Contemporary operas often have a hard time finding an audience, much less receiving additional performances after their premieres. Such was certainly the case with William Grant Still’s one-act gem Highway 1, USA, which premiered in 1963 but wasn’t mounted by a major opera company until June 2021, when Opera Theatre of Saint Louis produced an outdoor staging under pandemic distancing rules.

But Still’s operatic draught may be coming to an end as Los Angeles Opera presents Highway 1, USA in a double bill with Alexander Zemlinksy’s 1922 one-act The Dwarf, the latter seen at LA Opera in 2008. Six performances run Feb. 24 – March 17 at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, conducted by LAO Music Director James Conlon.

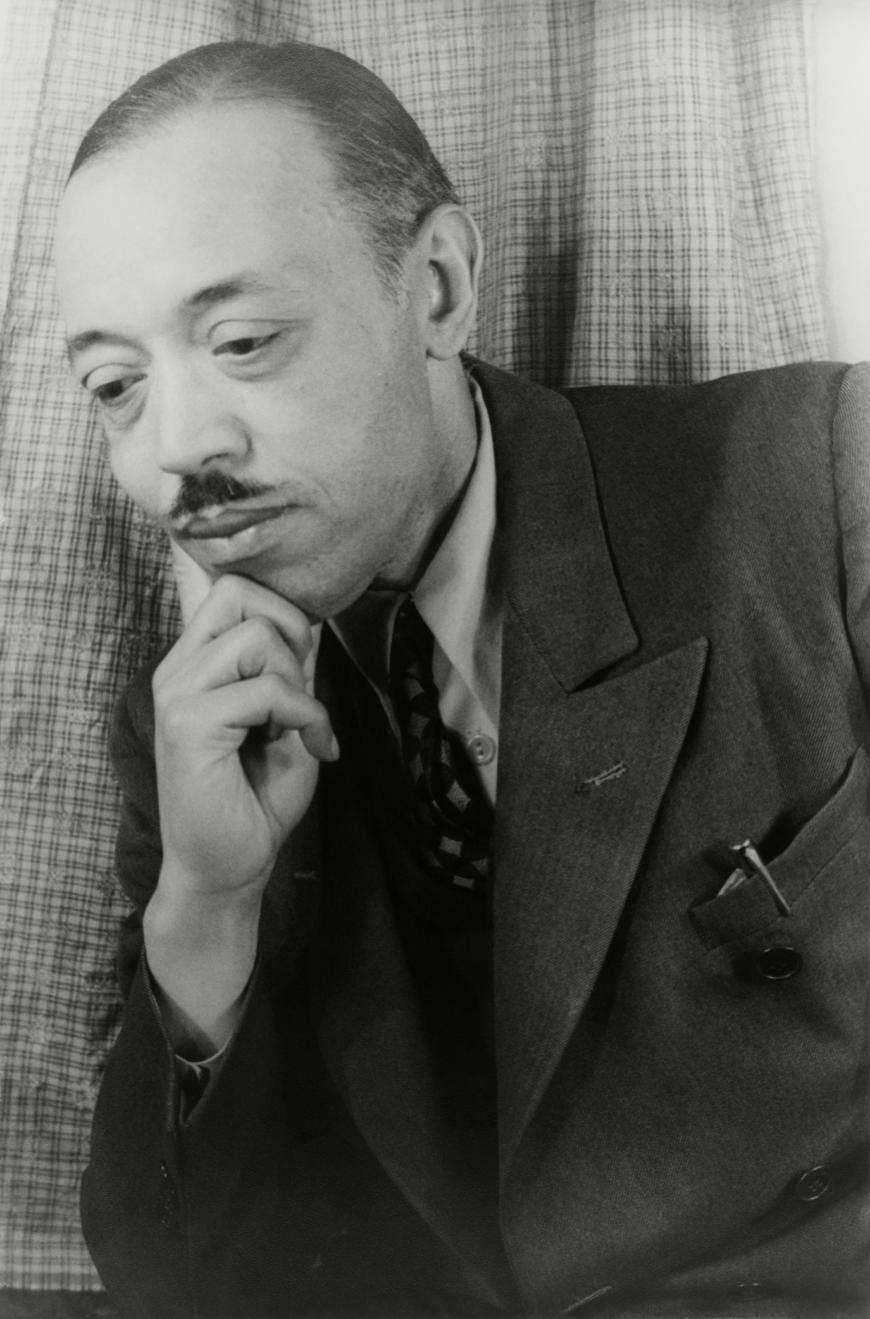

Once hailed as the “dean of African American composers,” Still, who died in 1978 at age 83, had been part of the Harlem Renaissance movement and was a trailblazing artist. His hugely popular Afro-American Symphony, which had its premiere in 1931 with the Rochester Philharmonic, successfully incorporated blues into orchestral music. (The Los Angeles Philharmonic performed it in 1940, while Leopold Stokowski toured the work with The Philadelphia Orchestra in 1936).

