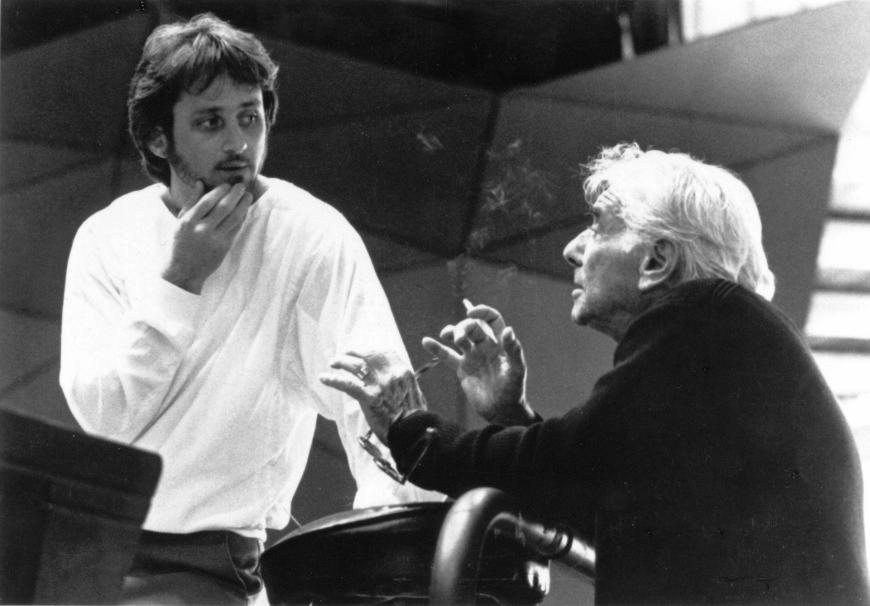

Now in his 32nd year leading Pacific Symphony, Carl St. Clair, who conducts the orchestra in a program of Mozart and Mahler June 23–25, has come a long way from the small Texas town of Hochheim (population a whopping 36) where he was born and raised. And while the late Leonard Bernstein, who died in 1990, referred to him as “cowboy” when they first met in 1985, when the youth was a conducting fellow at Tanglewood, St. Clair wasn’t wearing a 10-gallon hat, sporting spurs, or a giant belt buckle.

The fortuitous meeting was, however, the beginning of a storied career in which he was assistant conductor with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1986) and, from 2008–2010, general music director for the Komische Oper in Berlin. He also served as general music director and chief conductor of the German National Theater and Staatskapelle in Weimar, Germany, where he led Wagner’s Ring cycle to critical acclaim. In 2014, St. Clair became the music director of the National Symphony Orchestra of Costa Rica, a post he still retains.

In addition, the conductor, who recently turned 70, has appeared with notable ensembles such as the New York Philharmonic, The Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Beginning in 2019, the maestro was named “distinguished alumni in residence” at his alma mater, The University of Texas at Austin Butler School of Music. And, for more than a quarter century, St. Clair has had a continuing relationship with the USC Thornton School, where he is artistic leader and principal conductor of the orchestral program.

But it’s with Pacific Symphony that he continues to make his mark. Having forged a strong relationship with the musicians and community of Orange County, his commitment to building educational programs continues to be a vital part of his agenda. He also led the band on its first international tour of Europe in 2006, and in 2018, St. Clair took the podium in his orchestra’s sold-out Carnegie Hall debut, with The New York Times’ James R. Oestreich calling the group “a major ensemble.” The maestro also toured China in 2018, while, back home, he remains a champion of new music.

Speaking with St. Clair by phone from his home in Laguna Beach, San Francisco Classical Voice covered topics ranging from his relationship with Mr. B. (as St. Clair fondly called Bernstein) to his long tenure with Pacific Symphony.

You must get asked this all the time, but how does a boy from a small town grow up to be a world-famous conductor?

I would say my first music came from my aunt, who played the piano and was my piano teacher, and also from the Baptist church I grew up in and on the back porches and front porches. I was 17 when I heard an orchestra for the first time. We didn’t have such things because it’s a farming community, so orchestras were far away from our imaginations.

But the music education was pretty good. We had a little band from the sixth grade, and in junior and senior high, I played trumpet. That’s why music education is a high priority for Pacific Symphony, because even in a small town like that, it helped shape my musical self.

So, from noodling on the piano, blowing a bit of trumpet, and going to college in Texas and then the University of Michigan, you meet Leonard Bernstein. What are some of your memories of him and does anyone else call you “cowboy”?

I was one of the fortunate ones [to meet him] during the last six years of his life. I ended up conducting his very last concert, Aug. 19, 1990. It started when I was a conducting fellow in 1985. Because of that one week, the next summer I was his assistant conductor. We toured together, weeks on end. I consider him a teacher, a mentor, a friend, and someone who motivated and inspired all of us.

I was fortunate to have had him in my life, especially in the last years of his life. He was intent on imparting his knowledge to young musicians, as well as making recordings like mad. It was a very fortuitous time.

