I’ve been impressed by at least one aspect of every opera I’ve seen mounted at Z Space. It’s gratifying to see what a team can accomplish given limited resources, and low-budget operas are some of the best I’ve seen.

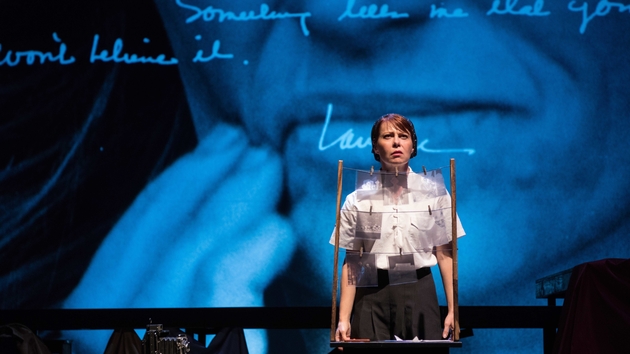

On Saturday, Left Coast Chamber Ensemble premiered Christopher Stark’s From the Field, a micro-opera it also commissioned. The best features here are portability and the talent of its cast: It’s easy to imagine that this production for voice (Nikki Einfeld), string duet (violinist Anna Presler and cellist Leighton Fong), and effective projection design (Andrew Lucia) will receive additional performances.

But the presence of multimedia also dilutes impact. The flawless Einfeld plays Dorothea Lange, who created iconic photographs of the Depression. But she’s made to share the spotlight with writings of a 19th-century explorer and interviews with a climate-change expert; the effect is that of a documentary with an unusually involved (and yet not exceptional) underscore.

Laura Schwendinger’s Artemisia, on the other hand, is sumptuous on every level. It also was a higher-budget affair, and not written specifically for Left Coast, although Saturday saw the premiere of the arrangement for chamber ensemble, conducted by Matilda Hofman.

The Artemisia in question is Gentileschi, the Baroque painter who achieved renown for her realistic images of women from mythology — and for taking her rapist to trial.

That villain appears here, but he is not the story. Betany Coffland brings nuance to every side of Artemisia — the wronged, the hard-working, the headstrong, In one of librettist Ginger Strand’s zingers, Artemisia declines her assistant’s suggestion to address her patron as “master.”

One major accomplishment is that the story includes rape without indulging in what I’ve come to think of as The Rape Scene, a titillating pageant of a woman suffering. Part of the difference here is that the action isn’t unfolding in real time to the hapless heroine: Rather, a mature Artemisia is telling the story, which morphs between that of biblical Susanna, compellingly sung by Marnie Breckenridge, and her own.

This Artemisia repeatedly stops the action to comment on the bodies in their formations, calling attention to tropes within the genre of classical painting. Motioning to the way the skin twists, she sings, “It may sound proud, but I got that right.” (Apparently, art historians — men — have wondered how Gentileschi could have painted the female body so accurately. Perhaps she looked down?)

As Artemisia, Coffland literally shapes the scene, physically moving the delightfully evil Jonathan Smucker, one of Susanna’s assailants (along with Igor Vieira) to sit on the chaise, where he becomes Tassi, her own rapist. In the ensuing scene, Artemisia relives her trial — but she’s now playing the interrogator.

Best of all is the secondary character, Artemisia’s male assistant Tommaso (beautifully sung by Kyle Stegall). As he writes her dictation, he echoes her speech; the effect isn’t sing-songy, but a pretty melding of timbres (and perhaps a nod to the high male voices in fashion at the time).

With so much to unpack, listening to the music can become secondary — but once you turn toward it, Schwendinger’s score is striking. Often, it’s the little things, like the intoning of “Susanna”: the stressed syllable rising before the terminal fall, a nagging presence grudgingly accepted. Or the resolutions of the diminished fourths in Tommaso’s aria, a breathtaking piece of worry and longing.

Most memorably, the music underscores Artemisia’s deteriorating vision. Tender, high-pitched glimmers shift so as to be out of reach. The shadows are flat-sounding chords: impressionistic, but with a distinctly contemporary sensibility.

The opera’s classicism, actually, is campy. Greek choruses commentate between scenes, wine-colored fabrics drape artfully (set designer Angrette McCloskey), and Susanna’s dress (costume designer Maggie Whitaker) nods to Flaming June. On the other hand, the opera’s “now” (Artemisia is 51) manages to look both contemporary and general. Tommaso’s stained but expensive-looking natural fibers would be worn in the gentrified Mission, and yet there’s no dissonance in watching him write with a quill (future status item?). In this effortless way, Artemisia moves through time, its actions as if captured by tableaux, but still timely.