Still, who was born in Mississippi and briefly studied at Oberlin College, as well as being tutored in New York by the experimental composer Edgard Varèse, wrote in many genres, from numerous songs to ballet scores and orchestral pieces. But his nine operas, including the 1939 Troubled Island, with a libretto by Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes, struggled to gain traction.

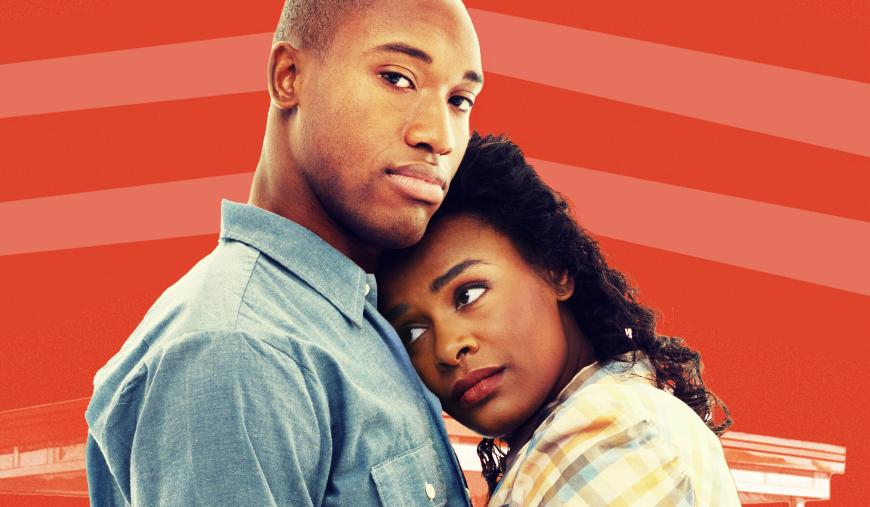

That same year, Still married his second wife, Verna Arvey, a distinguished concert pianist and journalist. One of her husband’s greatest champions, she also contributed to Hughes’s libretto, as well as wrote the texts for Still’s subsequent operas, including Highway 1, USA. The two-scene, one-hour work deals with familial expectations and responsibility and is basically a simple story: A married couple, Bob and Mary, run a gas station while supporting Bob’s younger brother, Nate, through college, honoring a request that had been made by the siblings’ mother on her deathbed. As Nate is about to graduate, hoping the financing will continue, Mary becomes distraught.

After making her LAO debut in 2022 directing Omar (Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels’s 2023 Pulitzer Prize-winning opera), Kaneza Schaal was tapped by LAO President and CEO Christopher Koelsch to direct Highway 1. She was excited to bring Still back to the spotlight, and although she hadn’t at that time heard the music to the opera, she understood Still, who had been steeped in classical music as a child, to be a “complicated musical thinker.”

Schaal explained: “He was involved with so many different communities of musical thought, from his being [musical director of] Black Swan Records [under its owner] Harry Pace to [arranging scores for] Hollywood films, let alone all of his classical training. What draws me to Still is that there is a vast musical lexicon under every note, and people tend to oversimplify how they look at his music.”

For her staging, the Brooklyn-based Schaal, who was a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow and received a Herb Alpert Award in Theatre that same year, said that the first question Conlon asked when they sat down for tea was “Where is the opera set?”

“I told him that I set it in Still’s imagination — that what he is dreaming is possible from when he first wrote Highway 1 to when he first heard it [performed] in the’60s. It lands us in a clean facade and the dark, dark underbelly of the ’50s.”

As part of her research, Schaal looked at artists from Still’s time, including painters James Rosenquist and Alma Thomas, “who,” the director pointed out, “thought about fracture and wholeness,” while the actual physical setting of the opera is a small 1940s-era apartment. “Because,” Schaal explained, “it represented an interesting moment in American history, a kind of pivot point. On one hand, there’s the American dream of hard work, meritocracy, the promise of the road and the West, and the kinds of independence that signified [success] for African Americans — indeed, for all Americans.

“On the other hand, there’s this other model of success, a new thing happening then. University educations become accessible for so many more people — Black people, GIs through the GI bill. There was this other order of aspiration. Verna Arvey and Still are thinking about this, which would eventually be the beginning of the end of the middle class.”

Still’s music is also, Schaal pointed out, “reaching to build a new world. When I first heard it, I got super lost in the strings. The sweeping strings would come through, and I lost sight of the opera and [felt like I was] in a ’50s film.

“Or a sitcom,” said Schaal, who has also worked in theater and film and has lectured at, among other institutions, Yale University and New York University. “I was speaking with friends about the 1940s, and there was the backdrop of war, then came the commercialism of the sitcom The Honeymooners [for example].

“The sitcom logic is the American dream, where we hold an aspirational world, [and] Still’s music sends us into the complexities of thought in everyone. I do not hear a condemnation of Nate in the music. [Instead] we’re invited to consider the competing dreams and different Americas that those dreams might birth.”

