Sometimes you don’t have to wait long for destiny to place you. After he had graduated from studies with Helmut Rilling at the International Bach Academy in Stuttgart 29 years ago, Minnesota native Craig Hella Johnson (whose middle name is of Norwegian origin and not a colloquial Californian adverb) was transmuted from student to teacher at the University of Texas. He took with him a dream of founding a choir which could recruit top-drawer singers from a distance, establish an identity, and then extend back into the wider world to tour and record.

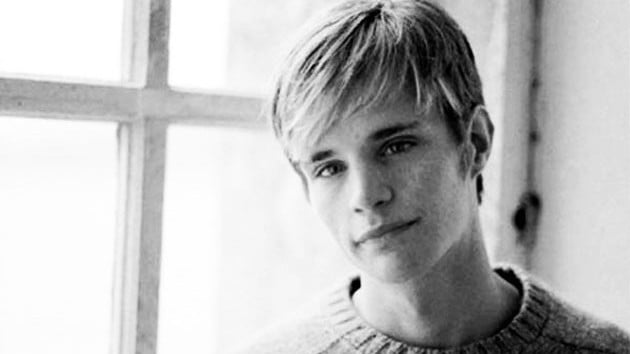

Twenty-five years ago, Johnson formed Conspirare, whose Latin name connotes breathing together. The ensemble has since garnered a Grammy for best choral performance, has recorded several seasonal albums, and is currently touring its Grammy-nominated Considering Matthew Shepard, with a score and libretto by Johnson. The piece, which involves male and female choristers, instrumentalists, and lighting and visual effects, memorializes the fatal homophobic incident of 1998, in which the title youth, a student at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, was tied to a fence, beaten, and left to die. SFCV spoke with Johnson from his Austin home, in the week before Conspirare’s California junket.

***

I heard from my neighbors, Nancy Quinn and Tom Driscoll, that you’ll be doing a preview, on Wednesday of this week, of your Matthew Shepard show at their home, before taking it to Stanford’s Bing Concert Hall on Saturday.

Tom was on our board for several years, and they’ve come down to visit Austin regularly. We’ll have two of our singers at their place, and we’ll also talk about the piece and how it came about, and share a little bit about the singers who premiered it [in 2016] and how things were written specifically for them. Most of this cast were at the premiere.

Have you visited the Bay Area frequently?

We got to know Tom and Nancy first when Conspirare came out to do two summer workshops at Mills, about 12 years ago. But I’d lived in San Francisco for all of 1998 — I was music director of Chanticleer. And my partner, Philip, was in the East Bay for 18 years. He’s an architect, and we were in a long-distance relationship for four years.

Where were you when you learned about the tragedy in Laramie, and how did it hit you?

I was in San Francisco. We were about to have a Chanticleer rehearsal that morning at St. Gregory of Nyssa, on Potrero Hill. One of the singers I’d hired, a young countertenor from Missouri named Matt Alber, came to me before the rehearsal in tears, and shared with me what he’d just learned. He said to me, “His name was Matt!” Then he just broke down crying. Then when I left rehearsal that morning, it was all over the news. It’s incredibly rich and meaningful for me and for Matt that he is part of this composition and these performances in California.

With all the homophobic violence over the years, including here in San Francisco, how was this incident different?

There was something about the aspect of his [Shepard’s] ordinariness. A lot of people say, “he looked like me, I could have been that person.” And some of the visuals associated with the incident became iconic. The Shepards [Matt’s parents] do not hold up the story that their son was a martyr, but one cannot consider that image of Matt’s arms outstretched on that fence and not get a “cross” image.

How does the fence play into your show?

The piece is in three parts: There’s a Prologue, the central body of the work is called the Passion section, and the last part is called the Epilogue. Within the Passion section, the framework is built from Lesléa Newman’s “Fence Poems,” from her October Mourning [Penguin Random House]. She was in Laramie the moment this all hit. She’d been invited to speak to student groups, including the LGBTQ group on campus. The fence held [Matthew’s] body, and it was standing in the same place when thousands of people brought flowers. I use the fence in a pivotal place in my piece, where we leave the Passion story to invite the listener to meet at the fence and ask: Where do we go from here? With such confounding darkness in our world, with such unfathomable evil and cruelty, where are we to find a core of love?

So Wyoming is represented by the fence.

