Todd Field’s film Tár starring Cate Blanchett is a dark psychological portrait of a woman artist — the world-renowned conductor Lydia Tár — who as the film begins is at the pinnacle of her career. Tragically, by the end all that she has achieved will be lost due to iron-plated arrogance and an inability to control herself (verbally or sexually) in the era of #MeToo and trial by social media.

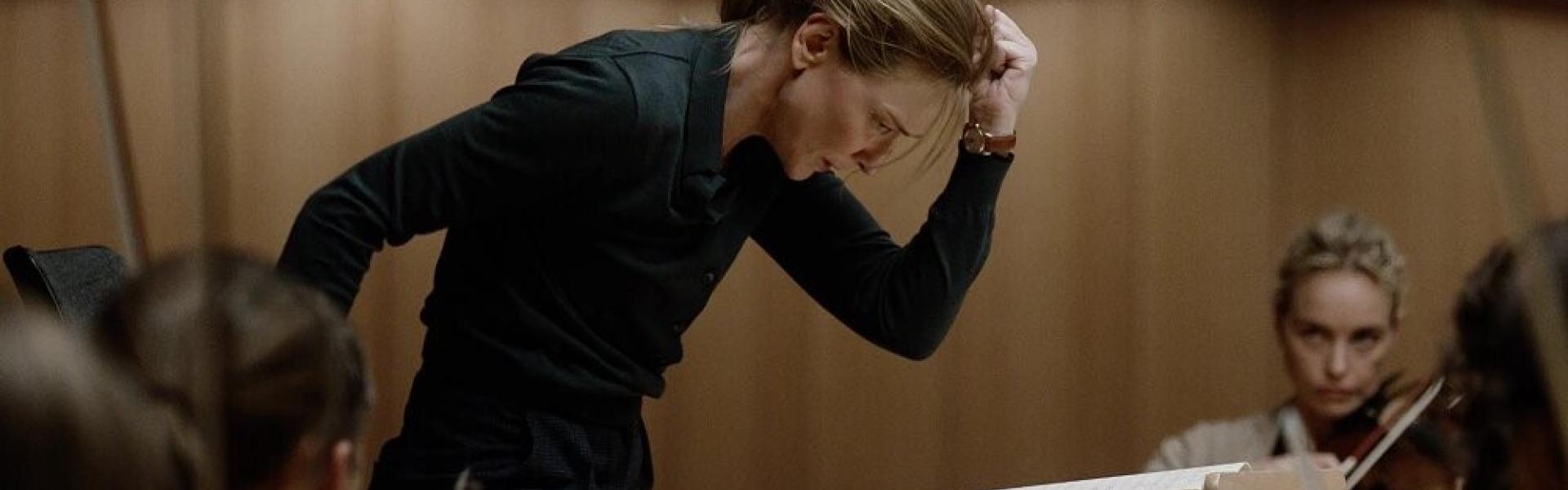

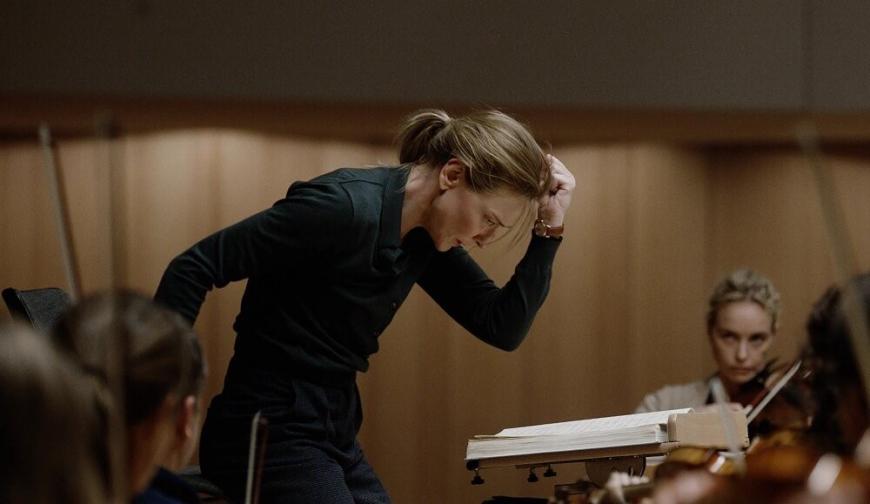

Simultaneously, the film has delighted classical music lovers and professional musicians alike for the way in which it draws back the curtain on the inner life and in-jokes of symphonic music-making — from the everyday realm of rehearsals, unions, and recording contracts to PR junkets and internecine orchestra politics to the subtle nuances of symphonic interpretation. It is an arena in which Lydia Tár has a lot to say.

There are two lengthy scenes early on in the film that prove particularly significant. The first is an onstage Q&A conducted by New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik. Initially, it’s a time-saving way to provide the audience with the necessary details of Lydia Tár’s stellar career: her mentorship with Leonard Bernstein, her trek into the jungle to study indigenous music, her Ph.D. from Harvard, and her Oscar, Tony, and Grammy awards. It is following this introduction that two questions are posed that resonate throughout the film.

“What is the role of the conductor?” the host inquires. “Some people say it is simply to be a metronome.”

With a combination of well-rehearsed personal charm and knowledge based on years of experience, Tár explains how on the one hand (literally) she is a human metronome. Her ability to maintain precise time is essential. It is with her other hand, she gracefully demonstrates, that she transforms time into an elastically modulating entity that provides interpretive inspiration for a performance.

It is a skill that she takes great pride in as she prepares for an upcoming recording of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, which provides a through line for the film. Her goal, she explains, is an elusive level of musical perfection that cannot be expressed in words. Her apartment floor is littered with albums. How did Claudio Abbado do it? Or Herbert von Karajan or Bernstein or Michael Tilson Thomas, whose rendition pops up on her phone alarm. That reference, though fleeting and dismissive on her part, is knowing, since Tilson Thomas’s high-contrast, tempo-fluid interpretations are sometimes criticized as indulgent.