Chaz’men Williams-Ali is making his LAO debut in the role of Nate. Recently, he was principal tenor at Theater und Orchester Heidelberg, where he appeared in roles including Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly and the Prince in Rusalka. In the States, the musician sang the part of Spinner in Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up In My Bones in its premiere production at Opera Theater of Saint Louis in 2019.

Williams-Ali, 34, believes that the music of Highway 1 is, in a word, “romantic. It’s like a 20th-century romantic piece. There are some jazz elements to it,” he added, “but not as many as people would think, like from the Harlem Renaissance. It’s a simple story about complicated people because no one is as two-dimensional as they seem on paper. But when you start to listen to the score, there are moments when the text of the piece and the music aren’t exactly saying the same thing.

“[Yet] the music is extremely approachable,” he continued, “whether you’re an opera lover or a newcomer to opera music. It almost puts you more in mind of Leonard Bernstein or somewhere between Bernstein and Puccini. I’m excited for everybody to hear it.”

Indeed, The New York Times, in a 2021 review, described the opera as “Still’s one-act stunner. … Though stylish, the music is unabashedly approachable. If played more widely, Still’s aesthetic might attract modern-opera skeptics who have rejected works from the modernist or minimalist camps that dominate the 20th-century repertoire currently performed in America.”

For research, Williams-Ali, who is in the process of relocating to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, with three young children and his wife, pianist Aurelia Andrews, said that he spent time “talking to my family members about that era. ‘What was popular?’ [I would ask], looking at pictures, how people dress. ‘What were the common thoughts of the day?’

“Nate talks about [Walt] Whitman and Shakespeare and Schopenhauer,” the tenor noted. “My being in Germany, not that far from Frankfurt, [where] Schopenhauer spent a lot of time, I can understand why people of color gravitated to ideas of atheism at the time. And during the Harlem Renaissance, [people] were pushing back on the idea of colonization and thinking that Christianity, as Black people knew it, was brought to them through colonization.

“That way of thinking wasn’t ubiquitous,” opined Williams-Ali, “but I can see how Schopenhauer’s works would appeal to them. It’s been interesting to pull these puzzle pieces together.”

As for the text alluding to the notion that Nate is a scoundrel, Williams-Ali believes the music to be “heroic. It’s beautiful and sweeping, [and] you can almost see how Still falls in love with these lofty ideas — [that] Nate sees bigger things for himself and in life. He feels trapped by the situation at the gas station.”

And while there is nary a gas station in sight in Zemlinsky’s The Dwarf — the opera tells the tale of the unrequited love between a nameless dwarf and the Spanish princess who toys with him — Conlon explained that Still’s and Zemlinsky’s works are nevertheless linked in several ways.

“The pairing of these two operas draws attention to the problem of what happens when art is suppressed,” explained the music director, who is augmenting the run of this double bill with the return of his Recovered Voices initiative. (The latest iteration takes place through a citywide series of lectures, seminars, and performances at various L.A. venues.)

Added Conlon: “There’s no similarity in the music of Still and Zemlinsky, but the important link in the history of music is why [suppression] happens. Still faced racism, and Zemlinsky faced genocide. He fled the Nazis, first from Berlin to Vienna and then from Vienna to New York; his music had been banned.”

Conlon went on to say that while the composers didn’t know each other, their incidental bond was that their lives were both negatively impacted — meaning the dissemination of their music was obstructed, to varying degrees, by racial prejudice. “In Zemlinsky’s case,” added the conductor, “it was literally with genocidal intent. In Still’s case, metaphorically so.”

Schaal agreed that presenting the two works in one evening is extremely meaningful. “To think about that kind of exile and buried music — I believe that the answer lives in this profoundly American night of music. What are we if not a nation of exile, cruelty, fleeing, and dreaming?” she said. “This evening of music is an America I’m proud of and is the answer to that question.”

Yet Still, who lived his last 30 years in Los Angeles with Arvey — their home in Oxford Square was designated a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 1976 — didn’t want his operas to be viewed only through a racial lens. “Different scholars have different opinions about why he said that, but that is a powerful clarity that he proposed,” exclaimed Schaal.

“I hear in his music that he’s reaching toward that reality, toward a possibility of understanding our humanity very, very, very differently. And without sacrificing the specificity of his own history and the history of opera and the history of the country, that is a very complicated proposal.”

Added Williams-Ali: “As a person of color, I think it’s wonderful that the story is not race-specific. Even though it’s telling a story of Black people at the time, being Black has nothing to do with the story. Look at other pieces where it’s crucial that the people are Black: the operas X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X, Fire Shut Up in My Bones, even Porgy and Bess.

“However you want to structure it,” the tenor stressed, “race is essential to those storylines. But for Highway 1, this could be anyone. They just happen to be Black.”