Wally Heider was already something of a legend among sound engineers when he opened his eponymous recording studio in the Tenderloin in 1969. Though based in Los Angeles for much of the 1960s, he’d been making regular forays north for years, perfecting his remote recording techniques while capturing epochal events like Charles Lloyd’s career-making 1966 performance at the Monterey Jazz Festival and the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967.

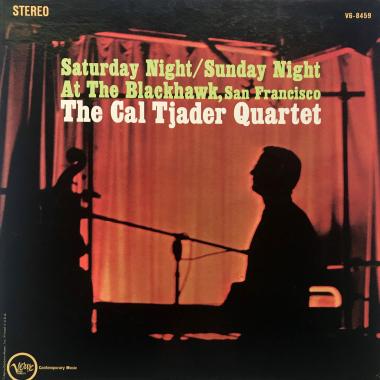

Realizing that the burgeoning San Francisco scene was in dire need of a well-equipped recording facility, he opened Wally Heider Studios at 245 Hyde St., across the way from where he’d recorded the Cal Tjader Quartet album Saturday Night/Sunday Night at The Blackhawk, San Francisco for Fantasy in 1962. (Contrary to many online citations, Heider isn’t credited on Miles Davis’s classic Blackhawk albums from 1961, though he did record Herbie Hancock’s second date with the trumpeter, which was eventually released as Live at the 1963 Monterey Jazz Festival).

By the time the doors opened at Wally Heider Studios in March of 1969, he was deeply enmeshed in the Bay Area music scene, and in that first year, the studio made an indelible mark with Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Green River, Jefferson Airplane’s Volunteers, and Quicksilver Messenger Service’s Shady Grove. A succession of era-defining projects followed, including beloved albums by Van Morrison, the Grateful Dead, and various combinations of Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Purchased in 1980 by songwriter and producer Michael Ward and two partners, the rechristened Hyde Street Studios has been solely owned and run by Ward since 1985. After nearly four decades, the studio is thriving in the face of tectonic shifts that have shuttered just about every similar Bay Area facility. Hip-hoppers and funksters, punk rockers and jazz improvisers have all made their mark in the expansive Studio A or one of the smaller rooms, including the Dead Kennedys, Green Day, Digital Underground, Cake, Tupac Shakur, Santana, and Meshell Ndegeocello.

A new documentary project, When the Sound Hits the Walls, aims to tell some of stories that have unfolded at Heider/Hyde Street, while also capturing the way the nondescript building continues to serve as a buzzing hive for a menagerie of musicians, producers, and technicians. Envisioned as a 10-part series that’s part historical chronicle and part present-tense verite, the ambitious undertaking introduces the hybrid concept with a fundraising concert by the latest iteration of the Headhunters at Menlo Park’s Guild Theatre on Aug. 26.

An album-by-album series dedicated to classic projects recorded at the facility could easily run for four or five seasons. The Hits the Walls team is more interested in looking at the various technologies and scenes that shaped the music manifested in the studio. Rather than focusing exclusively on the glorious past, “we also want to capture what’s happening there now,” said producer Chris McGrew, who’s also the drummer for the opening act at the Guild Theatre show, Seal Party, a band that came together at Hyde Street.

Serving as the liaison between the studio and the documentary team, McGrew connected producer John Montoya with director Albert Lopez. He has also helped shape the project’s inside-team vision, “because there’s no way to tell the story from the outside,” McGrew said.

“It’s not a museum piece. For 50 years, the studio has been a hub for really creative, not corporate, music. Artists had access to the board from the beginning. Ward has operated the space like a coop, running Studio A and leasing out the other rooms. It’s a sacred space and meeting place for musicians across the spectrum.”

Planned episodes of the documentary series focus on the technical team assembled by Heider during the wild and wooly 1970s, an insider’s look at musicians and producers navigating the oft-competing demands of art and commerce, and the studio’s role as a proving ground for cutting-edge electronic instruments.

