A month ago, the School of the Getdown hosted its annual Youth Arts Camp at Geoffrey’s Inner Circle in Oakland’s Black Arts Movement Business District. The kids got to learn and make lots of music, as well as listen to words of wisdom from the school’s founder, The Dynamic Miss Faye Carol.

“I always tell my students, ‘You do not have the right to be bored,’” says the jazz vocalist. She and her musical director and pianist Joe Warner spoke with SF Classical Voice while planning their return to Geoffrey’s for an August-long series billed as Faye & The Folks. This will be the pair’s third month of Sundays at the venue after previous engagements in March 2020 (interrupted by the pandemic) and February 2022.

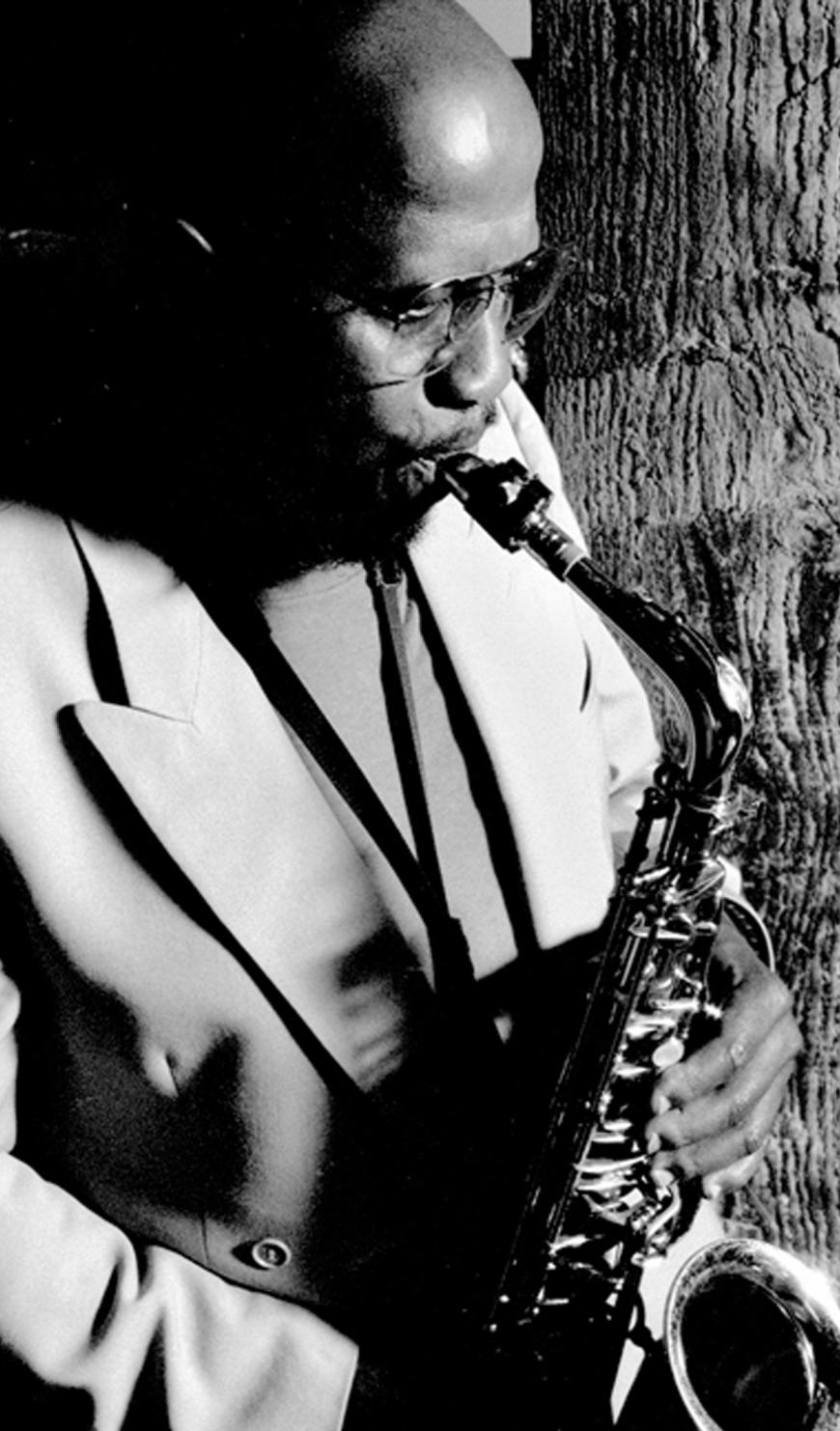

And as in those series, “we’re going to be doing music of every description,” Carol promises, “and we’re going to have ourselves one hell of a good time.” Although moving among several musical genres, the series focuses on performers from Oakland. The second Sunday (Aug. 13) will offer a reunion — for Carol, Warner, and Bay Area jazz fans — with 90-year-old saxophonist John Handy. (Warner is 31, and Carol accounts for her vintage as “timeless.”)

