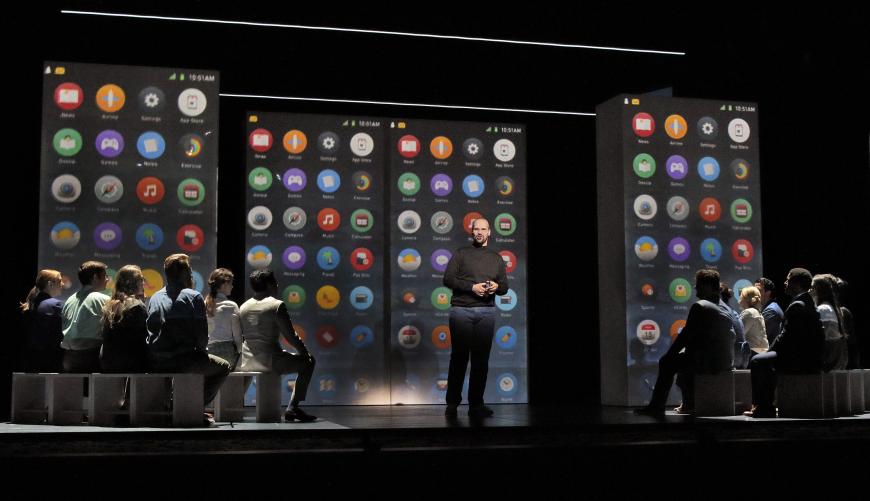

Composer Mason Bates will be in the orchestra pit when his 2017 opera The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs opens at San Francisco Opera, Sept. 22 at the War Memorial Opera House. It’s a bit of luxury because with him manning the electronics, there’s a bit more interactivity between the copious electronic elements in the score and the rest of the orchestra.

“It’s like live cooking,” he says. “Whereas when it goes out without me, it’s more like triggers on a synthesizer — a little less flexibility. You have to make it work for a nonspecialist if you want to have orchestras and opera houses do this sort of thing.”

In fact, the subject of the opera couldn’t be more aligned with the interests of the composer, who, as DJ Masonic, has for years worked clubs, doing all kinds of electronica. For one of his high-profile residencies, in 2015 at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., he created the KC Jukebox series, which mixed immersive stagecraft and a wide variety of musical styles and artists. With Mercury Soul, which he co-created in San Francisco, live classical groups and DJs mixing dance beats come together in a club atmosphere for a “post-classical rave.” During his five-year residency with the Chicago Symphony, he and composer Anna Clyne created MusicNOW, partnering with a local DJ collective to curate pre- and postconcert music that often dipped into adventurous programming but concentrated on creating an attractive social milieu for younger audiences.

Like Steve Jobs, Bates has made it into the tech world, working with Google and YouTube on the YouTube Symphony Orchestra and with Cisco at its Partner Summit. One of his latest projects is Philharmonia Fantastique, a 25-minute concerto and animated film by Gary Rydstrom, with animation direction by Jim Capobianco and music by Bates, subtitled “the making of an orchestra.” It’s an introduction to the orchestra but, beyond that, an investigation of the orchestra’s connections to technology and human creativity. BBC Music Magazine said of the work, “It’s a noble enterprise, with deeper ideals about human diversity and unity. Bates is, as ever, an engaging musical storyteller.”

Bates is one of the most-performed living composers of orchestral music, and part of that comes from his emphasis on storytelling and theatricality. He calls himself a “theatrical animal,” though he only has a single opera among his large catalog of works. But the industrious composer is aiming to fix that as well. The Metropolitan Opera has co-commissioned a new work from him, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, with a libretto by Gene Scheer, which premieres at Los Angeles Opera in fall 2024 before reaching the Met the next season.

The 46-year-old Juilliard-trained Bates has the gift of looking younger than he is. His conversational manner is somewhere between the welcoming breadth of his Virginia upbringing and the more intense communication style of Juilliard and UC Berkeley, where he got his Ph.D. in 2008, studying with Edmund Campion at the Center for New Music and Audio Technologies. We talked as Bates drove in for an early orchestra rehearsal for Steve Jobs.

What do you think the opera is about essentially?

At its heart it’s about a man who learns to become human again. And it could really be about Steve [Everyman] — that’s what [librettist] Mark [Campbell] and I always said. It’s about a man who has lost his way, and through the intervention of his wife and, to some degree, his Buddhist mentor, he learns to appreciate true human connection. What’s interesting about Steve as the subject of an opera is that he’s really both a protagonist and an antagonist. You fall in love with him, and then you fall out of love with him in the way that he treats people. He’s so dismissive and tries to be controlling. So it’s really a journey, almost a deathbed vision, to see his life again.

You can hear it in the music. The music begins, literally, in the space of a computer. It’s like samples of early Macintosh gear, clicks and hard drives and such.

Is that the key to the gestalt of this piece?

I wanted to find everybody’s sound world. This is an opera about this guy who changed the way we communicate, so [I thought] communication [style] could be an element of the opera. And so, Steve has this quicksilver, busy, almost nervous energy that at its best can be creative and fun, like when he’s in his garage dreaming things up, and at its worst can be domineering. And when I was opening the opera, I thought it would be a kind of nice piece of metafiction to have samples of early Apple gear dreamily floating out of the electronics. As a way of saying, without saying, “The person you’re about to explore has touched all of us, even if you’ve never met him.”

You worked with a very experienced librettist, Mark Campbell, who has been writing opera texts since 2004 and musical theater before that. Was that an advantage for you, and what was your collaboration like?

