Creative geniuses fascinate us. We devour New Yorker profiles of the world’s most extraordinary people. We flock to biopics of great artists and scientists. We may hire a creativity coach to help unleash our own latent potential. Still, it is challenging to understand the workings of a truly innovative mind. Genius is hard to capture, and geniuses can be real jerks.

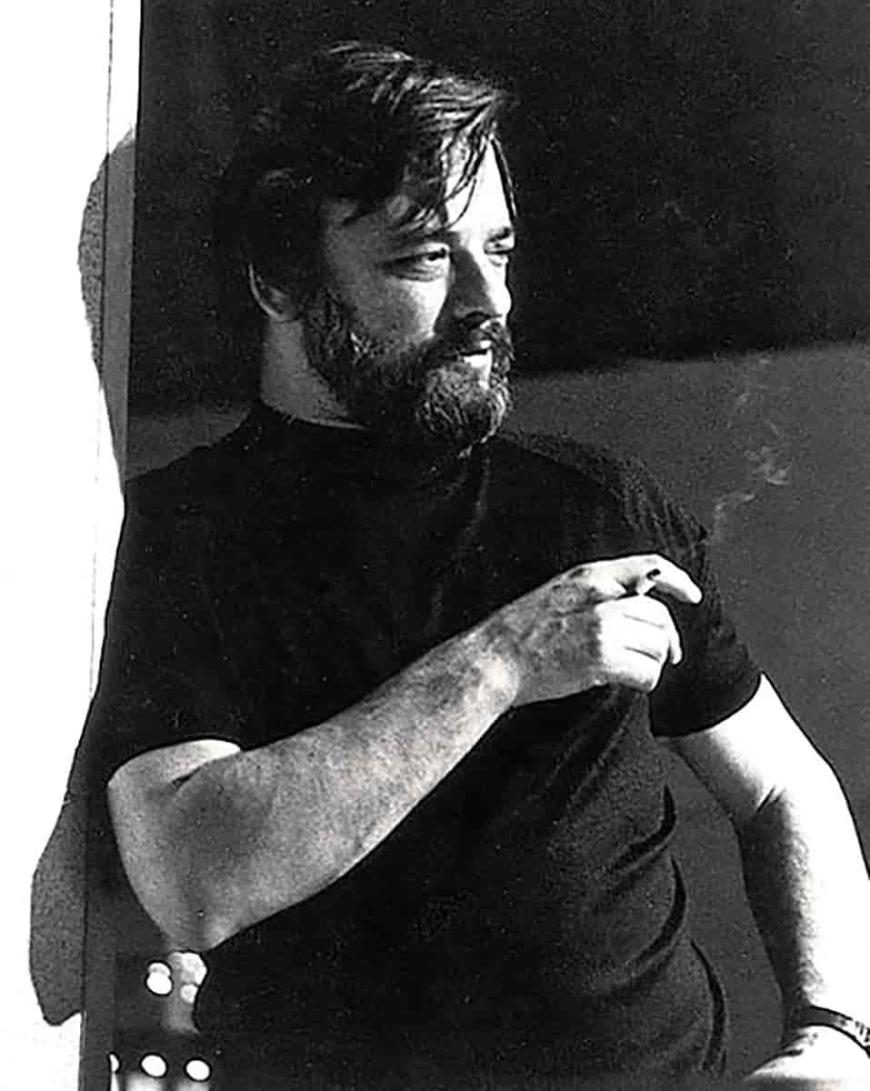

That’s the task composer Mason Bates and librettist Mark Campbell set themselves in The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, which recently concluded its run at San Francisco Opera. Fortunately, in portraying the obsessive, frustrating brilliance of their title character, the pair could look to another great musical work about an obsessive genius. Bates and Campbell’s opera has parallels with Sunday in the Park With George, the Pulitzer Prize-winning musical with a score by Stephen Sondheim and book by James Lapine that opened on Broadway in 1984.