The subject of the Fifth Symphony is also discussed in terms of its pivotal timing in Mahler’s life and his marriage to Alma Schindler. While the interviewer sees the union’s eventual breakup from Mahler’s perspective, Tár proposes that the reason the marriage failed was because Mahler insisted there could only be one composer in the family and Alma should subordinate herself and give up her compositional aspirations.

For the ultra-independent Lydia Tár, who off-handedly describes herself as a “U-Haul lesbian,” the domestic world, the one the audience never sees, is a gathering storm of conflict involving her wife (who is also the orchestra’s concertmaster, played by Nina Hoss), their young adopted daughter, and the coming mayhem that results from Tár’s past and current sexual liaisons and their bait of orchestra advancement.

Any number of playwrights and filmmakers have explored the perils and devastating impact of illicit sexual encounters (proved or unproved) that are linked to academic or professional advancement. And without question this theme is powerfully explored in Tár, and her self-inflicted fall is Shakespearean in scale.

The second significant encounter (that has later ramifications) takes place during a masterclass taught by Tár at Juilliard as she subjects the performance of a (nonbinary) conducting student to intense criticism. It begins with him conducting a stark modern work by the Icelandic composer Anna Thorvaldsdottir.

The student is asked what he takes emotionally from the piece. He has no substantial answer. She asks his opinion of composers like Mahler and Bach. His response, as his nerves become more and more frayed, is that he has no interest in old, white heterosexual composers, particularly Bach, whom he condemns for having so many children.

When Tár accuses him of being closed-minded and tries to demonstrate why Bach is as vital today as he was in his own day, the lesson falls on deaf ears. It is a moment of honesty, brutal though it may be, that will come back to haunt her. Personally, I can recall similar moments of students brought to tears in acting classes under the dictatorial leadership of Lee Strasberg.

Even as her world crumbles, Lydia Tár believes her genius and status will shield her from accusations of sexual misconduct. Her self-inflicted fall from grace is difficult to watch right up to the moment of the climactic performance of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony and its tragic outcome.