Yes, the story is deeply grounded in the American West and all the images we have of the West. There are a couple of Wyoming poets included, John Nesbitt and Sue Wallis. The wonderful poem by Wallis, “Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass” is the first big movement.

Did you visit Wyoming?

Yes, I visited Laramie, and a few of the singers have done that, and a co-writer of the lyrics, Michael Dennis Brown, spent time in Wyoming. The American West extends to the idea we have of maleness, from our film images of John Wayne and others, the strong cowboy. We ask what it is to be a man. I have the choir singing this beautiful text from [Rabindranath] Tagore, the Bengali poet, and it’s set in a chant-like form.

What’s male about it?

It’s just men who are singing it, tenors and basses, and it’s in a form that was only populated by men when Gregorian chant was in common use in the church. They’ve just sung this piece “We Are All Sons,” a Michael Dennis Brown text, where they’re asking about the challenges of being a man in the modern world: “If they could know for the moment what it is like to live in our bodies.” There’s a quartet that’s asking a difficult question: Am I like you? It’s a text I wrote, and it refers to Aaron [McKinney] and Russell [Henderson], the perpetrators of this murder, two friends. In researching all of this, there was an extraordinary absence of these two in the story. It’s very “naked,” sort of Arvo Pärt language, David Lang language, where there are lots of rests, a lot of silence. I didn’t want this to be an experience which was all black-and-white; what about the culture which created these two men?

So even though our public knowledge of Matthew Shepard has been based on journalism, your creation, like The Laramie Project, can go beyond journalism.

This is certainly not a reporting. What we do report is in very short, spoken narrations.

Likewise, this is not your run-of-the-mill oratorio.

I’m glad you mentioned oratorios, because my whole life has been devoted to choral music, and I’m dedicated to these large-form stories. We think of this as a hybrid piece: Is it an oratorio, a choral work, an opera, musical theater?

Or all of the above.

Exactly. We’re always asking at Conspirare, how can we continue to explore with the choral medium. But within our culture, there’s been a backing away from the creation of new works that are in long form. Many years ago, when the iPod Shuffle came out, I thought it was glorious that so many people had these diverse listening lists. But it became a way where we only heard things in two- or three- or four-minute bits. Shortened attention span. We’ve noticed, though, that audiences can experience satisfaction in this, that [they] have time to contemplate things.

Are you bringing in new audiences?

I wanted it to be something that new listeners, and nonclassical listeners, could gain access to, with directness. I’d like to be able to reach people from my hometown in northern Minnesota, if we brought it there. And I wanted to address the stylistic diversity that we enjoy today, musically.

You’ve said some about the piece’s diversity, please say more.

Where there’s stylistic diversity, there’s an opportunity to have entry points for listeners. We have a blues kind of song, a plainsong chant, choral polyphony, and a simple Indie folk song. And in the last movement, there’s a Bach-like chorale, with Gospel kind of singing.

Is the touring ensemble for Considering Matthew Shepard a scaled-down version of Conspirare?

There’ll be 30 singers, women and men. And a chamber ensemble: piano, a double bass, violin, cello, viola, clarinet, percussion, and acoustic and electric guitars. I conduct from the piano.

What about the diversity of your audiences?

One of the most satisfying parts of the touring experience is the robustness of the response. There have been a few places where it felt like it was more needed, as a piece of art that can be a catalyst for conversations that need to take place: a couple of universities in Mississippi, and a university in the Midwest, where it felt like the student groups and support organizations were benefitting from the opportunity to have a piece of music around which they could plan forums and panel discussions.

Did it play in Laramie?

We performed it there last October. It was very emotional and powerful. Dennis Shepard, Matt’s father, joined us for that day. It was extraordinary to be singing that piece just down the road from where it had happened, under the Wyoming sky. Most of the piece is what the title suggests, “considering” Matt, and it’s not intended to wrap things up in a summary statement or wrap a bow around anything, because it’s too big for that.

You’ve kept the story alive since the piece was created, because it’s an affirmation, and an affirmation doesn’t come to an end with the applause, it has to keep going.

That’s beautifully said. We come together to contemplate a story in a way that we know stories and music can provoke and inspire us to inquire.

Conspirare performs Considering Matthew Shepard in Palo Alto for Stanford Live on Saturday, April 13 at 7:30 p.m.