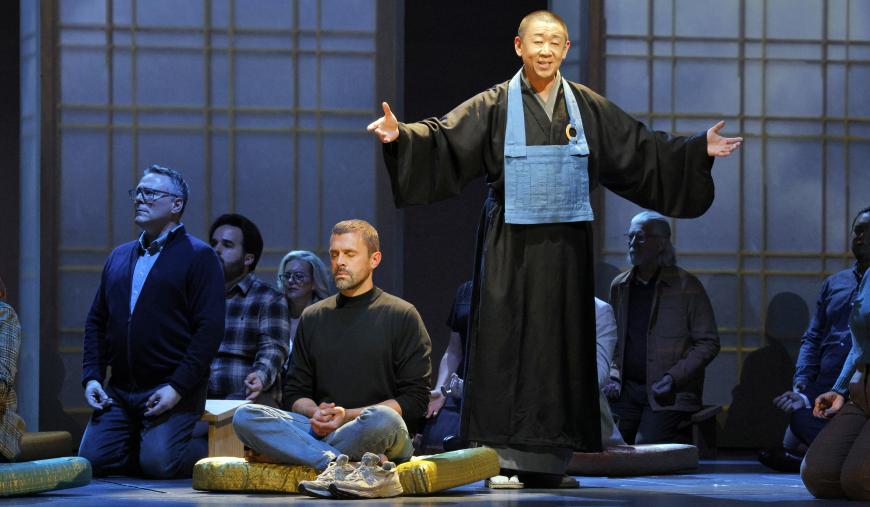

When I attended The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs at SF Opera the other week, I noticed similarities between the two works almost immediately. After a prologue in which 10-year-old Steve receives a workbench from his father, we meet the adult Steve Jobs in 2007, at the Apple event where he introduces the iPhone. Over propulsive ostinatos and synthesizer sounds, Jobs sings fast-paced, patter-like lyrics extolling this new device, while a chorus of tech journalists provides counterpoint.

It’s reminiscent of “Putting It Together,” a synth-driven patter song in Act 2 of Sunday in the Park. There, a 1980s multimedia artist named George sings about the challenges of making art, set against a chorus of cocktail party guests. Both numbers even feature lots of conceptual nouns with “-tion” rhymes. Jobs: “Inspiration, comprehension, not to mention communication.” George: “Mapping out the right configuration, starting with a suitable foundation.”

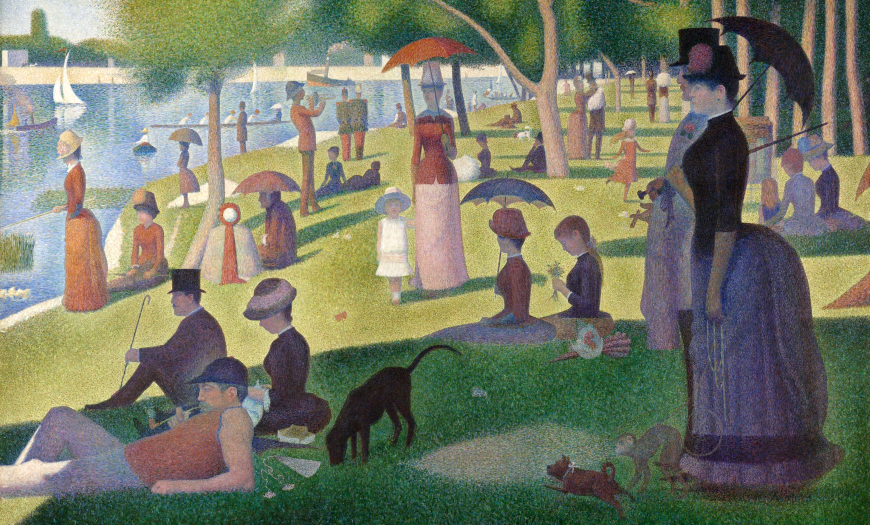

Amazingly, the events of Jobs’s life have some parallels with the highly fictionalized version of the life of Parisian painter Georges Seurat that Sondheim and Lapine present in Act 1 of Sunday in the Park. As 20-somethings, both characters have girlfriends who they often ignore in favor of intense creative work. Then, the women get pregnant, and the men don’t know how to deal with it. Seurat and Jobs refuse to step up and take responsibility as fathers, and Dot and Chrisann are left to handle motherhood on their own.

Yet at the same time as the man pushes his loved ones away in the real world, he incorporates them into what he’s creating in an oblique gesture of tenderness. Seurat makes Dot the most prominent figure in his massive painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Jobs names one of Apple’s first computers the “Lisa,” after the baby daughter who he publicly disowned.

There’s an extra layer of connection between art and life in that Sunday in the Park is itself the creation of an obsessive genius. As soon as the musical premiered, many people considered it Sondheim’s most personal work. Eventually, he embraced that characterization, titling his two books of collected lyrics Finishing the Hat and Look, I Made a Hat, after lines from the song he wrote for Seurat about the pleasures and agonies of artistic creation. In the preface to the first volume, Sondheim lays out his principles of lyric writing: “Content Dictates Form. Less is More. God Is in the Details. All in the service of Clarity.”

Sondheim’s personal artistic principles share a kinship with the principles that Seurat recites as his artistic credo throughout Sunday in the Park: “Order. Design. Composition. Tension. Balance. Light. And harmony.” And, of course, they are also reminiscent of Jobs’s design-first, detail-obsessed ethos, with his call to always “simplify.”

