It’s mere coincidence that composer Anthony Davis received word of winning the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Music less than a month before protests over the killing of Breonna Taylor and then the shocking video of the murder of George Floyd. It is, however, no coincidence that the opera he won the prize for, The Central Park Five, was about bias in American law enforcement, and not just at the police level.

Davis has always been political, but his work in opera is deeply connected to a sense of epic stories, tragic stories with a sense of inevitability to them. He won the Pulitzer precisely because he digs much deeper than just a political take, notwithstanding the villain of the piece, a certain real-estate developer with a talent for attracting media attention. The committee noted that the opera “transforms a notorious example of contemporary injustice into something empathetic and hopeful.”

Despite his breadth of musical understanding and his philosophical soul, Davis’s music is powerfully present, pushing you to feel emotions rather than to sit back and contemplate the bigger picture. His compositions have big melodies and dramatic arcs immediately identifiable to listeners of Beethoven or Duke Ellington or Alban Berg.

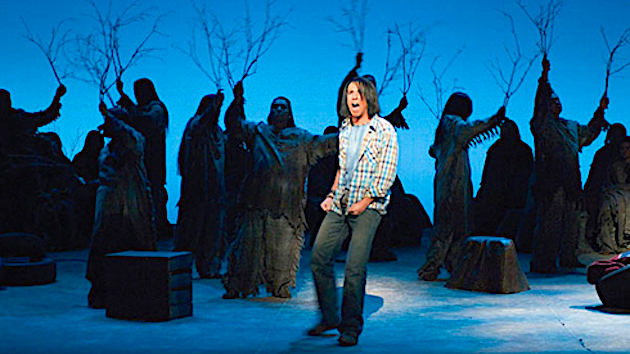

Awards don’t help us quantify these qualities, but for a composer who burst onto the operatic scene so spectacularly with X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X at the New York City Opera in 1986, it’s an acknowledgement of his eminence in a world, classical music, that has usually struggled to deal honestly with Black musicians and Black experience.

Are things starting to change? Yuval Sharon has committed Michigan Opera Theater to a new production of a slightly revised and condensed X in 2022. New York City Opera has slated The Central Park Five for a 2021–2022 production. The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra has, this past November, successfully presented his clarinet concerto You Have the Right to Remain Silent (2007), with Anthony McGill as soloist and Louis Langree on the podium.

And as Davis turns 70 this year, he continues composing. He and his cousin, poet and historian Thulani Davis, have started work on an opera, Greenwood, 1921, about the Tulsa race riots. “Hopefully it will be a commission,” he says. “I think that will happen. But you know it doesn’t make any sense for me to sit around and not do anything. So in the dry periods I was working on Lear on the Second Floor [2013] and Lilith [2009] and other operas that I did on my own. I love composing, so why should I deprive myself? Just because I’m not getting a paycheck at the right time? You have to do it to keep the work going.”

It’s getting a little easier for classical organizations to present his work, also. A typical Davis composition, like You Have the Right to Remain Silent, will have some jazz-like improvisation in it, not to mention stylistic fluidity.

“Cincinnati was very easy,” Davis reports. “I didn’t really have any issues, and the conductor [Louis Langree] was fantastic. Anthony [McGill] hadn’t done that much improvisation before and I worked with him and he really rose to the occasion. And great musicians are like that, open to trying new things. I remember when I was first doing orchestral music in the early ’80s, it was a little bit problematic, and with European orchestras as well. But you know, I did a piece for the New World Symphony [a professional training orchestra in Miami] and I asked the string players how many of them improvised and half of them raised their hands. So it’s a different world. That was the signal to me that there was a change and that orchestras can be more open to these ideas. Cincinnati was very successful with what they did, and I think the piece has the potential to be done by different orchestras.”

As SFCV has been reporting, the enforced pandemic break has made it possible, and necessary, for arts organizations to examine what they do, how they present it to the public, and who they include in the public. That may be working to Davis’s advantage, along with other musicians of color. “I think those are important issues that every company needs to explore, particularly with all the race issues brought up by George Floyd, etc. And actually, this enforced break allows them to really view and think about what the role of opera has been and whether it’s going to be on the side of change and progress or on the side of trying to reinforce the cultural apartheid that exists in our country.”