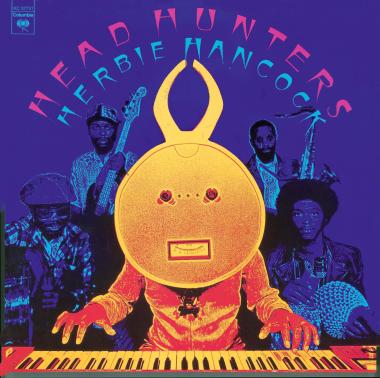

Saturday’s Headhunters concert exemplifies the series’ 360-degree perspective, celebrating the studio’s legacy while investing in the creation of new music. Few artists did more to put Wally Heider Studios on the map than Herbie Hancock, who used the facility as his base of operations during years of intense creative ferment, first with his revered post-bop sextet Mwandishi in the early 1970s and then with Head Hunters, the hit 1973 funk/jazz album that turned the keyboardist into a commercial force.

Drummer Mike Clark was recording sessions for Charlie Brown cartoon specials with pianist/composer Vince Guaraldi at Wally Heider’s when his best friend, bass guitarist Paul Jackson, was downstairs recording with Hancock’s new band, which featured Mwandishi reed player Bennie Maupin, drummer Harvey Mason, and percussionist Bill Summers. Clark took over the drum chair for the next album, 1974’s Thrust, which was also recorded at the studio, and his drum work on the tune “Actual Proof” quickly entered the funk vernacular (the track has been sampled more than a thousand times).

Though he idolized innovative jazz drummers like Elvin Jones, Philly Joe Jones, and Tony Williams, Clark embraced his role in the Headhunters, “though I had to really fight David Rubinson to play it the way I did,” he said, referring to Hancock’s longtime producer. “I was the new guy, the white boy, the whole goddamned thing, and he stopped the tape and said, ‘No one’s going to know where ‘one’ is.’”

Having been turned on to Nichiren Buddhism by Hancock, Clark sequestered himself upstairs in Studio B “and chanted 20 minutes to be immortalized like Elvin,” the drummer recalled. “When I came back, instead of arguing, I told David, ‘You’ve got a great idea,’ which wasn’t true. It was terrible. He said you’ve got one take to make it in. We did it, and when we listened back, Herbie high-fived me. ‘You just made history, Clark.’”

After decades of intermittent tours and recordings, the Headhunters are more active now than they’ve been in many years. Co-led by Clark, a Sacramento native who came of age on the Bay Area jazz scene in the 1960s, and percussionist Bill Summers, the quintet features a brilliant cast of New Orleans musicians, including Kyle Roussel on keyboards, Chris Severin on seven-string bass, and alto saxophonist Donald Harrison. Last November, the group released the studio album Speakers in the House and launched an extensive tour marking the 50th anniversary of the band’s original album. And just two weeks ago, the Headhunters followed up with the Ropeadope album Live From Brooklyn Bowl.

In the days before Saturday’s concert, the group will be settling into Hyde Street to record another album, a process the filmmakers will document for the first Hits the Walls segment. In a highly unusual move, the series is underwriting the recording session and giving the music to the musicians. The Guild Theatre, which is a nonprofit venue, is supporting the series, and Bay Hotel is putting the band up while they’re in town. The filmmakers are still lining up other sponsors and underwriters for the project.

“My plan is to replicate what we’re doing with other legacy artists,” said producer Montoya, a former San Francisco resident who co-produced Vicky Funari and Julia Query’s documentary about the campaign to unionize erotic dancers in North Beach, Live Nude Girls Unite! (2000). “We’re inviting [the artists] back to the studio to make some new music, funded by our budget, and giving them their masters, which we’ll license back to use in the film.”

By most accounts, Hyde Street is the Bay Area’s longest-running modern studio, though the single-room studio Different Fur also opened in 1969. With its den of recording spaces, Hyde Street offers a critical mass of creative energy that often spills out of one room and takes on a life of its own. Countless tunes have been written and collaborations sparked by artists toiling away in the wee hours. Ten episodes will only scratch the surface of the music that’s materialized from this hub Wally Heider started. A close-up investigation of an institution that helped shape the music we grew up with, the series promises to be an intimate appraisal of world-shaking sounds.

“I’m not sure anyone walking the planet hasn’t been touched by the music that came out of that studio,” Montoya said.