If there’s one orchestral instrument that is virtually a symbol of the orchestra’s tradition and antiquity, it is the violin — not only the most plentiful instrument in the ensemble, but one that (along with the viola and cello) has changed comparatively little since the 17th century, while brasses and winds have seen significant technological upgrades, and the percussion has undergone a vast expansion.

Composers and violinists, though, have long been intent on pulling the violin into modern times, and three new recordings look at quite different ways of doing that.

For Rachel Barton Pine, it’s a matter of using the violin as a blues instrument — an interest that dovetails with the Music of Black Composers her foundation has been funding since 2001. Jennifer Koh has long been interested in renovating the violin’s sound while also celebrating its traditional timbres, devoting equal time to recording both. Her latest, though, is devoted entirely to violin works by Kaija Saariaho, whose use of timbre is not limited by traditional notions of beautiful violin tone. And Hugh Marsh, a violinist who has worked a lot in various corners of the pop world, uses electronics to give his instrument a thoroughly fresh palette.

The violin may not strike you as particularly suited to the blues, but in that case, a refresher in the work of blues and jazz violinists like Sugar Cane Harris and Papa John Creach, not to mention Stéphane Grappelli, may be in order, and you might want to look into early recordings by Big Bill Broonzy and Lonnie Johnson, who played the violin before they were guitarists.

Rachel Barton Pine was onto the violin’s blues heritage when she was a young violinist, growing up in Chicago. As she wrote in the liner notes for Blues Dialogues: Music by Black Composers (Cedille), she grew up listening to her parents’ Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Charlie Musselwhite, and Paul Butterfield records, attending the Chicago Blues Festival, and sneaking into blues clubs when she was still underage.

But her bona fides as a blues fan are almost beside the point: you know from the opening bars of the opening piece — David N. Baker’s 1968 Blues (Deliver My Soul) — that she has the style in her heart, ears, and fingers. Baker, who based his work on his own choral setting of Psalm 22, opens this version with a fiery cadenza that has the violinist open with a quick blues run, complete with bent notes and a phrase-ending slide into the tonic, before settling briefly into a more meditative section, and then into conventional (that is, not particularly bluesy) pyrotechnics — all in the 50 seconds before pianist Matthew Hagle joins with the rich chords that suggest the work’s gospel-tinged origins as a psalm setting. For the rest of the piece, Baker moves between gospel and blues as well as a 19th-century salon sensibility that suggests an alternative universe picture of a violin and piano duo, offering this blues-gospel essay as a genteel after-dinner entertainment.

But her bona fides as a blues fan are almost beside the point: you know from the opening bars of the opening piece — David N. Baker’s 1968 Blues (Deliver My Soul) — that she has the style in her heart, ears, and fingers. Baker, who based his work on his own choral setting of Psalm 22, opens this version with a fiery cadenza that has the violinist open with a quick blues run, complete with bent notes and a phrase-ending slide into the tonic, before settling briefly into a more meditative section, and then into conventional (that is, not particularly bluesy) pyrotechnics — all in the 50 seconds before pianist Matthew Hagle joins with the rich chords that suggest the work’s gospel-tinged origins as a psalm setting. For the rest of the piece, Baker moves between gospel and blues as well as a 19th-century salon sensibility that suggests an alternative universe picture of a violin and piano duo, offering this blues-gospel essay as a genteel after-dinner entertainment.

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson worked on both sides of the musical street, composing classical scores and working as music director for Jerome Robbins and Alvin Ailey, but also writing string arrangements for Harry Belafonte and Marvin Gaye. His Blue(s) Forms for Solo Violin (1972) and Louisiana Blues Strut (A Cakewalk) (2001) are both for unaccompanied violin. Blue(s) Forms is a hybrid blues-classical sonata, with bravura outer movements etched in striking chromaticism and involved passage work, and a meditative central movement. Louisiana Blues Strut is built on a recurring call-and-response figure with a work-song quality, around which an extraordinary set of energetic variations is woven.

Pine offers several more overtly bluesy works, most notably, Clarence Cameron White’s Levee Dance (Op. 26, No. 2), a Heifetz encore favorite from 1927, with a fragment of the Spiritual, “Go Down Moses” nestled within it; Delores White’s alternately haunting and virtuosic four-movement Blues Dialogue (1988, revised 2016), and William Grant Still’s extraordinary Suite for Violin and Piano (1943), a richly-varied three-movement score that takes in bent notes, glissando, and other blues moves in a witty, technically bracing series of character sketches. Another Still movement, “The Blues” from his Lenox Avenue (1937) — a bright-edged rent party piece — is included as an encore on the album’s digital edition.