Carol recalls being introduced to Handy in the early ’70s, when she was “doing mostly funk stuff” and was married to the late music educator Jim Gamble. Warner had lost track of Handy since gigging with him at the erstwhile Yoshi’s San Francisco about a decade ago. He was delighted to hear the saxophonist on KCSM’s broadcast of the Jazz on the Hill festival in early June, where Handy was presented with the Jazz Icon Award and sat in with the Akira Tana Quartet.

“John just sounded so good,” Warner enthuses. “He’ll give you that old-school authentic thing, and when he plays a ballad, it’s hard to replicate if you don’t come from that era. But he’s also very modern and can be abstract in his thinking. A lot of his music is very free and open and forward-thinking.”

Handy spoke with SF Classical Voice in the quiet, woodsy Sequoyah neighborhood of Oakland, where he lives with his third wife, Del Anderson, an administrator who served as the first Black and first female chancellor of City College of San Francisco. The pair met at a political convention in Sacramento and discovered their shared affection for activism, good food, and jazz.

Handy first arrived in Oakland as a 15-year-old, transferring to the city’s McClymonds High School after attending St. Peter’s Academy in his native Dallas. By that point, he’d already learned to play the clarinet and had been declared Dallas’s featherweight boxing champion, despite being blind in one eye and having dislocated his right thumb in a fight. He’d also acquired a love of jazz, falling asleep to the sound of Charlie Parker while his stepfather hosted parties to promote his illegal liquor business.

Schoolmates at McClymonds included members of the musical Escovedo family and violinist and future bandmate Michael White. Handy encountered another schoolmate, future star athlete Bill Russell, at a nearby rec center and challenged him to a basketball tourney. “I won the first game — of 15,” Handy chuckles.

He discovered the school also boasted an excellent band, and with a reed, mouthpiece, and horn loaned to him by fellow students and the instructor, Handy quickly learned to play the alto sax and scored a gig within a week. “That was $5, and that became my way of making money,” he says. He played in blues bands, and “most of my gigs were in the East Bay. I was 17 before I went to San Francisco and discovered Bop City,” a major midcentury jazz destination in the Western Addition.

“I taught myself how to read music, and if I heard something on the radio, I could play it,” says Handy. “When Louis Jordan was popular, I learned some of his solos.” Earl Bostic’s haunting upper register on alto was a major influence. While still a teenager, Handy jammed at Bop City, sat in there with visiting members of Duke Ellington’s band, and joined Gerald Wilson’s band. He also enrolled at San Francisco State College, and at age 20, he made his first recording, with guitarist Lowell Fulson. Soon after, he was drafted and posted to Korea, where the war had just ended. He spent two years in the military, with his last posting placing him conveniently at San Francisco’s Presidio.

“Then I ended up getting married, and we had a son, John Handy IV, who’s a drummer.” The young saxophonist returned to SF State, where jazz was not yet part of the music department’s curriculum, although Handy and other jazz-minded students could perform in ensembles. Outside the campus, “some of the best people in jazz would come to Bop City. But by the mid-’50s, they were letting people in that would ruin it, because they didn’t know crap about music and didn’t care to know.” He was particularly displeased with singers. Handy, caught up with raising his son, turned down an invitation from a visiting Charles Mingus in 1957 to join his band, whose members “complained a lot about Charles, but not in his company. They said he was a real asshole.”

After delays imposed by an unsympathetic SF State professor, Handy received his degree in 1958 and relocated to New York, where he joined Mingus and secured his first recording under his own name, on Roulette Records, through the efforts of his wife, who was also his manager. Vibraphonist Milt Jackson (of the Modern Jazz Quartet), who had befriended the couple, offered them a furnished apartment close to Harlem. “Most of my gigs were with Charles, but I played the whole summer of ’59 with Randy Weston at the Five Spot,” says Handy. “Though Charles and Randy were both mavericks, Randy was more positive.” He hums the melody of Weston’s “Hi-Fly,” said to have been inspired by the pianist-songwriter’s height of 6 feet 8 inches, more than a foot taller than Handy.

“We played with Randy six nights a week. That’s where my exposure came. One of the characters who came in to the Five Spot was the Baroness [Kathleen Annie Pannonica de Koenigswarter]; she came in with Thelonious Monk almost every night.” Monk is reputed to have paid Handy an elliptical compliment, and Handy later opened for Monk at the Jazz Gallery.

Handy returned to San Francisco and “got very active in civil rights in the early ’60s. I couldn’t sit back, with all I’d gone through, and let somebody fight for me without trying to help my own cause.” Black Americans (among them Giants player Willie Mays) were enduring housing discrimination, and Handy was arrested during a protest. “Willie Brown was one of the lawyers who got us out.” To raise money for the cause, Handy formed the Freedom Band with a pair of young tenor players, Mel Martin and Noel Jewkes, and trumpeter Eddie Henderson.

