The Los Angeles Philharmonic canceled its concerts all the way through the end of December and maybe beyond. Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion are shut down. Hollywood Bowl is now a big empty concrete shell scalloped from a hillside. With little on the horizon beyond a profusion of stopgap streams this summer, let’s take a long look back to a time half a century ago when things were starting to hum in symphonic life here.

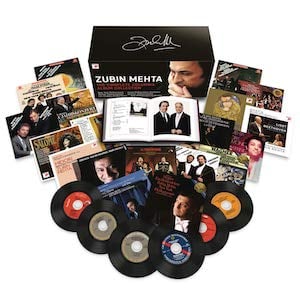

The catalyst is the release last month of a giant 38-CD box of the complete Decca recordings of Zubin Mehta and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, dating from 1967 to 1978. These recordings — some of which are appearing for the first time on CD in the U.S. — illustrate why Mehta’s 16 years here was the first in a series of transformative eras for the Phil.

The catalyst is the release last month of a giant 38-CD box of the complete Decca recordings of Zubin Mehta and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, dating from 1967 to 1978. These recordings — some of which are appearing for the first time on CD in the U.S. — illustrate why Mehta’s 16 years here was the first in a series of transformative eras for the Phil.

The number 26 figures prominently in Philharmonic numerology. Mehta was only 26 when he became the Phil’s music director in 1962 — as was Simon Rattle when he became co-principal guest conductor, and Myung-Whun Chung when he became assistant conductor, and Esa-Pekka Salonen when he made his North American debut here, and Gustavo Dudamel when he was appointed music-director-designate.

In the first couple of years since his ascension, the young maestro from Bombay (now Mumbai) found himself learning and conducting some items of core repertoire for the first time, leading the transition from the aging Philharmonic Auditorium to the glittering new Pavilion — and exuding an unforced charisma, dynamic stick technique, and energy that was something new in L.A’s symphonic life. Also, Mehta was the first Asian conductor to make a major impact in the West, just ahead of Seiji Ozawa, and that made him even more mysteriously glamorous. If New York had its Leonard Bernstein, then L.A. countered with Mehta — and the long campaign to prove to the cultural lords of the East Coast that this city had more to offer than just Hollywood glitz really began here.

Yet Mehta had more serious musical intentions as well. His idea was to bring something of the sound and feeling from his Viennese training to the West Coast, hiring musicians and acquiring instruments that would get him closer to the ideal. I’m not sure he succeeded entirely in that. What I hear on these recordings is not so much a Viennese sound, nor the unfair tag “Hollywood Sound” that had been plastered on the Philharmonic by out-of-town critics, but a Mehta sound — ample-bodied, excitable, occasionally muscular, but almost always with a musically flowing quality in lyrical passages, not afraid of beauty nor blunt force when necessary. Which brings up a funny anecdote: The Phil’s late principal trumpeter Thomas Stevens once told me that Mehta hired him because he thought that Stevens’s tone quality sounded Viennese. But Stevens said that he was actually trying to sound like Miles Davis!

Prior to the Mehta era, the name Los Angeles Philharmonic had barely any presence in record shops — mainly a scattering of 78s and LPs under Alfred Wallenstein after World War II, or discreetly backing local celebrity soloists like Arthur Rubinstein and Jascha Heifetz. (Members of the orchestra had recorded with Bruno Walter and Igor Stravinsky, but always disguised as the Columbia Symphony.)

One thing that Mehta absolutely had to do in order to elevate the Phil’s profile was to get the orchestra on records in a big way. Three years after a one-off session for RCA Victor shortly after the Pavilion opened, Mehta got his new record company Decca (London in the U.S. then) to sign his LA Phil to a four-year initial contract — the first time an American orchestra had been offered one by a major European record label.

With today’s profusion of excellent halls around the region, it’s hard to recall that L.A. once lacked a really good space for an orchestra to play in. Since the record made in the Pavilion was sonically mediocre, Decca had to scrounge around, finally deciding to record the Phil in UCLA’s Royce Hall to the amazement of many who had deplored the hall’s acoustics prior to its renovation in the ’80s. They flew in 56 cartons of first-class recording equipment from London, and brought the orchestra forward onto a stage extension on the floor of the hall. The first three LPs came out in Nov. 1967 with a burst of publicity — and instantly, the LA Phil became a factor on the global record scene.

Listening now, I’m struck by how dry Royce sounds on these early recordings, almost like a film soundstage in pre-Dolby days — and I wonder whether that perception helped to trigger the pejorative references to a “Hollywood Sound.” Yet the box suggests that Decca’s engineers got better and better in learning how to record in Royce, producing marked improvements in resonance and detail. Soon they were able to get impressive results that wowed the audiophiles.

