Countering the pandemic’s paralyzing effect on musicians due to concert and commissioning cancellations, composer/pianist Gabriela Lena Frank is moving swifter than a meteor.

Since March 2020, the Berkeley-born musician has won a $250,000 Heinz Award, initiated a goal-exceeding Covid Response GoFundMe campaign that resulted in Pairings (an online series of 65 new works featuring performer-composer teams), expanded her staff, and launched an online learning program offered by the Gabriela Lena Frank Creative Academy, which is based in Boonville, a small rural town in California’s Anderson Valley.

Adding more streak to Frank’s shooting star is her need to address through her work vital issues such as gender equity, socioeconomic and educational opportunities for musicians who are people of color or people living with disabilities, and climate change.

Frank, 48, was born with profound hearing loss and says in a phone interview that when playing the piano without a hearing aid, she only feels the keys and is aware of the choreography of her fingers. Her hearing aid is an essential tool that, combined with lip-reading, also allows person-to-person conversation. Her work graces the repertory of San Francisco Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Boston Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Detroit Symphony, among many others.

Centering her work as a composer and director of the academy on a core, touchstone philosophy, Frank says, “The purpose of art is to reveal and to reveal in ways that add extra poignancy to a story or certain experiences.”

Congratulations on winning the Heinz Award. How will you use the funds?

I see myself as a storyteller, or even a witness. I’m witnessing this person who is a Berkley-born, multiracial woman. I happen to have a disability from birth as well. When you are this package of traits, the music that comes out can land in certain categories: commenting on gender, race, social and economic inequities. Those are all-natural byproducts of living my life. I’m also representing the stories of many Americans that live in this wonderful country that’s also a flawed country. I’ve been able to articulate that more clearly during the last four years, as we’ve been in a divisive stasis.

With the Heinz Award and its timing coming after the last four years, I’m thinking about why am I composing now? I had certain reasons when I was younger, and now that I’m moving into the second half of my life, what are my reasons? It’s all the [issues]. . I’m almost 50 years old and I’m determined to make it to 100. I want those to be rich years, to keep witnessing, keep talking about experiences that I have.

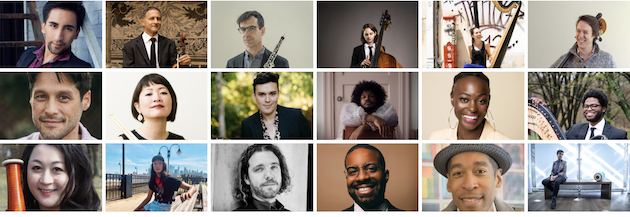

During the pandemic, you launched a GoFundMe initiative to support performers, GigThruCovid. What are a few highlights of the program? How many artists are involved?

We (engaged) about 65 performers and another 65 composers, so we’re over 100. We have approximately 65 premieres online. The compositions were donated and completely voluntary. I didn’t expect such a high turnout. We had about 68 composers in the academy and I was hoping maybe 20 would volunteer their time. This was in the early days of Covid when we didn’t know how severe it would be. I couldn’t just watch it: how it impacted performers. I had to do something. I said I’d pledge some of my personal money to get it started and then we raised the rest.

I was blown away when in one weekend almost all of my composers said they wanted to be involved. It ended up being huge. The staff and I, this has consumed our lives for the last few months to get this [work] into the hands of our performers. It’s only a small sum of money — $500 they received — it was about the work. They wanted the dignity of work, to perform, to be paid fairly. They worked with the composers on music written purposely for them.

One of the hardest things about Covid for musicians is not just losing money, it’s losing our voice. We’re not doing what we’re put on earth to do: to connect with people, tell stories, play instruments, touch people’s hearts. I know that is said romantically, but to be cut off from that — the project was an emotional relief for them too, not just a financial one. Now, we see how dire this emergency is. It’s a serious situation we’re in.

The support for composer/performer teams surpassed the $35,000 fundraising goal, correct? Will new pairings continue?