Pine moves farther afield, as well, though most of her selections keep close to the broader theme of black composers’ engagement with popular and folk currents, some — but not all — with exclusively black roots. Noel Da Costa, for example, based the five movements in his A Set of Dance Tunes for Solo Violin (1968) on William Bradbury Ryan’s Mammoth Collection, a book of English, Scottish, and Irish reels, jigs, hornpipes, clogs, and other dances — as well as what are called “Ethiopian melodies” — published in Boston in 1883. To today’s ears, several of the pieces Da Costa chose to revamp sound like country fiddling, and in transforming them into a neo-Baroque suite, he sacrificed nothing of their essential quality; nor does Pine, who plays as though she had a gig at a hoedown.

Wendell Logan’s 1988 arrangement of Duke Ellington’s In a Sentimental Mood is an expansively varied showpiece, but beneath the virtuosic surface, it offers a fascinating exploration of the song’s harmonic implications. Errollyn Wallen, a British composer born in Belize, is represented by Woogie Boogie (1999), a rollicking, syncopated, work that’s less driven by pop influences than its title suggests.

Charles S. Brown’s A Song Without Words (1974) picks up on the Mendelssohnian tradition, in the sense that its violin writing is shaped with all the qualities of a vocal line, but Brown’s version is more plaintive, wistful and contemporary. Daniel Bernard Roumain may have borrowed a few 19th-century display moves as well, in his Filter (1992, with a cadenza added for Pine in 2018), but he has updated them thoroughly, asking for a rich timbral palette (including a scratchy, high-pressure approach to bowing) and a considerable measure of dynamic fluidity.

Amid this relatively light-spirited celebration of black composers, Pine includes a recent work that touches on the other side of the black experience in contemporary America. Incident on Larpenteur Avenue, a 2018 work by Billy Childs, is a tone poem in sonata form, about the shooting of Philando Castile by a police officer during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, as his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds and her four-year old daughter looked on, with Reynolds streaming the incident live on Facebook.

Childs captures this tragic drama in tense, dramatic music, packed with pictorial touches — for example, violin pizzicatos, representing the gun shots, a chordal piano figure suggesting Castile’s dying breaths, with violin bursts suggesting Reynolds’s anger, and most wrenchingly, the sonata recapitulation suggesting that events like this continue to occur, a point highlighted by the work’s closing bars, which leave the music unresolved.

Pine and Hagle give the piece a stunning performance, showing all its terror and sadness, but also shining a spotlight on the many beautiful turns in a richly chromatic score. The collection is the second installment in Pine’s black-composers series, following Violin Concertos by Black Composers of the 18th and 19th Centuries, issued in 1997. Pine is a busy player with lots of interests in the standard and contemporary repertory. But here’s hoping another decade won’t elapse before we hear Volume 3. The repertory is at hand: through her RBP Foundation, she has collected some 900 works by 350 black composers from around the world, and while much of the foundation’s Music of Black Composers is about preparing and disseminating materials for students, getting these pieces on disc is obviously a must.

The violin was Kaija Saariaho’s first instrument, but her notion of what the violin can do has undoubtedly been expanded by her adventures as a composer for both acoustic and electronic instruments. Jennifer Koh has been particularly fascinated with her music in recent years. She has been playing Graal Théâtre — the violin concerto Saariaho composed for Gidon Kremer in 1994 — since at least 2006; I heard her give it a stunning performance in New York, in 2009. And she included the four-movement Frises (2011) on the second installment of her Bach and Beyond series, in which she pairs the Bach solo Sonatas and Partitas with contemporary scores.

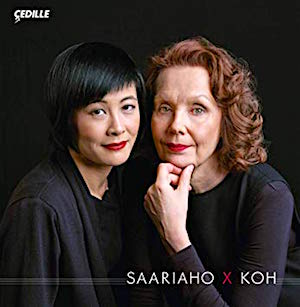

Koh’s latest album, Saariaho X Koh (Cedille) is devoted to Saariaho’s chamber music, with first recordings of Light and Matter (2014,) a piano trio, and the cello and violin duo version of Aure (2011), which also exists in a violin and viola edition.

Koh’s latest album, Saariaho X Koh (Cedille) is devoted to Saariaho’s chamber music, with first recordings of Light and Matter (2014,) a piano trio, and the cello and violin duo version of Aure (2011), which also exists in a violin and viola edition.