And no, no one else calls me cowboy, but that was the first thing he said, literally. I was at Seranak, the [former] home of Serge Koussevitzky at Tanglewood, and I didn’t look like a cowboy from Texas. I didn’t have a hat, boots, and a belt buckle. But since he’d never met anyone from Texas, this intrigued him.

I was selected to conduct a concert for the 85th birthday of Aaron Copland, and our relationship deepened. We went to Vienna on a tour for eight weeks, and the point is, he still plays a huge role in my life, as do all of my teachers and mentors. One mentor and teacher that is still alive is Seiji Ozawa. I was his assistant conductor, and he will be 87 in September.

You probably know that Bradley Cooper is directing himself in a in a biopic of Bernstein, and with the aid of a prosthetic nose, the actor bears an uncanny resemblance to the maestro.

I also understand that Bradley is a classical music fan. I did reach out to [Bernstein’s daughter] Jamie, to see if he needs any gestural coaching if he ends up conducting. I can do all of Mr. B’s moves, but I haven’t heard back, because playing an iconic and musical personality, there has to be a lot of studying going on.

That would be so cool if you ended up contributing to the film. Meanwhile, you’ve got your own orchestra to conduct. Your upcoming concerts feature the twin sisters Christina Naughton and Michelle Naughton, who’ll be playing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 10 for Two Pianos, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 4, with soprano Cecilia Violetta López. Had you worked with the twins before, and how did you decide on this program?

I had never met them, and I look forward to it. They’re terrific, and I love this concerto, so whenever I can, I like to couple Mozart and Mahler, especially Mahler’s Fourth because this, for me, is a perfect combination. It’s his most classical by nature, in terms of shape, form, timing, clarity, transparency. I like that it’s about childlike innocence rather than trying to encompass the entire universe. Mozart’s music is also very innocent, lively, vivacious, enchanting, especially the piano concerto. There’s no darkness, and it’s spiritually very high.

It sounds like a perfect pairing, so what are your considerations for programming a concert in general?

I don’t think so much about programming a single concert, which, of course, comes down to that, but I think about a whole season. We have to reach a balance, then we filter that into each program. This program has three soloists, for example, and we also have to cover new music. We do our best to include BIPOC and women composers, conductors, and soloists.

It’s like creating a season that’s a large feast for everybody, but not everyone is appreciative of everything. There are many variables that should be filled. With a season opening, there’s an excitement to welcome people back, and in closing, we send them off into summer vacation. We also have our operas that we chose to do — and all the music we present is music of a very high quality.

Speaking of opera, it was a shame that Opera Pacific closed in 2008, but you’ve been taking up the slack a bit with your opera initiative, “Symphonic Voices,” having included concert productions of such works as Madame Butterfly, Aida, and The Magic Flute.

Our opera initiative is already a decade old, with recent performances of Otello. It was not a happy moment in anyone’s life in Orange County when the company [folded]. Having been the music director of two opera houses in Germany, I thought it would be good if I could help and replant opera in Orange County. There was a strong support for it, and they continue to be some of our most artistic initiatives. Next year we’re doing Rigoletto.

You’re also committed to the development and performance of new works by composers you’ve commissioned for recordings, such as Tobias Picker, James Newton Howard, and pianist/composer Conrad Tao. Why is this important to you?

[Mstislav] Rostropovich commissioned so many works for cello, and he said that maybe one or two out of seven will have a life on the stage, a real, fruitful life, but “without those five or six, I wouldn’t have found that one special piece.” I think it’s important we have a working relationship with living composers. I learn so much working with composers I can talk to and ask questions [of], and it [helps] with the process of a conductor interpreting music. It’s always been an important part of my life, and we’re commissioning works as we speak.

You’re also music director of the National Symphony Orchestra of Costa Rica. How many weeks are you there, and what is that like?

We play at the National Theater, [and] it’s the kind of theater you would see in Milan, [or] the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, or in Mexico City. There are parquet floors and chandeliers hanging in the entrance. It was built from 1891 to 1897, and it’s the most visited building in Costa Rica. I was just there last week.

After the pandemic, people are craving to get back, [and] we had two sold-out houses. These are exciting concerts and I’m going back after Mahler’s Fourth. It’s a full-time orchestra; the musicians and artistic initiatives are funded by the government, and everyone who plays in the orchestra is a government employee. I’m a government employee. The Costa Rican president in the 1940s disbanded its military, with the idea that money would be funded towards arts and education. That remains to this day.

Artistically, there are high spirits and high aspirations. We just had an election. [Rodrigo] Chaves Robles is our new president, and there’s a lot of change going on. But I have high hopes that’s it’s going to be great. [As for performances], I do half of the season, which is five to six concerts a year of the classics, and like all music directors, I create programs, oversee the repertory, the artists, and the administrative [duties], as well as do one or two weeks of recordings and outreach.

Finally, what makes for good chemistry between an orchestra and conductor?

Honesty of purpose — why you’re there and not somebody else — and trust. These kinds of things are crucial. It’s no different than between people. If you’re honest about why you’re there and you’re doing it to be there for the musicians and have them be there for the community and enrich lives, you have a chance of having a loyal and long relationship.