Davis, though he is no revolutionary, is still a breakthrough composer. He has had to be, since few musicians before him had the opportunity to lay out the history of Black music in America in major works for top-level classical organizations. The epic is a part of his music not merely because of the Wagnerian inspiration that started him down the path of making opera, but also because his operas and symphonic works enact a meeting of Black musical traditions and European classical music.

Trained in jazz and South Asian musics as well as classical piano, Davis emerged in a postcolonial world in which many Black musicians, preeminently members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, were trying to imagine a music that moved beyond genres and racial categories, which they, as Black musicians, rightly saw as limiting. Davis’s music does that, honoring Black history while creating a musical fusion that includes elements from many traditions.

His fusion rejects master narratives. He is participating in a project that George Lewis described as exploring “what it means — and could mean — to be American, helping to foster a creolized, cosmopolitan new music for the 21st century.” In a New York Times profile from 1992, Davis said, “I knew I could never be accepted as a straight-ahead jazz musician, nor would I accept myself as that. I would never be accepted as a minimalist. I wouldn’t be a “downtown” composer. Because I find all orthodoxies, all doctrines, to be ultimately banal.” The intriguing point about Anthony Davis is that he managed to do those necessary formal experiments and accommodate his political orientation in his works while also bringing a classical audience along with him.

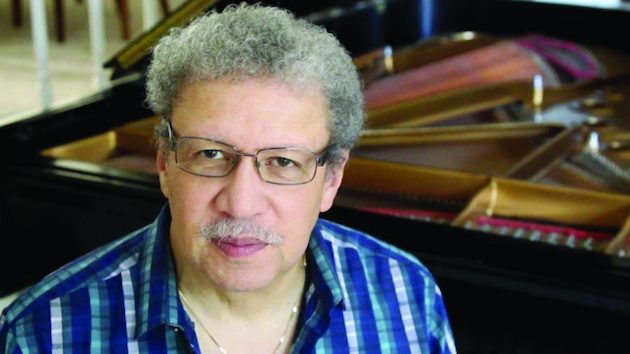

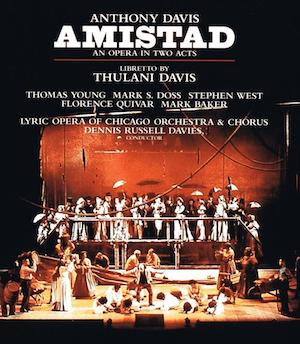

Davis has always ignored barriers, and he has the background and perspective to do it. He was born in 1951 in Paterson, New Jersey. His father, Charles Twichell Davis, was an influential academic, the first Black professor of English at Princeton University, and was later the first chair of the Yale African American Studies program, where he mentored, among others, Henry Louis Gates Jr. Gates became a friend of Anthony as well, and the ideas in his breakthrough book, The Signifying Monkey (1988) have influenced Davis’s thinking as far back as his 1983 recording Hemispheres, an album-length suite that includes two movements titled after the Esu-Elegbara trickster figure who figures prominently in Gates’s book. The character is also included in a scene from the 1997 opera Amistad, and in the Amistad Symphony (La Jolla Symphony, 2009).

In conversation, Anthony Davis has an exceptional command of Black music, especially jazz, which also shows up in his compositions, especially operas where he quotes everything from an early Ellington classic to rap (although in Central Park Five, he used the speech rhythms of rap and funk riffs that are quoted in rap rather than hip-hop music itself.) In spite of his often-professed love for the formal innovations of Duke Ellington, however, it was Thelonious Monk who sparked his developing compositional interests.

“When I first heard his music,” Davis informed me, “what intrigued me was the seamlessness between his compositional ideas and his playing. Prior to listening to Monk, I listened to Art Tatum and other great pianists — Errol Garner — but they weren’t really composers, not the way Monk was. But that language that he developed was so unique and so personal and it pervaded everything. And that really excited me, and also how he approached dissonance and harmony and rhythm.” From Monk, Davis took the idea that jazz could be both rigorously composed and improvised by turns. It’s the fusing of the ideas of European counterpoint with the improvisation at the heart of jazz that showed Davis his path. “When you play Monk, you have to use what he did — his voicings, — it’s about counterpoint and not just about changes.”

