“We make our offering to the dead at either the cemetery or home,” explains conductor Alondra de la Parra, who makes her much-anticipated San Francisco Symphony debut with a Nov. 1 family concert celebrating Latino culture.

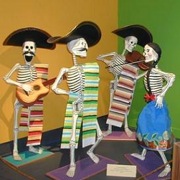

“The ‘Day of the Dead’ is a fun party,” she continues. “Families spend hours making food — huge casseroles — that they leave for the dead people. We give them wine, flowers, skulls made from sugar and chocolate, and bread made to look like bones. We also make second helpings of everything for the living. We read poetry in honor of the dead that is filled with dark humor, and tell humorous stories about how they died so we can laugh and release the pain. We also write poems for the living that are parodies and satires about how the person would die.”

As de la Parra constructs an imaginary poem about her own death on the podium, the reasons the Symphony tapped her for the assignment become clear. The Mexican-born, Manhattan School of Music–trained conductor, who turns 29 the day before her SFS debut, founded the Philharmonic Orchestra of the Americas (POA), which is based in New York, in 2004. Composed of young professionals dedicated to promoting the work of youthful soloists and composers of the American continent, it’s only one achievement of the first woman from Mexico to conduct in New York City. Not only is she a champion of living composers of the Americas, but she also knows a host of young soloists, including pianists Kristhyan Benitez and Ana Karina Alamo, who join author Laura Esquivel (Like Water For Chocolate) to perform in the concert.

De la Parra envisions the program as being one extended dance. It begins with Revueltas’ Noche de jaranas, an excerpt from what she calls his “fantastic, humongous” piece for film, La noche de los Mayas. The performance includes dancers who will illustrate a competition among males to see who will break a piñata. Then comes Ginastera’s Danza del trigo from the ballet Estancia, a slower dance of the wheat to a “very beautiful, simple tune with beautiful harmonies and orchestration.” Soon comes Moncayo’s joyful Huapango, a work many consider the unofficial national anthem of Mexico.

Just a few weeks after the Berkeley Symphony Orchestra opened its season with music by its new creative adviser, Berkeley-based Gabriela Lena Frank, de la Parra will conduct selections from Frank’s Three Latin American Dances. The fun dance mixes musics of the Spanish and native Latin American culture. Then, after Esquivel reads her Spanish narration for Saint-Saëns’ The Carnival of the Animals, the concert ends with Márquez’ Danzón No. 2, currently the most popular piece of music in Mexico, with roots in Cuba’s sensual dancón.

“The dead will be very happy with this program,” says de la Parra. “They’re going to be dancing.” So will folks with the perspicacity to get tickets.