A musical force for nearly four decades, three-time Grammy Award-winning violinist Hilary Hahn is taking a deep dive into the music of Johann Sebastian Bach when she returns to Walt Disney Concert Hall on March 15, this time for a solo recital. Featuring the composer’s Sonata No. 1 in G Minor and his Partitas Nos. 1 and 2 in B and D Minor, respectively, the program is one that Hahn has been performing since 2018, when she first stepped alone onto the stage of New York’s Alice Tully Hall.

Of that debut, The New York Times’ Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim wrote that “Hahn dispatched fast movements … with such fire and panache that the audience erupted in spontaneous (and graciously acknowledged) applause.” But virtuosity is nothing new for Hahn, who was born in 1979 in Lexington, Virginia, and began playing the violin before her fourth birthday, after her family moved to Baltimore and she was enrolled in the Suzuki program at the Peabody Institute. At age 10, the prodigy was admitted to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, making her major debut with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra the following year. It’s no surprise, then, that Hahn also completed Curtis’s university requirements at 16.

Currently artist-in-residence at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra — that organization’s first — and at London’s Wigmore Hall, Hahn has also championed works by a range of contemporary composers. Recent commissions include Michael Abels’s Isolation Variation and Lera Auerbach’s Sonata No. 4 (“Fractured Dreams”). To revitalize the encore genre, Hahn’s Grammy-winning multiyear commissioning project, In 27 Pieces: The Hilary Hahn Encores, included works by, among others, Jennifer Higdon and Nico Muhly. Then, in 2019, Hahn released a book of sheet music featuring her own fingerings and bowings, as well as performance notes, for each of the works.

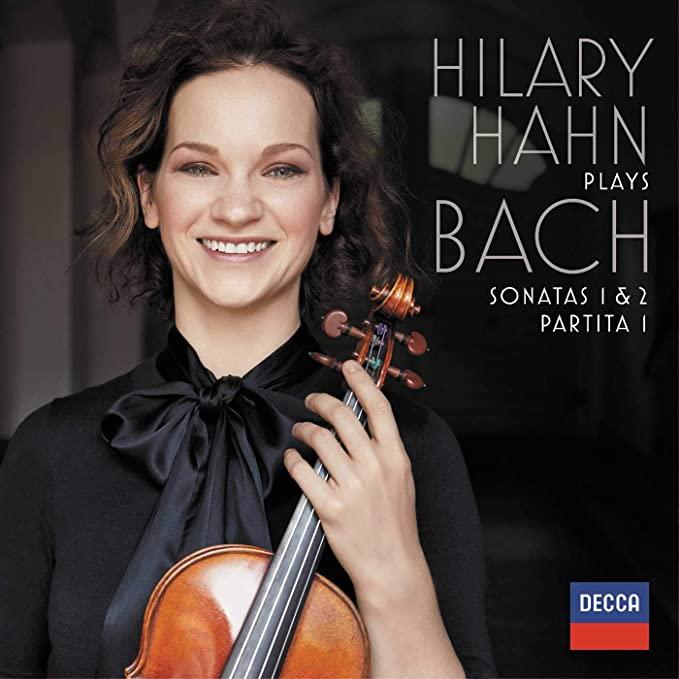

Based in Massachusetts, Hahn, who performs on an 1865 Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume violin, has also garnered numerous awards, including the 2021 Herbert von Karajan Award and Musical America’s 2023 Artist of the Year. In addition, she has released 22 feature albums, with her most recent recording, Eclipse, showcasing works by Antonín Dvořák, Alberto Ginastera, and Pablo de Sarasate.

SF Classical Voice had the opportunity to speak with Hahn by phone on topics including her love of Bach, how she manages to avoid burnout, and her Instagram-based initiative #100daysofpractice (@violincase), where she helps demystify the rigors and isolation of practicing.

You’re on tour now with your solo Bach program. Why do people love Bach so much?

I don’t know. You’d have to ask everyone individually. Everyone has a personal relationship to Bach, and a lot have stories about how important his music is to them, where they were when they heard it. This music connects with stories, it connects with the soul, it connects with the moment. I think there’s something he harnessed in his music that’s universal and inspired composers of his time.

Even now, it has radical elements that are super fascinating to work with. For me, I find it almost like a meditation and an exhalation at the same time. There’s always something interesting in the music that draws me in. Playing it, it’s endlessly malleable, endlessly interesting. Every concert, I play it differently. There are so many variables, and it’s like magic. To play it, it pulls you in, and there’s something always interesting to be doing with technique and, more than that, with the voicing.

On Jan. 1, you once again began #100daysofpractice on your Instagram account, which has nearly half a million followers and has helped turn the site into a kind of community-minded social celebration. What was the impetus for doing that?

This is actually the sixth time I’ve done it, and there are more than 500 [days of practice documented] in total. It’s a project I started maybe five years ago. I did it as a reference to a larger visual-art call where they were encouraging artists to show a work in progress, not just finished work. That was interesting to me as a musician. I thought, “What should I be doing for 100 days to join in?” and at that time it was more for me to be part of something that people were working on, creating.

