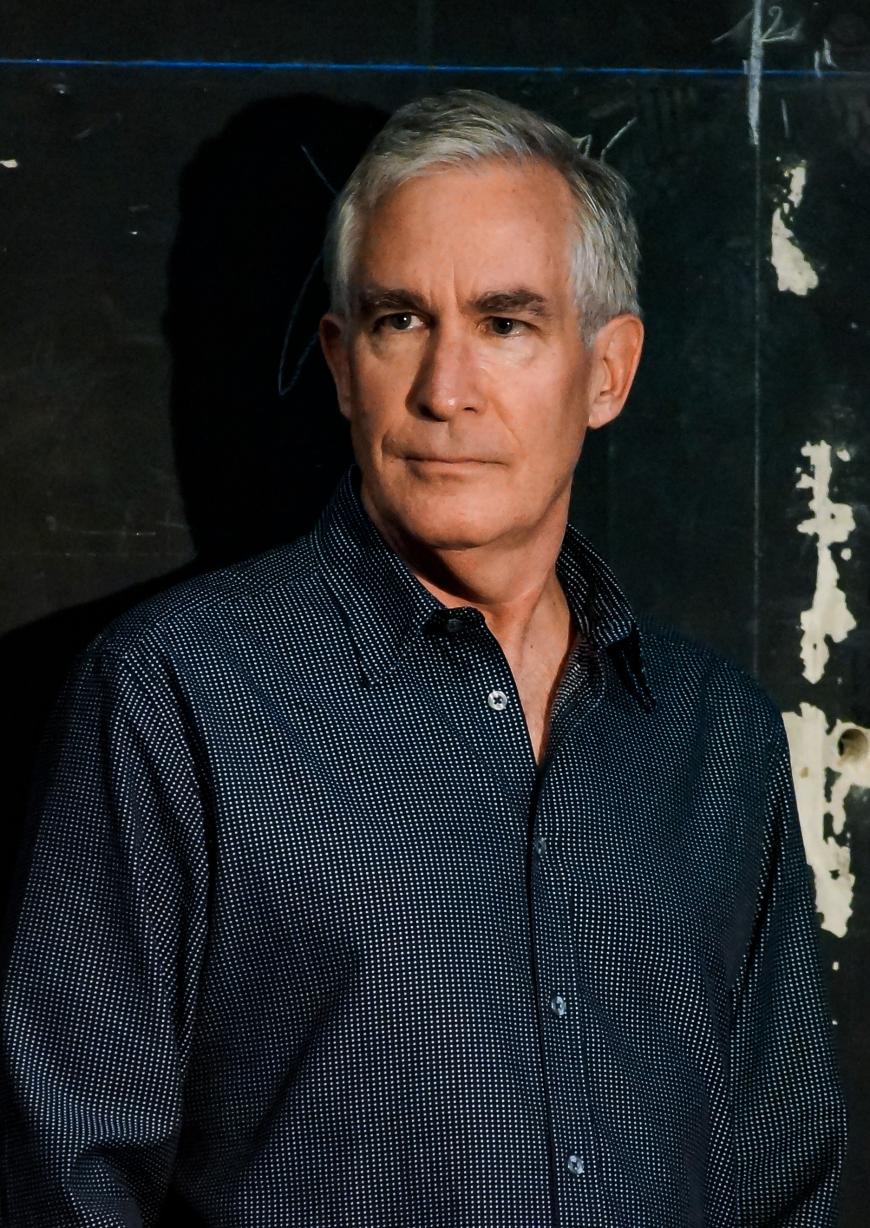

When veteran opera stage director Peter McClintock finishes a long day of rehearsals, he usually heads home, wherever that is at the moment. Could be St. Petersburg, Toronto, Shanghai, or his Manhattan apartment. Sometimes he unwinds by watching television and reading. Or he studies a new language to add to his linguistic creds in German, French, Russian, Italian, and Chinese. What he doesn’t do is listen to music.

“I like quiet ... and to turn off my brain, when I can,” said McClintock with a wide grin, in a Zoom interview on a recent Friday evening in late August. He had just finished that week’s rehearsals of restaging Robert Carsen’s Eugene Onegin for San Francisco Opera. (Performances run Sept. 25 – Oct. 14.) McClintock worked with Carsen on the original 1997 Metropolitan Opera production and has reset the work eight times on stages around the world in the past quarter century.

The world of opera benefits when McClintock recharges. Because when he does switch on his brain professionally, his neural hard drive contains the information for restaging hundreds of operas. He’s worked with many of the world’s marquee opera directors on their original productions, including Andrei Konchalovsky, Patrice Chéreau, Franco Zeffirelli, and Francesca Zambello.

McClintock’s methods to restage operas include consulting the heavily notated original production score and the original production’s dress rehearsal video for technical issues, such as lighting and props. Much of the work, however, comes down to his memory. Artificial intelligence would be unable to do McClintock’s job unless Silicon Valley figures out a way to download his grey matter.

