest nuance. His acute sensitivity was perfectly matched by conductor Charles Dutoit and the orchestra. A unity of purpose prevailed throughout. Even when Capuçon played in whispers, they rose through the band’s transparent shimmers of sound. And when the volume and urgency peaked, both parties lit up and went for broke, together.

This greatly gifted cellist has the kind of tone that could make a listener swoon if he were only playing scales — a tone tender and bright, firm and deep, lustrous and sinewy. Still, gorgeous as it was, rising out of his dark-hued instrument, Capuçon’s sound was never an end in itself. In the opening movement — “...et dans cette nature étrange et symbolique,” for those keeping track of the Baudelaire lines — the soloist conjured a mood both willful and quizzical, assertive yet yielding. His pizzicatos were plump and ripe. His glissandos, at the end, were dead ringers for a slide whistle. Humor and mimicry were another part of his endlessly strong game.

The concerto wound through contrasting episodes, turbulent and becalmed, whimsical and mysterious, blunt and oblique. The fourth movement was especially choice, with its lovely, quietly pained cello theme wandering over a tentative xylophone ostinato. Then the final movement went strutting off from there in march time.

The performance made you want to immediately hear Tout un Monde lointain all over again. And hear it played by these very musicians. Not that it would sound exactly the same way twice, of course. Music, like poetry, teaches us what to listen for on repeated hearings, after we’ve been changed a little by that first encounter.

In Storytelling Style

The second half of the program was devoted to Berlioz’ Symphonie fantastique. Dutoit, counterintuitively, offered up this allusively programmatic work in prose. Tempos were deliberate to the point of plodding. Phrases were left relatively uninflected or shaped. Details blended into the whole or sometimes stood out on their own, blunt and unadorned.

This wasn’t all to the fault, by any means. Dutoit seemed intent on telling a story, complete with offstage characters — the gongs that announce the Dies Irae theme were ominously out of sight. By the end, in a raucously explosive “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath,” the audience seemed caught up in the narrative, greeting the climax with hearty cheers.

Yet it was hard not to regret the shortcomings along the way. “A Ball” had long patches that were either dry or downright sluggish. “Scene in the Fields” bogged down in thick textures and stately detachment; even the timpani thunder at the end seemed too precise and contained. And the brasses in “March to the Scaffold” lacked a caustic bite on their first entrance.

Raw and exciting as it was at certain memorable moments, this was not a Symphonie that made the listener want to turn back the score’s pages and start again.