He headed to Yale as an undergraduate, majoring in philosophy, but still playing jazz as a pianist, and taking courses in South Indian music and gamelan at Wesleyan University. Graduating in 1975, in music, he went to New York City, embraced the free-jazz movement, and was taken under the wing of several members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM).

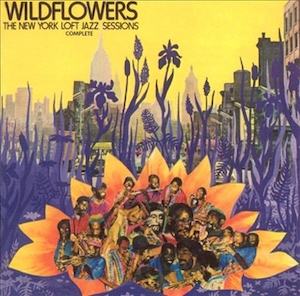

“I met Anthony Braxton [b. 1945] in the ’70s through Wadada Leo Smith [b. 1941],” he remembers. “My friend George Lewis started playing with him and the first time was a Wildflowers recording and I was involved with that. I did a recording with Wadada for that at Studio Rivbea, which was Sam Rivers’s place [a free-jazz loft, more than a recording studio] and so I went there to hear George and I saw Braxton on the street, and he said, “Oh, Anthony, would you like to play on the session?” I said, “sure,” so he sang me the tune in the street, and we played it. That was it. Get up there and hit. And I played on another album with Braxton later.

“They were influential because they were a little older than me and they opened doors for me and George and my generation of musicians. They were writing for orchestra, thinking about music that way that didn’t fit into any categories. And that was interesting to me — to not accept the limitations of so-called ‘jazz.’” You can hear Davis on piano with the Wadada Leo Smith Golden Quartet on a PBS Vermont telecast from 2016.

Settling in New York, in 1977, Davis put out several jazz recordings on his own, and founded his own free-jazz group, Episteme, where he worked out his own stylistic collisions that included gamelan influence on their eponymous debut album (1981) and his Wayang pieces like Under the Double Moon (the instrumental piece, not the opera). In an often-told story, his brother Christopher suggested that he write a musical based on Malcolm X’s biography, and they and Thulani Davis ended up creating the opera X, as part of the American Musical Theater Festival in Philadelphia, which gave a performance in October 1985. It was a sensation at the New York City Opera in its official premiere but never returned, apparently because the company was worried that its regulars had stayed away from the premiere. X includes a 14-member improvisatory group within the orchestra, as well as extensive references to Black music seamlessly woven into the fabric. It’s an astonishing first opera.

There’s a political side to X, in which a revolutionary character, finally reaching self-enlightenment is too dangerous to let live. But Davis also sees what drew him to the opera in the first place as having to do with Greek tragedy.

“He’s the Cassandra character. Someone who tells the truth all the time but no one’s going to let you hear them. That’s from Nietzsche: I got into opera from The Birth of Tragedy [From the Spirit of Music, the philosopher’s first big book, which takes up Wagner and Wagnerian themes.] That’s something I think about in Greek tragedy as well. In tragedy there’s this momentum and that’s what’s captured by the rhythmic aspect of it; that you’re hurled into the future. In the opera, Malcolm X is being pushed and the audience is being pushed too. I want the audience to feel something emotional in the music. I’ve always loved Nietzsche because Nietzsche talks about music and the spirit of revolution and I liked the radical aspect of that and how music can be freeing and create an experience that is cathartic.

“I want the music to compel the character, make them do the action. That’s why it’s even different from musicals, because I look at the action of the opera as embedded in the music, too. It’s part of the action.”

Unlike Wagner, Davis uses rhythmic cells to create form and “plant seeds” in the minds of the audience. “Let’s say if I have a pattern of 25 beats against 20, there’s a point at which the patterns come together and at that point dramatic change can happen. I call them “nodes.” And that point musical and dramatic change can happen. In place of [Wagner’s] harmonic cadences there are rhythmic cadences. That’s the idea.”

Davis got his first academic appointment (at Yale) at the same time as he began his second opera, Under the Double Moon (1989, Opera Theater of St. Louis) to a libretto by his first wife, science-fiction author Deborah Atherton. It has connections to his album of the same name; he calls it his “wayang opera.” Wayang is traditional Javanese puppet theater accompanied by a gamelan orchestra.