The local jazz scene was capably covered by San Francisco Chronicle columnist and critic Ralph Gleason, who showed up at one of Handy’s gigs at the popular, progressive Both/And Club on Divisadero Street. “I’d had the flu, but I told the guys, ‘Let’s wake up!’ And Ralph wrote about it, and the club was packed every night.” It was at the Both/And that Handy first heard Faye Carol. He doesn’t recall racism in venues or in the musicians’ union. “You don’t see that in jazz.” Divorced from his first wife, Handy married a woman he’d met at the Five Spot and bought a home on Baker Street.

The Monterey Jazz Festival, co-founded by Gleason and publisher and broadcaster Jimmy Lyons, booked Handy’s quintet in 1965. The live recording of this gig, released by Columbia the following year, earned Handy two Grammy nominations.

In 1968, he returned to SF State as faculty, “teaching both Black studies and white studies” on music and history. Of the classical faculty, Handy says, “I know they were jealous of me because I could do what they did but they couldn’t do what I did.” He was commissioned to compose a Concerto for Jazz Soloist and Orchestra, which he performed with the San Francisco Symphony in 1970. Handy also taught at UC Berkeley, Stanford, and City College of San Francisco.

Through former classmates at SF State, Handy was introduced to sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar, who shared with him two private lessons in North Indian classical modes. “And I understood, because when I went to St. Peter’s, we sang Gregorian modal music. And African Americans are very modal. Later, I recorded with Ravi in India.

“Then I got a call to play with [sarodist] Ali Akbar Khan. I went to his house in Marin County, and it was like I’d been playing with him all my life. I booked several concerts with him and paid him half of the ticket sales, though I realized that Indian musicians don’t do what we do. They don’t change keys and can’t play jazz.” Handy and Khan recorded two albums together, and Handy retains a tabla, gifted to him by Zakir Hussain (who played on the 1975 MPS recording Karuna Supreme), and a tanpura.

The title track on the 1976 ABC/Impulse album Hard Work was arguably Handy’s biggest hit, placing on the Billboard charts and ending up in numerous jukeboxes worldwide. Its propulsive brassy funk and repeated chant qualified as a crossover hit, rare in jazz. In the 1980s, Handy joined the Bebop and Beyond ensemble, a host of Bay Area-based players honoring the bebop legacy in performance and recording, with trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie even joining them for his own tribute. Later in the ’80s, John Handy With Class featured the saxophonist with three female violinist-singers, performing and recording in formal dress.

In his hillside home, Handy has kept up his music-making, despite a mild stroke a couple of years ago. “Before Jazz on the Hill, I hadn´t heard anything from John lately, so I was so happy when he said he’d do our [Aug. 13] show,” says Faye Carol. “I’ve been trying to get the opportunity to work with John since that Yoshi’s gig,” adds Joe Warner. “And we have a great band for him, with Tarus Mateen on bass, who plays with [pianist] Jason Moran, and Jaz Sawyer, a great drummer I worked with when he was living up here, who’s been in Southern California.”

The first Geoffrey’s gig next month, on Aug. 6, is billed as “Soul Explosion” and features soul singer Derick Hughes, along with alto player Eddie M, drummer Dante Roberson, and bassist Marcus Phillips. MJ’s Brass Boppers, appearing Aug. 20, are described by Warner as “a New Orleans-style second line band, a lot of fun. We had them at Geoffrey’s last year, and they were a crowd favorite.” The “Funky Latin Getdown” on Aug. 27 is also a repeat offering, showcasing percussionist Jesus Diaz and a band with a three-horn front line, including tenor titan Craig Handy (no relation to John).

Carol and Warner, who have collaborated for 11 years, have maintained a remarkably high post-pandemic profile at various Bay Area venues. They recently extended their act to the East Coast, with appearances at Mezzrow in New York and Keystone Korner in Baltimore, recruiting several of the musicians they’ve featured at Geoffrey’s. Carol attributes her success “first, to my tenacity for just hanging in there. And to have had my husband, Jim Gamble, give me a whole lot of knowledge about Black music so I could make my living within it and teach it. And to have my daughter, Kito Gamble, to be able to perform with and build arrangements. Then to meet Joe Warner, who is a tenacious warrior who never stops working. And to get help from the state and the city for our Sundays.” The City of Oakland sponsors the series.

Warner shares credit for the series’ success with Geoffrey Pete, proprietor of the venue. “He really believes in the culture and the music and wants what’s best for the artists,” Warner says. “A lot of other places, you’re performing, and people enjoy the performance because the music is great. But at Geoffrey’s, you’re giving people music that speaks to them and feeds their souls. And it’s a beautiful venue aesthetically, with wood floors, columns, and pictures of Black history.” Pete is currently appealing a permit granted for a nearby residential tower that would overshadow his building and make parking difficult.

“We need this relevant place that’s vital to the community of Oakland,” adds Carol. “Entertainment is not a luxury, it’s an essential thing. You can come down to 14th Street and have a good time, get some good fried chicken and a martini, and then turn around and toast your people. And listen to great music.” For more information, go to the Geoffrey’s Inner Circle website.