We passed it and then had people donating more outside of GoFundMe. A few thousand dollars also came in from other routes. Our final fund was close to $37,500. We ended the campaign [when we] released the final premieres. I had to put my staff onto establishing a distance learning program online, so that’s a lot of work. We’re a small, part-time organization and we have to pivot to that program that’s for composers and really reasonably priced.

Speed was vital with the pandemic response program: Did this result in shorter compositions, less experimentation, simpler pieces, or conversely, more risk-taking?

We got a lot of feedback from performers and composers. Many of them told me they were at first apprehensive; putting out something pubic for which they didn’t have a lot of time. And then many of them found it really freeing, saying, “I had to get rid of these voices in my head.” Like, What should this music sound like? What would my teachers think of this? They wrote things that were very pure, from the heart, in the absence of all of these “shoulds.” It should be super hard. I should write something really modern. They found something simpler, and effective ways of sounding virtuoso. Relationships and friendships came out of this. There was no shaming, no finger-wagging.

Were you surprised, or maybe wishing you could participate?

I haven’t had the luxury of writing something quickly and absent of harsh judgement. So that was an unexpected discovery. When I contacted them, I told them “time is going to be tight.” I encouraged them not to write something super difficult, because we want the performers to get to these quickly. We want them to be able to produce these quickly. We can’t wait. But if you look at the music, it’s wonderful, virtuosic, skillfully written, and sometimes [the music] sounds harder than it is. That has taught us something.

The settings [for the videos] were in the performers’ homes, not the stage or a professionalized arena. And it was freeing that it was a gift from the composer to the performer they might not even know. To start off relationships with a new work and a fee, that is a relationship started in goodwill, and that’s not typical of a professional commission which is not a relief effort. Composers said they want to bring that sentiment of gifting and humanity to projects that are professional. It’s a wonderful and unexpected development.

Is there a drawback to compositions offered for free? Might composers be taken advantage of?

The way composers and performers are paid is different. Composers feel the fallout of economic distress a little later. We often get paid half up front for the commission, and then half upon delivery of the score. The first thing to disappear when the pandemic hit us were straight-up concerts [most impacting performers]. Meanwhile, composers were still securing commissions or [had] already been paid half of the money. At the academy, we already had a program that supports our composers and a commission program for our alums. We poured more money into it and made more commissions. This pairing campaign is a program for performers we don’t typically work with. We focused on performers because we already had a way to help composers.

Are any of these early works slated for future development?

Another unexpected benefit of the Covid campaign is that we met performers we didn’t know. They were recommended to us; our network nominated people in need of help. Three performers are now instructors for our distance-learning program. They’re amazing teachers. Those performers were more experienced, but the younger performers, I have ideas brewing. There’s a lot of matchmaking still. I have a young staff and they’ve become more experienced and confident. They're making suggestions for matching performers to composers. This campaign was our energy that went out into the world, but it also came back to us. It matured us and has given us a way to think about future acts of humanity we can be involved with. It was a two-way benefit, as it should be.

Let’s talk a bit about the academy and specifically, the new Tidriks Distance Learning program. It was developed in response to seeing the same course offerings in music academy catalogues and as a response to the climate crisis. What are the greatest opportunities and largest challenges within this program?

I started developing this before Covid. I talked to potential teachers about it as a way to reduce the carbon footprint. Could we cut down on the number of flights in order to teach composers? The original format was that every composer would come to California twice. If I could cut that down to once and make the visit longer, incorporate more activities online, what would that look like? Would it also deepen the experience if there were more classes that could take place even before they came to California? The work they are producing could be in a more advanced stage. And then they could continue remote classes even after they leave and we could pay our instructors for their time.

This was even before I knew what Zoom was or had models for teaching online. I was a newbie. And now the world has changed. I doubled the number of courses I was going to offer in the first year, from about five or six to 12. This is not a pandemic stopgap. It’s a way of teaching we’re going to attain, because I do believe the pandemic is a sign of environmental distress. It’s a disaster that is planet-wide; it’s not regionalized. It’s not just wildfires, windstorms, and hurricanes. It’s got the entire planet in its sights. The classes came from that impetus.

