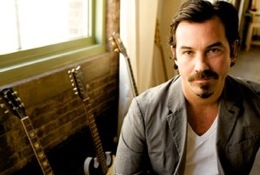

If you grew up in the 1990s you probably know Duncan Sheik, the singer-songwriter who arrives this week to perform songs from his musical Whisper House with the San Francisco Symphony. His 1996 debut hit, Barely Breathing, about a stalled relationship, marries its catchy groove to an emotional honesty. Sheik's intimate performing style and unamplified guitar, freshens the conventional pop sentiments.

The Symphony's program crosses boundaries with the same thoughtfulness that Sheik shows in his career (which now includes the Tony Award-winning musical Spring Awakening). It's a high-rent version of the Magik*Magik Orchestra's experiment with the Dodos several weeks back, an attempt to find music in the classical canon that would match Sheik's and entertain and intrigue the audience for Whisper House. And I'm betting that the Symphony's board is hoping that imagined audience is younger than the orchestra's season subscribers.

Surely some of the new visitors to Davies Symphony Hall this week will return, but when they do, they probably won’t be hankering after Mahler, Berg, or Messiaen. There’s a tendency among us hard-core classical fans to think of “light classics” as a kind of lure — that, once the newbies have dipped their toes in the water, they’ll learn to love Debussy and Bartók and others.

The reality is likely a bit more complicated. Sure, people are up for new adventures, yet they also come to the Symphony as intelligent adults with already defined musical tastes. We have to respect that. The object of “crossover” programs is not to capture a few pop music listeners, spirit them away to the classical fort, and hunker down against the onslaught of mass culture. Once the walls come down, they have to stay down.

This is the lesson of the startling success of the KDFC radio station. As Bill Lueth, the station's managing director, told me, KDFC is not in the business of teaching a radio audience what to like, but of responding intelligently to their tastes. If a piece from a film soundtrack goes down well during a midweek morning show, Lueth will program more of it. If the audience loves Lang Lang, they get to hear his recordings. A portion of that audience also tunes in to the more “serious” Tuesday night San Francisco Symphony broadcasts, because they want to, not because it's good for them.

Many longtime classical fans are dismayed by KDFC, crossover albums, and the like because those manifestations of classical music don't fit their tastes. They like music that is more edgy, modernist, or intellectually demanding. Some are suspicious of mass-marketing success – Lang Lang, Renée Fleming, and others in that mold are seen as superficial crowd-pleasers. Such attitudes about the aesthetic purpose and premise of the classical tradition go back to the beginnings of Romanticism and are entirely honorable.

Music by Any Other Name May Sound as Sweet

Yet if the subject is bringing new audiences to classical music and sustaining the large classical music institutions that will, eventually, depend on those new audiences, then our Romantic zeal may be misplaced. “Sometimes classical music defeats itself by its own name,” wrote SFCV’s Matthew Cmiel, of the Magik*Magik Orchestra/ Dodos concert. What I take away from Cmiel's sentence is the idea that there's a huge amount of classical music out there, much of it extremely entertaining and not difficult at all to “get.” But fetishizing classical music's intellectual pedigree and cordoning it off from the rest of the music world, makes it seem difficult, undesirable, and even irrelevant. In reality, most classical musicians are remarkable for the breadth of their interests. As soon as a musical style or repertory is commonly available to composers, you find them integrating it into classical pieces. And a lot of pop artists do the same thing. Sheik didn’t continue writing in the vein of Barely Breathing; he did some albums influenced by his lay Buddhist practice, composed several songs that were more complicated, and finally wrote a musical based on an early-20th-century Viennese play.

Ultimately, the greater the variety of music the San Francisco Symphony plays, the greater its connection to the city and region around it. This is why the Duncan Sheik concert, as well as the screening of Charlie Chaplin’s classic The Gold Rush with the Symphony playing the film’s score, seems so hopeful to me. These events don’t scream “classical,” though they are, nonetheless. Sustaining interest in classical music is not a matter of initiating listeners into the heart of the mysteries of Wagner or of explaining pieces in a program note. It’s about creating more rooms in the musical mansion that already includes a fair proportion of the world’s greatest music.