The long shadow of the pandemic cast a palpable mood over the Sound Room on Thursday, when Oakland tuba player and composer Jonathan Seiberlich assembled a stellar cast of players to mark the release of his new album, Isolation Suite.

It wasn’t just that this music is a visceral response to the disorienting first year of COVID. Seiberlich, who has quietly become an essential and singular figure on the Bay Area music scene over the past decade, turned the night into an extended sojourn through the recent era’s precarious emotional terrain. Initially, I wasn’t sure this was what I needed or wanted from an evening of music, but at the end of an often riveting 80-minute performance, I was grateful for his openhearted aesthetic.

In many ways the concert evoked the different musical realms in which Seiberlich thrives. On any given night, he might be found performing with the San Francisco Symphony, the Nomad Session wind octet, Honor Brass Band, the Circus Bella All-Star Band, Kyle Athayde Dance Party, or various Jazz Mafia aggregations, particularly Grateful Brass. At the Sound Room, he was joined by Jazz Mafia conspirators Adam Theis on trombone, Mike Olmos on trumpet, Tommy Occhiuto on alto and tenor saxophone, and Darian Gray on drums.

A masterly tuba player, Seiberlich has gleaned and recombined elements from jazz, New Orleans brass bands, funk horn sections, and chamber wind ensembles to serve his particular purposes. With all the horn players seated, the musicians played with the subtle dynamics and compressed energy of a chamber group, while Gray expertly defined an array of grooves, often generating delicious tension with double-time passages. Rather than focusing on brass band polyphony, Seiberlich writes overlapping lines for the horns that blend and subside to leave space for solos.

Before that conversation started, however, Seiberlich opened the evening with an extended brass meditation that began with long solo tuba notes. While he explained that this breathing practice helped him stave off anxiety during lockdown, it probably wasn’t the best strategy to warn that the exercise “might feel like it lasts an eternity.” But with his recitation of Denise Levertov’s poem “Talking to Grief,” this slowly accreted minimalist brass soundscape took on a different feel and significance.

Loss and angst were definitely emotional threads running through the evening, but so were joy and celebration, particularly with a gorgeously calibrated version of Charles Mingus’s “Jump Monk.” Led by Occhiuto’s slashing alto solo, the arrangement reveled in Mingus’s surging melody without trying to evoke the unbridled energy of the classic 1956 live album Mingus at the Bohemia.

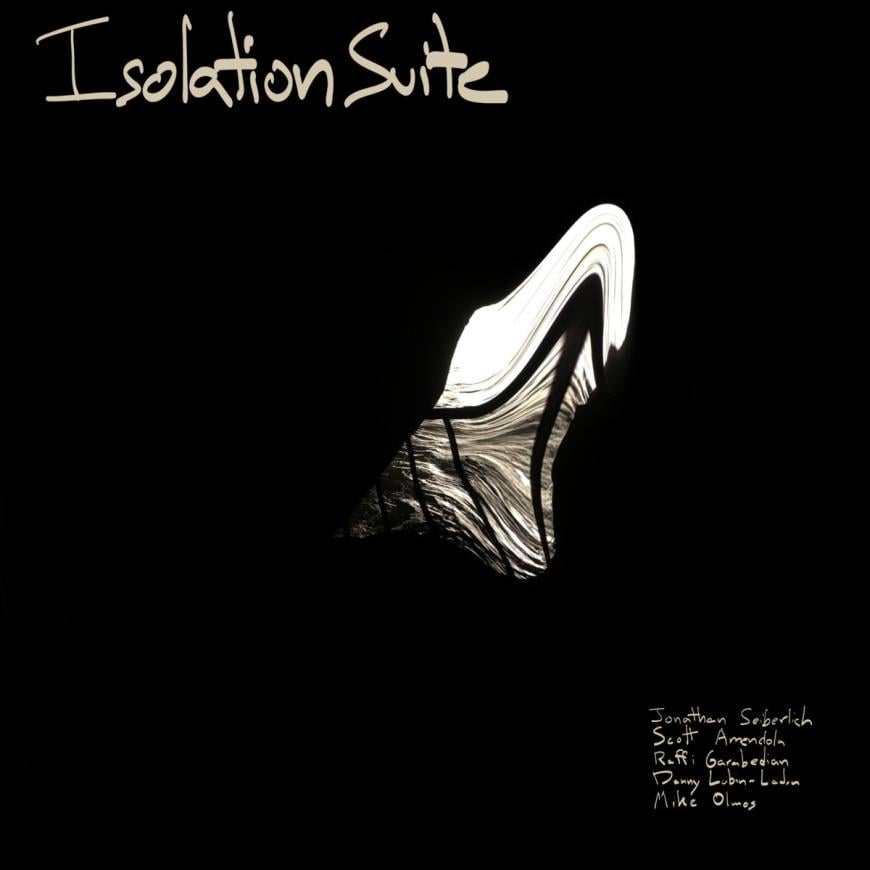

The second half of the concert featured Seiberlich’s five-part Isolation Suite, which he’s just released on the San Francisco-based label Slow & Steady Records. The piece was written for outdoor Jazz Mafia gatherings and driveway sessions at body percussionist Keith Terry’s house, and each movement captures a specific set of sensations and feelings, from the vertiginous alarm of “Alive for Now” to the dismay and sadness of “Crying Over the Kitchen Sink,” a ballad that featured Seiberlich on piano. The concluding, herky-jerky “Fallout” evoked the pandemic’s whipsaw reverberations, though by ending with brass long tones, like how the concert began, Seiberlich suggested that there’s a path forward, whatever grief we might carry with us.