“At the Met, I was always amazed by how many shows Peter staged every season,” said Jeffery McMillan, San Francisco Opera’s public relations director, who joined SFO from the Met in 2016. “The practical opera knowledge concentrated in that man is truly impressive and rare.”

Carsen’s Onegin is new to San Francisco Opera, but its 2022 revival marks the fourth time in as many years that McClintock has restaged it. The last time SF Opera presented Onegin was in 2004, in a Netherlands Opera (now Dutch National Opera) production directed by Johannes Schaaf.

Carsen’s concept of Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s adaptation of Alexander Pushkin’s novel in verse about unrequited love remains as fresh today as it did at its Met premiere, according to McClintock. “Twenty-five years later it doesn’t feel dated at all,” said the Ukiah-born and raised McClintock, who began his career at SF Opera in 1985 as a production assistant. “Everywhere we’ve done this production, it’s done well.”

With its bare-bones set (sometimes a gilt chair angled just so on a raked stage), ornate period costumes, and light projections from three sides, the production “ends up being like a light box,” said McClintock, referring to the audience’s point of view of the proscenium. “Inside the light box,” he continued, “Carsen wanted to create a very specific world through the costumes and strip away the houses and gardens to focus on the interrelationships.”

Directing an opera is already a large undertaking with big money at stake, lots of personalities to manage, and high expectations. Restaging a production adds additional challenges for a director, who must hew to the original concept but also coach something different from the work.

As McClintock resets productions of Onegin on the world’s top opera stages, as well as other operas by noted directors, his job as a revival director, he said, is to recreate the work as it was conceived. In Onegin, “I’m trying to represent Robert’s ideas the best way I can and not be slavish to very small technical details,” said McClintock, who first worked with Carsen on the 1989 San Francisco Opera production of Mefistofele.

Carsen’s creative vision of Onegin doesn’t change from production to production, apart from adapting to each physical theater, said McClintock, whose early operatic influences included growing up with two opera recordings his parents owned: Madama Butterfly with Renata Tebaldi and La traviata. A high school visit to San Francisco for an opera performance also sowed an early interest. By the time he earned a theater degree from UCLA in 1982, he knew he wanted to direct opera.

“The older I get the more I ponder, and try to get better at, what my role is as a revival director,” said McClintock, who has also directed projects of his own, including a cinematic version of Pagliacci for Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2021. “I’d never done an opera on film before,” he said, adding, “I liked it; it worked out well.”

Today Carsen’s Onegin is viewed by critics as an iconic realization. Its 1997 Met world premiere, however, wasn’t that well received, said McClintock, who joined the Met in 1988 while still also working on San Francisco Opera productions for a time. “That first season audiences saw it as too stripped down; it didn’t get good reviews. It was considered too avant-garde.”

The current revival (sets and costumes) of Onegin was purchased as a package from the Canadian Opera Company, where McClintock directed the restaging in 2018 (Canadian bass-baritone Gordon Bintner reprises the title role in the SF Opera production). The Toronto-based opera company, in turn, had purchased the 1997 Carsen production from the Met.

Onegin’s original set and costume designer, Michael Levine, and choreographer Serge Bennathan have joined McClintock in San Francisco for shorter periods of time to work on the opera. McClintock said he appreciated having different sets of eyes from the 1997 production to fine-tune its elements, from a touch-up of gold paint where a chip had marred a gilded chair to a breathy nuance of movement for the dancers in Onegin’s swirling waltz scene, with its tsunami of sound sonically mirroring the emotional push-and-pull of Onegin’s heart.

Pushkin is ever present on McClintock’s mind as he restages Onegin around the world. “I’m a total Pushkin fan; I’m a Russophile,” he said. It was working with conductor Valery Gergiev in 1991 on War and Peace at San Francisco Opera that prompted him to first study Russian, in which he’s now fluent.

Carsen carried around a copy of Pushkin’s verse novel while directing Onegin, McClintock said. While assisting Patrice Chéreau on his new production of Leoš Janáček’s From the House of the Dead in Vienna in 2007, McClintock noted the late opera and film director carried around a copy of Dostoevsky’s Notes From the House of the Dead.

“Working with Patrice, as well as Robert — that kind of director is unbelievable,” said McClintock. “His [Chéreau’s] faithfulness to the text, his textual analysis, was the basis of everything he did. I follow that example,” said McClintock, who carries around his own copy of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin.

Onegin will be the last opera McClintock resets before he takes nearly a year off until September 2023, when he’ll head to Berlin to restage Elektra. In the meantime McClintock plans to continue teaching in the Met’s young artist program, do some traveling, and reacquaint himself with the piano “after 40 years of not playing.”

But for now his focus is on Onegin. By the time the curtain rises on opening night — McClintock always attends the opening of revivals he’s staged, he said — he’ll be looking to be “caught up in a living, breathing drama that real people will believe.”

“Opera is the hardest to get right and for all the people to be at their highest level,” he said. “When opera is at its purest, with all guns blazing, there’s nothing like that.”

Correction: The article, as original published, stated an incorrect year for when McClintock graduated from UCLA.