I wasn’t thinking anyone else would care. I was just practicing — how boring! Then I started reading the comments and how transformative it was [for my followers] to see these practice posts. They hadn’t realized I would still be doing regular practicing. When I heard that people were saying it was vulnerable of me to put it up, I didn’t feel it was a risk or that I was vulnerable.

There’s actually a lot of negativity around practice. It’s hard to know what our relationship is supposed to be, and I was realizing that as I did the project. I did it twice in one year, and now I’m in a pattern. It’s not a New Year’s resolution thing, but it’s easy to keep track of starting on the first [day of the year]. People are interested in something to carry them through the middle of winter to spring, so it’s more like a seasonal connection than a New Year’s resolution. I also realized that people wanted to join in and they wanted to normalize practice — that there’s more to it than the working practice.

In one of your posts, you called violin playing a micro sport, and you’re on camera flexing what you referred to as the “Bach muscles.” Can you please elaborate on that?

I’ve been talking about it that way for a while. For me, the violin is very athletic. It feels like an Olympic gymnast’s tumbling routine. I think it’s interesting that it takes all these tiny muscles to play this instrument. It’s a beautiful instrument — you’re making art — but like someone doing a lot of photography, it’s hard on the body.

[Leonardo] da Vinci was doing his work on scaffolding. That’s got to have been challenging for the body. It’s demanding physical work, and then [you’re] creating something with your hands. It takes navigation of the physical space; it takes coordination, athleticism. We train our muscles in a certain way, [and this is] small-muscle gymnastics; the fingerboard is the tumbling mat.

You gave your first violin-alone recital in New York in 2018. Why did you wait so long? It certainly seems that it’s something you love.

I guess I really liked collaborating with other people. Also, playing a full solo recital was unknown [to me] physically. And I wasn’t interested in doing a solo alone onstage. It felt torturous; I was too much in my head. In order to convey everything as one performer, I needed to reach out hard to the audience, and they would need to get it from one instrument.

I had a lot of conversations in my head, and the first two concerts, I saw them as an interesting challenge that didn’t need to remain that way. I figured out my happy place by the third concert. I loved it. I changed my playing. I don’t have to do everything; I just have to play. That sounds simple, but you can only do what you can do.

If you’re in your head, you’re not authentically playing. The beautiful thing about a solo is I stay in every note for as long as it wants to exist. If it wants to take off, I take off. If it wants to take hold, I take hold. Music is so free and structured at the same time; I know it so well. I’ve been playing it for most of my life, and when I’m alone with it, I am free to play whatever occurs to me in the moment. It takes a lot of trust — not focus — because physically there’s an endurance aspect. But the psychological aspect is trust: in yourself, the audience, the hall.

Did you ever feel like quitting, or suffer from burnout, since you’ve been playing for most of your life?

Everyone has a different sort of arc for that, and for me, I definitely have had my days where I’m not sure why I’m doing something, or where I’m not absolutely convinced, or I’m burned out, or I don’t know whether what I’m doing in the music is coming across. And that can be exhausting.

But I just enjoy making music. I have to come to a peace with the status quo of the moment and then the next day reach a conclusion. Waiting a day and looking at what is actually going on and being patient helps a lot with burnout. Another thing is that music is a great way to connect with emotions and to clear things out of your system. If I’m feeling worn out, which is one form of burnout, I play lower energy on purpose.

I play into the emotions. I don’t try to force it, but playing what I’m actually feeling helps me process it and move forward to a different mindset. If you play into it, it’s very connected, and the audience will get what they need to hear, and you proceed through it. It’s a way of making something beautiful [out of] something that could be frustrating.

What are your criteria when you commission a work?

Working with a composer when I do solo work, I find that whatever I decide to do with the music — whether I follow the score precisely or their request precisely — there’s no one else to have a different way of playing it. I have to play it in a way that’s organized for me because the audience doesn’t know the music yet and I’m still learning its identity. I want to get inside [the composer’s] concept, and I do my best to do what they’re asking, and if I can’t, I do my best to bring it across in a unique way.

A duo is different because I’m coordinating with my colleagues and we’re figuring it out together, with the advice of the composer. If it’s orchestral, you’re doing the best with the time you have. In an orchestral [work], the concept is resting with the soloist and conductor, so in rehearsal, you use time to get things as polished as possible within the orchestra. You want to get the voicing clear [and] make sure the tempi are reliable.

You get two full rehearsals, if you’re lucky, for a premiere for a concerto, so there’s a bit of triage that happens: What is it that we need to work on right now, and how can we get it so it’s not a lot of navel-gazing? I have to walk in knowing my direction [and] knowing what I want to do so there’s something to start with.

Where do you see yourself in the next five to 10 years?

I don’t know. I tend more to stay on a trajectory than have a set goal. I know how I want things to feel like, and I make a lot of decisions on direction every day. But it’s hard to control life, so I leave a buffer for that as well.

Every day I try to accomplish something positive in the music world or with music — just a little something. The arts are important for the quality of life, self-expression, and the emotional documentation of our time, for history, for telling a story. They’re really good for the soul, [and] I always try to contribute to the mix every day as best I can.