The centerpiece, though, is Graal Théâtre, which closes the disc. The solo violin line in this 30-minute concerto is energized and virtually continuous, and with constantly changing articulation, timbre and intensity. The ensemble balances also seem always to be in flux, with percussion, winds, strings and keyboard morphing into varying amalgams and winding around the solo violin line, sometimes chaotically, sometimes with a sense of dramatic urgency. It’s one of those works that seems to reveal more with every listening.

But that’s often the case with Saariaho’s music, as Koh demonstrates with a selection of variously scored chamber pieces. Tocar (2010), for violin and piano (Nicolas Hodges), opens the album with a whisper of bittersweet melody that, with the piano line fully supporting, becomes increasingly dense. The two instruments are in an interesting standoff here, moving independently and often busily, with the violin line working out dense variations on the wilting theme that opens the piece — but also occasionally tumbling into tightly intertwined passages.

In Cloud Trio (2009), in which Koh is joined by Hsin-Yun Huang, violist, and Wilhelmina Smith, cellist, the violin writing is often stratospheric and nimble, and uses extended techniques (whistling edge-of-the-bow timbres, for example) that yield an otherworldly sound. The viola and cello lines are equally varied, and all three are constantly in motion, creating the kind of dreamscape that makes Saariaho’s music so mysterious and appealing.

Light and Matter (2014), for piano trio (with Hodge and cellist Anssi Karttunen), a souvenir of time Saariaho spent in New York, living in an apartment with a view of Morningside Heights, near Columbia University. Struck by the changes of light from sunrise to sunset, and from Fall to Spring, she wrote this piece as a hybrid tone poem and (aural) action painting, capturing the changes in the park as it moved through the daily and seasonal cycle.

Interestingly, Saariaho accomplishes this with the kind of vividness that Haydn brought to the opening of The Creation, yet extended techniques and contemporary stylistic freedom actually give her a broader and less predictable palette, despite the fact that Haydn had a full orchestra at hand. She begins with a rumbling haze, gathered around a low C, and she ends the piece with a quiet shimmer, also on a C.

In between, the individual instrumental lines grow clearer, eventually coalescing into events rather than themes — the wind in the trees, the violence of a storm, an eerie stillness, gradual shifts of texture and hue. Timbres soar independently at times; elsewhere they are tightly interlocked. At the end of its nearly 14-minute duration, you have a clear sense of having been somewhere and observed a world of changes. Then you remember that this variegated vision that Saariaho created is really just a view from a single vantage point, overlooking a park over time.

Aure (2011), for which Koh is again joined by Karttunen, is a 95th-birthday tribute to Henri Dutilleux, based on the six-note motif that opens the third movement of Dutilleux’s Mémoire des ombres (1997). Dutilleux’s work, for three children’s voices and orchestra, is a meditation on a line from The Diary of Anne Frank, “Why us, why the star?” In the Dutilleux, the motif is sung by a child’s voice, and is expanded upon assertively, by the full orchestra.

Saariaho’s treatment is quieter and more reflective, its melancholy theme given first to the violin, with variations appearing in the cello. The violin and cello lines wind tightly around each other, as if they are searching jointly, and uneasily, for some sort of meaning or resolution. Dramatic pauses seem less like real section breaks than moments to ponder before undertaking the search afresh, and the violin’s artificial harmonics hang over the piece like an eerie glow.

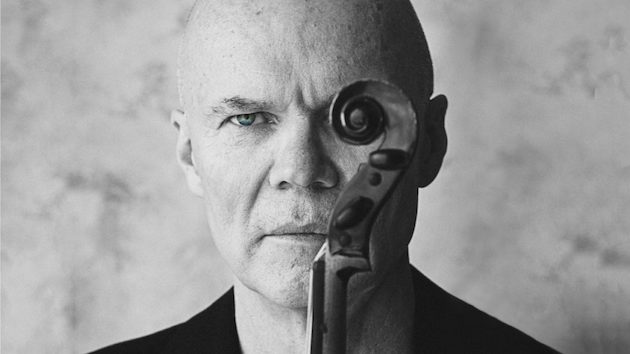

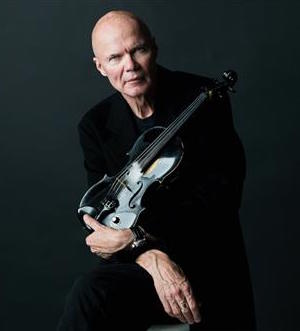

Hugh Marsh’s Violinvocations (Western Vinyl) was an accidental creation, a project the Toronto-based violinist undertook after he traveled to Los Angeles for a recording project that was cancelled shortly after he arrived. Marsh decided to remain in Los Angeles for 183 days and to start a project of his own, setting himself the goal of recording at least one new work every day.

