The greatest future hope for classical music is that composer and multi-instrumentalist Angélica Negrón is not one-of-a-kind.

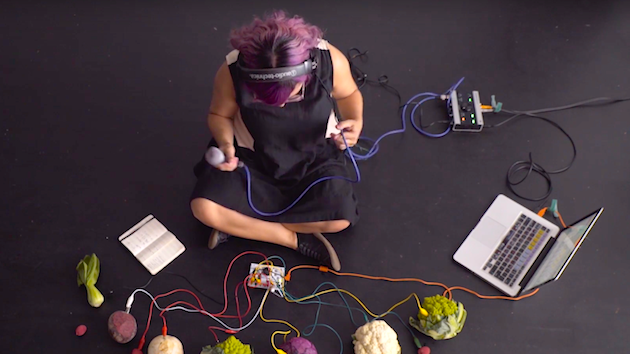

For all the many words and high praise written or spoken by musicologists, reviewers, journalists, or her fans, the truest thing that can be said about her music is that it is unpinnable. And Puerto Rican-born Negrón herself is a moving target: Classically trained in violin and piano, she never thought of herself as a vocalist early in her career. Now, she mostly sings and plays the accordion when performing with the electronic indie band Balún, of which she is a founding member. As a composer, she’s just as likely to use electronic hardware, toys, plants, crumpled paper — any sound-generating tool falling into her curious hands — as she is to write for cello, violin, tuba, clarinet, string quartet, or an orchestra.

Negrón’s commissions and past or upcoming premieres arrive from Bang on a Can All-Stars, Kronos Quartet, American Composers Orchestra, LA Philharmonic, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra, San Francisco Girls Chorus, and the NY Philharmonic Project 19 initiative, among others. She has written music for documentaries, films, theater, and modern dance. Negrón has a master’s degree in music composition from New York University and pursued doctoral studies at the Graduate Center (CUNY). Also an educator, she is a teaching artist for the New York Philharmonic’s Very Young Composers program and co-founder with Noraliz Ruiz of the Spanish immersion music program for young children, Acopladitos.

In an interview, Negrón speaks about projects that include Marejada (Waves in the ocean), a 50 for the Future commission from Kronos; Otra Cosa (Another thing) for Prototype Festival’s Modulation series; the Landfall soundtrack (written for Cecilia Aldarondo’s documentary about post-Hurricane-María trauma in Puerto Rico); and The Island We Made, a new piece for Opera Philadelphia premiering as a digital film on March 19.

While writing Marejada during the pandemic, there was actual physical separation of members of the quartet and, in the digital realm, time-lag divisions that made it impossible to synchronize the ensemble playing your music live. Are there specific compositional elements you used in scoring the piece aimed at addressing the realties?

There are things I write in the score as notes to the performers. For example, there are abbreviated gestures with the bow and I write, “Swim into the sound.” Be together, but go on your own journey. I was conscious as a composer that I’m often having complete control of how things line up in the way I write most of the time, which is measured, and traditional in terms of scoring. But because it was commissioned to be performed in a virtual video conference platform, there was no counting at all. I had to find ways to change how I interact with time or what togetherness means. They’re playing on the same platform but not together physically in the same space, which is a challenge.

[I asked] “What happens if we attempt to be together, attempt being the key word, and then embrace that we’re not going to be together?” That happens gesturally in a moment that everyone is playing the same rhythm, the same pitches, in pizzicato. (The score) says, “Start together, attempt to play at unison and enjoy the process of failing.” It’s the idea of almost celebrating the fact that it’s not going to line up perfectly. At the same time, let’s consider there’s an inherent beauty in not having control of every element, of every sound or word.

What is unison? Has the pandemic shifted for you as a composer and performer the meaning of cohabitation in time, space, or communication?

That’s a great question. The obvious answer is unison is being in a new space together, obviously spaces that are virtual. What it means to be in unison is to be in that process of investigation and reckoning with the fact that the unison now is different. But also realizing there could be another form of unison. Maybe there are things we can learn from that new place? It’s letting go of what normal was and what I thought it meant to be together. And survival is redefining what unison means — for my own mental sanity. Also redefining it to allow me to enjoy other people’s company and making music together.

Do you enjoy making music with other people in the visual realm during the pandemic?

It’s challenging, because I talk about finding the beauty in it but I don’t think in terms of silver linings. There is nothing beautiful in such a tragic time we’re living in with so much loss. At the same time, we have to be here. I have to find what gets me up every morning: making music with other people and enjoying music that others make. When that is no longer part of every day or looks different, the survival instincts kick in. The curiosity-driven artist mind of problem-solving and attempting to connect is the thing that makes me try to find new ways to enjoy what we have.

Speaking of “everyday” brings to mind church. Church caused the music of Bach, Beethoven, and many other classical composers to be familiar to society across class spectrums. Church had much to do with African American spirituals, gospel, or union workers’ songs in the 19th century, and in 1960s civil-rights protest songs. Today’s “church” of the streets shaped hip-hop, rap, and more. What is the “church” for your music?

