Los Angeles Opera is presenting an eye-dazzling production of Philip Glass’s portrait opera, Satyagraha,. On Nov. 1, the Los Angeles Philharmonic performed the world premiere of Steve Reich’s Music for Ensemble and Orchestra. Then on Saturday Long Beach Opera offered the first of two performances of Three Tales with its music by Steve Reich and visuals by video artist, Beryl Korot, Reich’s wife and regular artistic collaborator. In addition, the venerable Monday Evening Concerts will be performing Reich’s seminal Music for 18 Musicians on Dec. 17 at the Colburn School’s Zipper Hall.

The back-to-back performances of the new Music for Ensemble and Orchestra and Three Tales, which premiered at the Vienna Festival in 2002, offered an interesting intersection of Reich’s different trains of composition.

Music for Ensemble and Orchestra is a work that stems directly in its compositional template from the minimalist work that Reich pioneered in the 1970s. And while the music for Three Tales is grafted from the same roots, the style of the work (visually, musically, and intellectually) represents the multimedia creations that Reich has conceived in partnership with Korot.

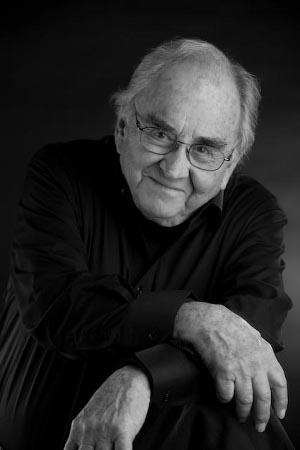

Now 82, Reich looked as spry as ever when he took to the podium for a preconcert chat at the Walt Disney Concert Hall moderated by Asadour Santourian, artistic administrator of the Aspen Festival.

“Did you compose Music for Ensemble and Orchestra with the musicians of the Los Angeles Philharmonic in mind,” he asked? To which Reich, with barely a moment’s reflection replied, “No. It was composed so any orchestra could play it. I want my music to be played. That’s how it lives”

As the first orchestral composition that Reich has created in more than three decades, it is certainly is going to played. It was co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the London Symphony Orchestra, the San Francisco Symphony, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and the Baltic Sea Symphony.

Despite the quippy nature of his response, Reich and the L.A. Philharmonic have maintained a longstanding partnership that dates back to 1983 when William Kraft (the founder of Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group) performed an entire program of Reich’s music at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. It was a landmark concert that culminated with a performance of Drumming with Reich taking part as one the musicians. So, it was a nice connection of history that Kraft (now 95) could be in the audience for the premiere of Reich’s latest work.

It was probably unrealistic to think that at this point in his career Reich was going to present a work that was distinctly new or in some substantial way diverged from the path he’s been following for so long.

The form the work takes, Reich explained, is based on the concerto grosso. The soloists within the orchestra consist of paired flutes, oboes, clarinets, vibraphones, pianos, first and second violins, violas, and acoustic and electric bass. Their interplay propels the piece through five connected movements with the other members of the orchestra including four trumpets that provide momentum and the underlying harmonic landscape.

What Music for Ensemble and Orchestra displays most brilliantly is the work of a master craftsman who has developed his technique over the course of a lifetime: the piece shines like a multifaceted jewel.

The pillar of Reich’s compositions has always been a shifting sense of harmonic stasis. As stated by Reich, “the piece is in five movements, though the tempo never changes, only the note value of the constant pulse in the pianos.”

In this way the pulse in the pianos signals the beginning of each movement. Within that structure, as in the concerto grosso form, the movement’s melodic material ebbs and flows, passing from one instrument pairing to another. The instrumental contrasts are vivid as high voices in the winds float above the low strings and the thump of the electric bass line. At one point the mood almost takes on a shadowy film noir air of mystery. But on the whole, the atmosphere is one of bright, crisply punctuated Reichian familiarity.

Three Tales

On Saturday, Long Beach Opera offered the first of two performances of Three Tales, with music by Reich and visual accompaniment by Korot.