“I was excited because X was very eclectic. There was a whole range of things in terms of style and drawing upon my experience in jazz and all kinds of stuff. In Under the Double Moon, I wrote a very specific language that was very much about creating a different world. And it’s all based on my wayang music, and it’s basically this liminal space inspired by the gamelan music and South Indian music and Japanese shakuhachi [flute] music, but very much its own thing.”

Amistad was written on commission from Chicago Lyric Opera and premiered in 1997, and while some critics panned it, it remains one of the composer’s most powerful pieces of music, and a 2008 revision was successfully produced at the Spoleto Festival. By that time, he had followed George Lewis to UC San Diego, where he remains on the composition faculty.

The opera that followed, Wakonda’s Dream, for Opera Omaha (2007, libretto by Yusef Komunyakaa), was another big change. The company had asked him for an opera about the trial of Standing Bear, but having just done a trial opera, he wanted a different way in.

“I went to a powwow in Niobrara Nebraska, near the border with South Dakota. There’s a Ponca reservation there. And so I visited the Ponca and went to the powwow, and that was transformative. My whole concept of the opera came out of that. At the powwow, I saw this child who was dancing with black feathers. I spoke to the mother of the child, later, and she said he has black feathers because he had foresight, he could see the future. He heard voices and spoke to people in the past and I thought that was incredible. So we decided to do it from the perspective of a child who hears and speaks to Standing Bear. And it’s more about Native life today and that they’re haunted by Standing Bear and the Pyrrhic victory that the court case really was because it gave him the right to live where he wanted, back in Niobrara, but only as an individual, not as a tribe.”

The musical inspiration included a Ponca honor song that Davis transcribed, electronically processed coyote calls, and Native hip-hop. “I had a Native American student at the time at UCSD and he gave me all kinds of Native music to listen to. He was doing his dissertation on Native American hip-hop, so I got into that.” The hip-hop number written by Davis and Komunyakaa, “begins the downward spiral of Act II,” as the scholar Ruth Sara Longobardi puts it, noting that, in the original production, the song is vocalized by Native American dancers, not singers, giving it a rough quality.

“I decided to open the whole opera with a vision quest. And so I used natural sounds: My friend Liz Philips walked in the woods with a helmet with two microphones so we recorded that and used that as part of the soundscape so that as the audience came in they were, in effect they were in the woods. The title is [refers to] Wakonda, [which] is part of the creation myth; the idea is that whatever happens in the world is Wakonda’s dream, he created the world. So in a way, Wakonda’s dream is fate. We’re all part of Wakonda’s dream.”

The political is always there in Davis’s work, but so is this sense of quest, of radical openness that reexamines opera’s form every time. He’s also constantly moving back and forth between history and the now, just like the most traditional of classical composers.

“When I was doing Amistad,” he says, “I was very interested in hermeneutics and thinking about the trickster figure as Hermes, and the idea of the playfulness of the trickster with words, knowing how to speak truth to power and at the same time as a mediator between gods and men. And also the idea that he’s not really ethical. He won’t tell you the right way to go; he’s the guy at the crossroads. So the idea of introducing playfulness into how we look at the past and also as we examine history; it’s a creative act, how we imagine the past.

“I like to be able to imagine my freedom, the idea that I can create building on different foundations — Ellington, Strayhorn, Mingus, and the jazz tradition and also building on the operatic tradition from Britten, Schoenberg, back to Puccini, Wagner, and everything. Finding that space between all these things in which I’ll allow myself to engage freely as I see what works for the dramatic situation and what I want to create, that’s always exciting to me.

“Monk was in my dream last night. That’s something that happens all the time, that communication. I met Duke Ellington when I was about 19 years old. He came in for a reception and I had a huge afro at the time, like an Angela Davis afro, and I was across the whole room and he looked at me and pointed at me and said ‘You must be a musician.’ He just knew. He told me I was going to be a musician and that was it.

“I always feel that I’m in conversation with those people, too. It’s not a burden, it’s liberating. It frees you to have their courage, to make your own music. And hopefully that’s something that I can do for my students.”