I love this question! Definitely growing up in Puerto Rico, religion is culturally present. It certainly was that way with my family. Church every Sunday as a place to make music together and enjoy it, as a place to be annoyed by the lady next to me who would do something weird with her voice, as a place of inherent complexity. That’s definitely one of the spaces in which music sounds like a place; a complex one, but a significant one that had an impact. Oftentimes, it was not my decision to be there. Your family goes; you have to go.

Now, I think about consent around sound and how that shifts. I think of where I lived in Puerto Rico. It was really noisy, cars moving with really loud music going all the time, sometimes fireworks and you didn’t know if there are gunshots too. I’m a person who since I was a child has been really sensitive to sound. Loud sounds I can’t anticipate give me great anxiety. So church was a sacred space. That’s why I started composing: it was because it was literally a place of escaping that conflict that was outside. It was a place I could close the door of my bathroom and record layers of violin. I could sit for hours with a harp and record sounds not coming from the strings but from other parts of the instrument. It was a place of intercession and not having to live with other sounds that gave me anxiety.

There’s sometimes in my pieces an escapist impulse in them. I embrace them and find them problematic as I struggle with that tension, but it all comes from a deep place of making sounds in order to find a place that feels safe.

How often and in what ways does your work reflect or convey reaction to the world that shapes your ideas about identity?

There’s something about having to define myself and my music early on — feeling that pressure — that has made me aware of identity in my career. I was told my music doesn’t sound Puerto Rican, or where are you in your music, we can’t place it. I struggled with that for a long time and now, I don’t struggle but I think about it a lot. It makes its way into whatever I create, whether it has to do with my Puerto Rican-ness or my upbringing or something that doesn’t at the surface relate at all to identity but I feel it’s there. I feel compelled to share the multiplicity of my identity. To celebrate that and not conform to one box or another. I have many different interests. I love writing music for kids, electronic music for plants, opera for a drag queen, writing for an orchestra. All those things can feel like, oh, she’s all over the place, what’s the focus here? But this fluid identity I have and embracing that is what ties it all together.

Will you talk about the role of the visual environment and its interplay with the auditory elements in your work?

I’m a visual person. I first studied violin and then music composition and at the same time was pursuing a degree in film. I’m also intimidated by a blank page of sheet music. It’s a way for me to imagine something in shapes and colors rather than pitches or staff. That’s almost always a first step to get ideas out in a way that feels more immediate than notation. I don’t have synesthesia but I definitely have associations with colors and textures when I hear things. I showcase that in the form of instead of playing keyboard, I will play a plant. By using a plant, what can that add to the narrative of the piece? Especially when I’m singing, all of my lyrics are in Spanish, so for people who do not speak Spanish I’m trying to find entry points that are visual that evoke connections and create meanings that are open-ended enough for everyone to make but also connect them to the very personal seed that brought the song to life.

Collaborating: What has been your experience?

I love collaboration and feel lucky to have talented friends. When I start a piece, it’s common for a friend’s work or someone I don’t know but love their work to come to mind. Sometimes that starting point gets abstracted into music and becomes just the impulse that starts the piece, but sometimes it feels it also wants to be a part of the piece. That was the case for Marejada, the piece I wrote for Kronos. [Written for Kronos Quartet/Kronos Performing Arts Association’s 50 for the Future project, Marejada since August 2020 has had more than 130 downloads in 20 countries/territories worldwide.]

This was very early in the pandemic and I was struggling to find joy in anything. To be honest, I was completely overwhelmed with this commission because Kronos is a huge part of my musical formation. I was finally commissioned to write for them — and I had a short amount of time at my lowest creatively! I don’t create from a place of fear, usually.

Thinking about it, I remembered my friend, Justin Favela, who had been following this project — he creates piñata paintings with tissue paper — and just his colors were already making me smile. I was thinking about how he uses something similar to paint-by-numbers in his work and that was an abstraction. My interaction at that moment with everyone on the project was an abstraction. For example, I had never met some of the Kronos members. [Favela’s Seven Seas Beach, Puerto Rico artwork that was created for the project can be seen as the virtual Zoom background used by the members of Kronos while separately recording Marejada.]

What approaches or principles guide your decisions to use the human voice, to write lyrics or not, to include breathing sounds. Is it instinctive, determined primarily by the commission, or other parameters?

It comes from a place of instinct. When I’m composing I sing almost every part. Even an orchestra piece, I’m singing the oboe, tuba, clarinet. I like to embody the instruments, imagine myself in every layer of the piece. It also comes from wanting to share something very personal. I’m thinking back to my band Balún — we were [all] instrumental, and then I started having ideas for lyrics and melody. But I was scared to sing. so the first song I wrote, I asked another friend to sing. Then slowly that evolved. It was coming from a deep place from the human body. Even though I was afraid of sharing it though the vessel of my own body, I felt compelled.

Sometimes voice comes with a choral commission, but sometimes voices make their way into pieces that are instrumental. I want that intimacy and texture of the human voice. Most of the music I really love has voices in it. It’s an instrument but also there’s ability to add words or play with how people get access to that personal space.