Violinvocations includes eight of those pieces, and is a fascinating listen, particularly if you’re interested in what can be done with a pair of electric violins — one at standard pitch, the other a baritone violin, tuned an octave lower — and a collection of sound-altering pedals.

According to the notes, no other instruments or music creation software was used, and several of the pieces were recorded in single takes. Given the density of sound Marsh gets in these pieces, that’s hard to believe, particularly in the absence of a list of Marsh’s pedals. On the other hand, if you have an idea of what’s available in instrument pedals — looping devices, digital delays, various kinds and qualities of distortion and sound shaping — you can piece together some (though not quite all) of his moves. And let’s face it: There has always been a lot to be said for the degree to which players can mystify audiences with the variety of sounds they can produce.

According to the notes, no other instruments or music creation software was used, and several of the pieces were recorded in single takes. Given the density of sound Marsh gets in these pieces, that’s hard to believe, particularly in the absence of a list of Marsh’s pedals. On the other hand, if you have an idea of what’s available in instrument pedals — looping devices, digital delays, various kinds and qualities of distortion and sound shaping — you can piece together some (though not quite all) of his moves. And let’s face it: There has always been a lot to be said for the degree to which players can mystify audiences with the variety of sounds they can produce.

Marsh opens his set with I Laid Down in the Snow, a piece that begins (and ends) with the kind of crackling you hear if you dig out an old 78-rpm shellac disc. Whether Marsh intended it, the paradoxical effect of this antique sound introducing his collection of high-tech tone poems is akin to that of the opening slate of the first Star Wars film (“A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away ...”).

What emerges from there is a hazy, distant, sustained tone, overlaid with wave-like washes of sound. When a theme emerges, its timbre is closer to that of a trumpet than a violin, with wavering intonation that conjures images of an amplified fly, buzzing a mournful theme amid a spacey wash that could be described as new-agey, if it weren’t so menacing.

A modified version of the trumpet/fly timbre, with a bit more violin sound in it, returns in Miku Murmuration. Named for Hatsune Miku, an anime character that was introduced as the mascot for a piece of Japanese voice synthesizer software, but took on a life of her own as a video singer, the track begins with a cartoonish burst of vocalism (created, according to the notes, with a guitar effects pedal) and melts quickly into a modal chant against a light chordal drone. As it turns out, the modal “vocal” line, though it recurs, is one of several styles Marsh has his violin imitate. There are comic turns, and purely virtuosic figures, as well as lines with leaps beyond what a living singer (who wanted to remain in serviceable vocal health) could do, all swathed in rich reverberation.

The repeating pizzicato figure that runs through the first half of Thirtysix Hundred Grandview is processed to create a rounded, percussive sound. Eventually, it morphs into a looped rhythmic figure, against which Marsh adopts a brassy timbre for a slow-moving chord progression, with occasional hints of the violin (in brief glissandos), and somehow also produces a light clicking sound, like a sci-fi ratchet of some sort.

Percussive sounds, including thumpy, resonant pizzicatos, a lighter version of the ratchet, and the crackling from the opening track, animate The Rain Gambler, an exotic soundscape that also includes backwards sounds and brief flecks of heavily processed violin melody. Like most of these pieces, there is no real narrative arc here; Marsh seems more interested in creating and exploring otherworldly textures and lingering, slowly changing atmospheres — like Saariaho in Light and Matter, in a way.

While certain timbres turn up on several tracks, each is really a distinctly imagined sound world. The most varied and involving piece is A Beautiful Mistake, in which Marsh’s instrument takes on the qualities of a heavily distorted guitar, a rock soloist without a band to trade ideas with. But there are also many attractions in Da Solo Non Solitario, in which the violin dons a constantly changing collection of masks, and Across the Aether, in which the crackle returns, this time like weirdly ghostly footsteps, against a pianissimo, metallic backdrop. From this menacing backdrop, a reverb-laden pizzicato figure arises, becoming a lively, attractive theme.

Marsh closes the set with She Will, the most conventional of these pieces, establishes an unchanging (except in its slowly reconfigured timbre and texture) sustained chordal backdrop, from which a woodwind-like looped figure, scratchy electronic figures in stuttering rhythms, and a graceful Hindustani-tinged melody in a clear, flute timbre, battle for primacy, the flute theme eventually winning.

Western Vinyl’s publicity materials don’t say how many pieces Marsh created during his 183-day project, or what will become of them. But if they are as varied and as inventive as these eight, more of these adventures would be welcome.