Also, the ensemble playing of the orchestra was steadily improving; in general, with a handful of exceptions, the later the recording date, the better they sound — proof that Mehta’s relentless program of orchestra-building was working. Compare the recordings of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 from 1967 and 1976 — the only piece they recorded twice — and you’ll hear a definite upgrade in ensemble, sonics, and even enthusiasm in the remake.

One great, prophetic building block that Mehta put in place was bringing the orchestra into the present tense of its time — observing trends and occasionally venturing out on a limb. For the first time, Mahler became a big part of the LA Phil repertoire. Astutely, the LA Phil recorded a bass-rich, splendidly-paced recording of Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra a month after the release of the film that featured its “Sunrise” opening, 2001: A Space Odyssey. The success of that LP led to recordings of four more big Strauss tone poems. The Mehta/LA recordings of Charles Ives’ Decoration Day and Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2 and Carl Nielsen’s Symphony No. 4 came in the wake of the booms for both composers in the 1960s.

Not much of Mehta’s explorations of new music made it onto disc, but there weren’t many orchestras then brave enough to record Schoenberg’s 12-tone Variations for Orchestra — nor Edgar Varèse’s Arcana, Intégrales, and Ionisation, a splendid hi-fi showcase that was reportedly difficult to record. The Phil’s principal timpanist William Kraft was also a composer, and Mehta thought enough of his music to record his Concerto for Four Percussion Soloists and Orchestra and to commission and record Contextures: Riots — Decade ’60, a piece that caught the anxiety of 1968 days after Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination. That LP put Kraft on the international map, where he remains today.

Once Ernest Fleischmann came on the scene as the Phil’s executive director and boss of the Hollywood Bowl, he and Mehta cooked up extravaganzas like the 12-hour Beethoven Marathon on the day of his 200th birthday in 1970, a crossover concert on TV juxtaposing the Phil with hot bands like The Who and Santana, and the expansion of the Tchaikovsky Spectacular into a hellzapoppin’ fireworks show that always sold out the Bowl. Mehta’s final season unleashed a laser concert at the Bowl in Nov. 1977 that included suites from Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind; the latter film had just come out that month. Decca rushed the Phil into Royce to record them, the first classical conductor/orchestra team to take John Williams seriously. Mehta even started a short-lived music training program for gifted children from economically depressed backgrounds — a precursor to today’s YOLA.

Time marched on, Mehta’s ambitions grew, and he left to take over the New York Philharmonic in 1978. The biggest L.A. project, an excellent complete cycle of the six Tchaikovsky symphonies released the year after Mehta left, went almost unnoticed by the international press. By 1984, nearly three-fourths of his LA Phil recordings — the most any conductor made with the orchestra — had gone out of print; I suspect one reason was that digital sound had arrived and Mehta’s analogue catalogue suddenly was regarded as sonically outdated. But it has gradually dawned upon orchestra buffs that Mehta’s L.A. Decca sessions captured much of his best work. When he rerecorded some of these pieces later with other top orchestras, in most cases the results were not as electrifying as what he had achieved in Los Angeles.

Time marched on, Mehta’s ambitions grew, and he left to take over the New York Philharmonic in 1978. The biggest L.A. project, an excellent complete cycle of the six Tchaikovsky symphonies released the year after Mehta left, went almost unnoticed by the international press. By 1984, nearly three-fourths of his LA Phil recordings — the most any conductor made with the orchestra — had gone out of print; I suspect one reason was that digital sound had arrived and Mehta’s analogue catalogue suddenly was regarded as sonically outdated. But it has gradually dawned upon orchestra buffs that Mehta’s L.A. Decca sessions captured much of his best work. When he rerecorded some of these pieces later with other top orchestras, in most cases the results were not as electrifying as what he had achieved in Los Angeles.

The last sessions the orchestra made under Mehta for Decca in March 1978 produced what I think was their finest hour-and-a-half on records — Mahler’s Symphony No. 3. Mehta waited until near the end of his L.A. term to record Mahler, and everything seemed to have come together in this Third — tempestuous energy and drive, great sonics, but also refinement, poetry, stillness. The final movement, a long, slow, loving meditation, strikes me as Mehta’s fond farewell to his orchestra.

Now, as Conductor Emeritus of the LA Phil in his 80s, Mehta faces an orchestra much improved over the one that he led long ago, playing in a space (Disney Hall) that projects their sound better than the Pavilion stage ever could. Yet you can still hear the Mehta sound fire up whenever he conducts here — albeit with the old exuberance toned down, but now an even surer sense of structure and depth of feeling. These recordings remind us how that flame was lit.