Mark is a master librettist. I went to him because I felt his particular gifts would really suit this piece. Early on, before he was a librettist, he was like an adman, coming up with advertising copy — he’s really good at hooks. And since this opera was going to be more of a “number opera” with arias, I felt like he would be great at that.

I will say the process is best described as productive friction. He had so many operas under his belt, and this was my first. But I had also studied a lot of libretti, having studied with Arnold Weinstein at Columbia [who wrote libretti for composer William Bolcom], and had some clear ideas of how I wanted the libretto to be. And luckily, we found a way to meet in the middle. I mean, Mark would say to me, “I understand that you want to have a bunch of rhymes, but there are different ways to do that that are less distracting for the listener.” So he would do internal rhymes.

But in terms of the actual structure and shape of the opera, we were always right with each other. We wanted this kaleidoscopic, fast-moving sequence of scenes that would create these juxtapositions in Jobs’s life in a way that you can’t really do in a representational medium.

The last thing to say is that when we got to the opera house in Santa Fe [where Steve Jobs premiered in 2017], he was just an incredible ally. We would work so closely together. We would share our thoughts internally and then offer something to the director or conductor, and I really loved that.

So you had thought a lot about writing opera before this?

Well, I had actually written a couple of unproduced — and rightfully so — operas. Brad Woolbright, the artistic administrator at Santa Fe Opera, sent me, in 2017, the week of the premiere, an email from, like, 2003. I had gone to Santa Fe, I had gotten to know Brad, and I was trying to pitch him on an opera I’d written just out of Juilliard. And I was like, “Hey Brad, I’d love you to consider this for Santa Fe. I think it would be great on your stage.” And he was like, “Yeah, we love what you’re doing, but we need to wait a little bit, give you a little more time to grow.”

My point is all the work I did up to Steve Jobs was incredibly useful. In startup [terms] those “failed companies” helped me be ready for this one.

Opera is much more collaborative than most of the work one does as a composer.

Yeah, and I guess the key is “best idea wins.” And your music has to be able to stand up to different interpretations, and you, as an artist, need to be a person of the theater. You need to be ready to jump in there and adjust notes if it’s not working for the singer, to maybe write a more concise interlude if it’s long.

I was trained pretty doggedly by John Corigliano at Juilliard to really work on your structure before starting to build the cathedral. And that means thinking through the big problems as much as you can early on so you don’t have drastic structural issues to deal with. And I would say that I think about storytelling in every piece I do.

You worked beside Anna Clyne at the Chicago Symphony, and she’s just one of a number of contemporary composers who use electronics. Do you track what other people are doing in classical with electronica and pop influences?

Of course, totally. Anna is really one of the best because she uses the electronic elements as a kind of complement; it’s not the whole point. It’s not like some IRCAM thing, where it’s all about the technology. For me, [electronics] have always been almost like an extension of the percussion section that can add this new element. But at the end of the day, it’s really about what the instruments are doing and how the electronics are adding something to that.

For me what was really fascinating was discovering that adding an element of sound design — almost along the lines of Pink Floyd or something — feels like you can do some of the storytelling that [Hector] Berlioz and [Franz] Liszt and [Richard] Wagner were exploring when they were trying to find new orchestral sounds to help them tell these programmatic stories. And I just decided to run with it.

I’m thinking about the end of the first act of Tannhäuser, where Wagner deploys two sets of horns to make you feel that some are close and some are far away. You could do that with sound design today.

That’s exactly it. I have this piece called Liquid Interface, which is kind of like a water symphony in the vein of [Claude Debussy’s] La mer. For that piece, I start with recordings of glaciers calving in Antarctica; I have actual sounds of a hurricane. You can take the storytelling to another level. You just have to be really careful that the musical material that you’re mainlining everything to is very strong and is leading the show. Because if you just add in sound design over whole notes, it won’t feel like it really fits in the space.

Let’s break down electronica for a moment. You’re into techno, but there’s a lot of varieties of that. So where would you say you land in that scene?

“Electronica” is an umbrella term for this whole genre, that, like “classical music,” just became the term for everything — to a lot of people, “techno” is just the term. Well, that’s the first term, but there’s all this other stuff. So I use “electronica,” which is any kind of electronic beat that maybe had its origins in dance music but has just evolved, in some cases, away from the dance floor. I love techno, and when I was in Chicago, I fell in love with that industrial sound. And you’ll hear that a little bit in Steve Jobs — there’s an interlude that has some heavy industrial beats. … But for the launch theme, it’s really more of this quicksilver-fast patter, probably up there in the drum and bass tempo, if not the actual beat pattern.

But I also have a real love for downtempo and trip-hop and ambient music. In pieces like Liquid Interface, I feel like the music of glaciers also had this element of slow trip-hop because there’s so much more space between the beats that you’re allowed to explore. In the opera you also hear elements of ambient electronica, in the music of Kōbun, the spiritual advisor to Steve. He just exists in this world of dreamy sound design — prayer bowls, wind chimes, and processed synthesizer. And that was definitely influenced by the ambient music of, like, Aphex Twin. There’s a whole world of electronica out there, and just inhabiting one part of it would be like being a jazz musician and only doing bebop.

And at the end of the day, you have to make it your own. So even in [Bates’s 2009 piece] Mothership, those [four-on-the floor] beats come and go, like for 20 seconds. There are all these trapdoors in the piece. If you just had four on the floor for nine minutes, I promise, in the concert hall, it would just fall flat. So whatever you’re influenced by, you do need to pass it through your musical language.

Correction: As originally published, this article misstated the name of the librettist of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. It is Gene Scheer, not Leonard Foglia. We regret the error.