Maybe it’s in Spanish or maybe it’s a made-up language that I have my own meanings for that stays with me, which gives you hints in how I set the text, but not all of it. A part of it stays with me. If there is a moment that needs to be all about clarity, maybe English will get me more understanding with people who will be my audience. Same thing with titles; there is musicality inherent in words. I like to play with that as a reflection of the complexity and identity of someone who is an American citizen but also an immigrant.

When approaching a new tool — software program, toy, instrument, sound generating device — are you more apt to just pick it up and play, or research, seek a mentor, pursue instruction? Is there an approach that is most trustworthy?

I like to think I’m the person who will do all the research, but I’m definitely not. I do best in play mode: mess around with it and see what it wants to do. It connects to my formal training as a violinist and feeling there was a right and wrong way and being uncomfortable with that. There was technique and excellence, words with a weight to them. There was not knowing what it meant to love music, to be at home exploring a new tool. The way to be successful was not through creativity, it was doing something right.

When I approach a new tool, it’s going back to that 12-year-old violinist who is confused and not having fun. For me, that comes with an asterisk because I also consider myself to be a nerd and I do research things online. But the moment of starting to use it for me — I learn my best when I’m in a playground rather than school.

What is and isn’t working to move classical music forward; to make it vibrant for young musicians and new audiences without losing traditional artistry and audiences?

What’s working is to realize the models we had before were not working. Awareness that leads to action is something that’s long overdue. In that tension of someone like me that grew up in a traditional background playing violin in orchestra, people like me are realizing the things we took as excellence or as a canon — there are things like inequities that (have) made those a reality. A reckoning of the things I love that are problematic, and things I don’t love but that are making sense — there’s a space there where really creative work can happen.

By things not working I mean big institutions and the way they’re built. They’ve been structured to keep certain people outside of them: composers who are not white or male. I’m talking about the realization that those things are not leading us to the place we want to be as a society. From that place there are conversations long overdue, and it’s bringing awareness especially in BIPOC artists to think of our work differently. A piece I wrote last year, Say Something in Spanish, is something I wouldn’t have thought of four years ago. I would have been grateful just to write a piece, to have a “seat at the table.” But this moment that has been building makes me think of my practice in different ways and makes me hyperaware of why I’m invited into those spaces. As an artist, what’s interesting is to have fun with that and play with that.

Among classical-music composers, whose work are you able to return to over and over and hear new things?

I have to be honest and say I don’t listen to music from the Classical period. I grew up immersed in it and in a way sheltered from other kinds of music. As soon as I found a way out, I never came back to it. That’s not to say if I’m at a concert and there’s a Beethoven symphony I can’t enjoy it, because I do. The oldest thing I listen to or look at a score for would be Impressionist composers [such as Claude Debussy]. Shostakovich? Oh yes, I love Shostakovich. [Alexander] Scriabin. If a composer’s name starts with an “S,” I probably love it. Shostakovich’s violin concerto was the first music I heard that I connected to. It was something that translated to sarcasm, defiance; witty with an edge to it I hadn’t felt with orchestral music.

And among living music composers?

Julia Wolfe. I find myself constantly going back and finding new things. There’s a shared sensibility I can feel through her music. There’s restlessness, again, an edge. And something genuine in work that is serious but she’s not taking herself or it too seriously.

What can you tell me about Otra Cosa?

It’s a reaction to me wanting to collaborate with women after coming from male-dominated projects. It’s also a response to humor as a form of resilience, which I find in artists from Puerto Rico. Lido Pimienta is a Colombian singer who’s brilliant but doesn’t sing songs other people write. I asked her if she’d sing something I wrote for her.

So it was born out of conversations about experiences I and these two women had had. [Puerto Rican librettist/illustrator Mariela Pabón was also a collaborator] Mariela finds a way to get to dark or sad things through humor that makes me see things in it I hadn’t seen before. There’s joking, but serious joking about how people mispronounce our names, but also those moments about hearing fireworks or gunshots. These things have bad truths in them. Finding humor in them, I’m interested in those places and what’s there.

The Landfall soundtrack?

It’s a project dear to my heart about life after Hurricane Marià. It’s about communities that are making change happen and looking for sustainable ways. It was special to go to Puerto Rico and record [the album] with friends who played with me in orchestra when I was growing up. I did not compose the score and then go record it. I spent two days in the studio with musicians who are dear friends. We talked and made sounds. What would it sound like for a viola to make the sound of an electric generator? What if we want to be birds with the harps? That collaborative, intuitive process of getting to a score, I had never done that before and I think it was only possible with my people.

The Island We Made?

I think this piece very much connects to this idea we talked about yesterday of carving out shielded spaces of shelter. In this case, a space where you’re free to be whoever you truly are but also a space for embodying and processing unvoiced conversations with loved ones, for meditating on the limitations of relationships and for honoring the women that have shaped us. I wanted this song to feel like a nurturing embrace but without losing the complexity inherent in the act of raising and taking care of someone.