Selfishly, I decide I needed this first year of classes to make me feel I was back in school. To make me a better teacher, better mentor, to address areas that are not in my comfort zone. There are two kinds of courses: practicums for certain instruments; [and] music literature courses. One of my composers is a do-it-yourself punk musician and he’ll be teaching because I don’t know anything about this art form. Same with hip-hop and Carnatic Indian music.

We have special topics [courses]. One is climate crisis specifically for creatives. What can we do as writers, sculptors and composers to address the climate crisis? Both in our habits, but also as messengers to try to shift our cultural thinking about the climate crisis. To aspire, to say we can get control of this. We have technology, know-how — we just don’t have the cultural acceptance of it. Artists have charisma. We have the ability to play violin, create videos, dance. These are areas where I need to deepen as an artist and citizen.

Any plans to retrofit the Bahlest Eeble Readings so they do not have to wait for a Covid vaccine? What is the status of the Eeble and Jeffer Practicums and the Alumni Support Initiative?

They’re not all on hold. Commissions for solo instruments are proceeding. The premiere might be digital but the composers are working. Other things are being retrofitted. The Eeble Readings are on hold. We’ve put the performers for those on speed dial and said you’re next. It’s just a matter of when. We just have to see how the pandemic plays out.

Are there ways you foresee this pandemic reverberating through your work as a composer?

Oh, my goodness. I could talk all day about that. I’m still finding myself in this new world, even if I can’t articulate all the ways today. Generally, it has given me a sense of urgency. The time is now to say the things I need to say. To be even more Gabriela-like.

I believe the science about climate crisis and the science that points to health epidemics to be more likely. I will address those stories I need to tell. Especially for someone who’s been living in a fiery zone for the last four years. I can’t tell you how it might come out, but some of these [issues] were in place before the pandemic. I reluctantly became an environmentalist because of the fires. I had just begun addressing [the] climate crisis in my music when the pandemic hit.

The other thing that came is regarding race: the BLM moment and the necessity for addressing the treatment of people of color and the undocumented, largely Central-American people we have here. My goodness, I’m not going to run out of things to write about.

As you look at classical music and opportunities for young musicians, what do you most hope to see? What do you fear?

I am most fearful we’re going to lose talent in the music industry because of economic needs. They have to take other jobs. Once you leave the music industry, it can be a challenge to still get called, to be thought of for a production. It took the pandemic to show [that] musicians are not supported enough. They shouldn’t have to live a life of [poverty] in order to do what they love. We need to protect them. Until we get to that point, we’re going to lose talented people. If some large ensembles fold, on the whole, orchestras will revive. I’m less concerned about organizations and more concerned about specific artists and people who will have to leave.

What must music institutions and established artists like yourself do to build momentum for classical music and to ensure its future relevance?

We’re talking about a systemic cultural shift that has to [be] happening at the conservatory. We train musicians for a world that has been shifting. We’re training [them] for a bygone era of YouTube and the early 2000s. Now, we’re well into the 21st century, so I’m not sure the fundamental course load is updated enough. We need to teach them about other styles, focus on more than the last 100 years. We need to focus more on citizenship and not take a disdainful view on that. Do they need to spend so many years doing nothing but Bach? Can they get a great skill set looking at other repertoire?

This is a hard shift, because there’s a culture of conservatory life and jobs and ways of doing things. I feel like I’m stepping back through a time machine; back to the ’90s when I was a kid. But this is a different generation and the world has shifted and we’re not cloistered off. If we try to maintain that status quo, it’s to our detriment. I love traditions, but I hope to be part of the conversation for relevance that begins very early. This won’t be solved overnight. We need to take steps. The academy is my small of way of trying to do that; to modernize and offer composers examples of how to be more in step with the times of today.

NOTE: The SF Symphony’s Día de los Muertos program features one of Frank’s compositions — “Danza de los Muñecos” (Dance of the dolls) from her Milagros. The program is available in for free on-demand streaming at the SFS Día de los Muertos webpage and will be broadcast in Spanish on Saturday, November 7 at 11 a.m. on Telemundo 48.