There are no such catchy artistic credos from Bates or Campbell, but both know and admire Sondheim’s work. For a 2015 project that invited prominent composers to arrange Sondheim songs for solo piano, Bates created a version of “Putting It Together.” The mid-2010s was also around the time when Bates and Campbell were working hard on Steve Jobs, which premiered in Santa Fe in summer 2017.

For his part, Campbell told an interviewer, “Almost everything I know about writing for opera, I learned from studying Sondheim’s work. Any success I have had is due to him.” I wouldn’t be surprised if Campbell introduced some deliberate Easter eggs into his libretto for Steve Jobs. At one point, for example, the chorus sings that Jobs has “no life in his life,” which is also a lyric in Sunday in the Park.

But the Sondheim influence on Steve Jobs goes deeper than just a fun quotation or two. There are structural parallels, especially in how the two works conclude.

In the incredibly moving finale of Sunday in the Park, the contemporary American artist George makes a pilgrimage to Paris, encounters the spirit of his great-grandmother, and receives words of comfort and artistic inspiration from her. “Move on,” Dot sings to George. “Understand the light. Concentrate on now.”

Meanwhile, the finale of Steve Jobs takes place at the tech mogul’s funeral. His widow Laurene exhorts the attendees — and, by extension, the audience — to put away their phones and “look up. Take in the light. Be here now.” It follows the Sunday pattern: A beatific woman with a warm mezzo voice, who loves the difficult hero despite his flaws, provides a forward-looking two-word mantra. “Move on.” “Look up.”

Then, as Dot disappears back to wherever muses live, George finds inspiration in some lines from her journal about Seurat: “White. A blank page or canvas. His favorite. So many possibilities.” And as Jobs prepares to cross over to wherever the dead go, he finds consolation in remembering his first creative endeavors at the workbench in his parents’ garage, thinking, “Now is a fine place to start.” In the original production of Sunday in Park, the blank canvas that dropped down on the set shone brilliant white and then faded to black. At SF Opera, the iPhone-like plastic boxes of the Steve Jobs set glowed brilliant white before fading to black. George has found the balance, light, and harmony he sought; Steve has finally found simplicity and Zen Buddhist peace. The shows leave us with a bittersweet but hopeful feeling: People die, but great work endures, and you can always make more of it.

Not everything about Steve Jobs works the same way as Sunday in the Park. For instance, Sunday creates more distinctive small roles for the ensemble. The soldiers, shopgirls, boatman, old lady, and little girl that populate the park all have far more “color and life” than the anonymous secretaries, designers, and tech journalists in Steve Jobs.

On the other hand, Steve Jobs engages much more directly with its protagonist’s mortality. Contemporary American audiences may not know that Seurat died suddenly at the age of 31 — when the characters announce this near the start of Act 2, it always draws some muted gasps. However, many of us in the San Francisco Steve Jobs audience can remember the day Jobs died in 2011: the mourning that seemed to descend over the city’s business districts, the bitten apples that people left in tribute outside the Apple Store.

As such, if Sunday in the Park is subtly shadowed by death, then Steve Jobs is immersed in it. Jobs displays physical weakness (Seurat never does), he argues about his death with his wife and his spiritual mentor, and he even returns as a ghost at his own funeral. Sunday is about a lot of ordinary humans in a park — including the artist who painted them, who wasn’t very successful in his own time — learning that art can grant them immortality despite their physical passing. Steve Jobs is about a man who reached vast heights of success and fame in his lifetime and arrogantly assumed that he could cheat death but had to learn that he was only human after all.

It’s easy to see why Steve Jobs took so much inspiration from Sunday in the Park. It’s a great example of how to write a musical about an innovative genius for an audience that is skeptical of great-man narratives. Neither work shies away from depicting its protagonist’s impatience and self-absorption. Also, neither is a straightforward cradle-to-grave biography. Following Sondheim’s mantra that “content dictates form,” Sunday in the Park is an impressionistic musical about a post-impressionist painter, while Steve Jobs is a cyclical opera about a man who subscribed to the cyclical philosophy of Buddhism.

There’s even an odd parallel between Seurat’s pointillist paintings, which juxtapose little dots of pure color to make up an image, and the pixels that are used to display color on an iMac or iPhone. The frequent staccato synthesizer sounds used by both Sondheim and Bates feel like an aural representation of these dots and pixels. Furthermore, as Bates wrote on his website, “We agreed that this story needed a nonlinear, ‘pixelated’ structure. … Any one of [the] short scenes seen on its own, like a single pixel, is but a flicker of light. But arranged together, these pixels animate an image, a life.” Perhaps Seurat, Sondheim, and Jobs would all agree.