This gala performance at the Scottish Rite Temple’s Ernest Borgnine Theatre marked the opening of Long Beach Opera’s 40th season. It’s a remarkable achievement for a company that has always functioned as the loyal opposition and teetered more than once on the brink of financial collapse while consistently managing to push the creative envelope.

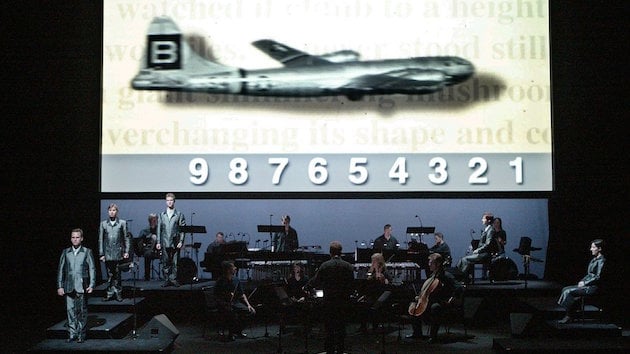

Three Tales, which premiered at the Vienna Festival in 2002, is one Reich’s documentary or “CNN operas,” a style that began in 1990 with The Cave. They picked up the nickname because of the way Reich’s music is integrated with Korot’s visual materials, which are drawn primarily from newsreel footage and contemporary interviews. The visuals are then overlaid, collaged, repeated, and fragmented in a manner that mirrors Reich’s formula of repeated figures and evolving rhythmic patterns.

On Saturday, Korot’s video was projected above an ensemble of 10 musicians and five singers (two sopranos and three tenors) under the precise leadership of LBO Artistic Director and Conductor Andreas Mitisek. And while Three Tales is only just over an hour in length, it delivers quite a punch.

Each of the tales represents a technologically significant moment in the 20th century, a moment that examines mankind’s ability to create and destroy. Tale one depicts the disastrous crash of the massive airship, Hindenburg (Titanic of the air), that collapsed into a fiery heap at a New Jersey naval station on May, 6, 1937, following its first ocean crossing. The second tale focuses on the obliteration of the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific and the forced removal of its peaceful native population, who were exiled so that the United States could test its latest nuclear bombs. Three Tales ends with a dialectical argument over the moral implications of bioengineering and artificial intelligence personified by, respectively, “Dolly,” the cloned sheep, and a robotic humanoid.

Reich immediately establishes a military tone to the Hindenburg tale set to the ra-ta-ta-tat of a marching snare drum. “It could have been a technical matter,” the three tenors (Thomas Segen, Robert Norman, William Grundler) intone as headlines proclaiming the disaster pulse across the screen.

We see the massive zeppelin with its swastika-painted tail collapse in a heap of molten fabric and iron. Then in flashbacks, we see its beginnings as a monumental feat of engineering and an ode to the (literally) rising power of the Third Reich. It soars over European cities that will soon to be conquered. It crosses the Atlantic for the first and last time, doomed to fall from the sky like a modern-day Icarus.

The second tale, Bikini Atoll, is by far the most painful and poignant. To the legato tones of lamenting strings, it depicts a modern parable of Paradise Lost as the peaceful islanders are displaced just so their Eden-like home can be transformed in a nanosecond into a radioactive wasteland, which, the video reminds us, is uninhabitable to this day.

As the countdown to Armageddon continues, we see the confused faces of the islanders juxtaposed with eager scientists and military personal who can’t wait to split the atom. And then there are the faces of doomed sheep and pigs about to sacrifice their lives in the name of atomic research. Rarely has Reich’s music reached the level of compassion that it attains in this tale.

In the final tale of “Dolly” the sheep, man literally plays God as the creator of life. Unfortunately, at this point the opera’s documentary nature becomes overburdened with a string of talking heads discussing the moral implication of cloning and the emergence of artificial intelligence. While the topic is worthy, the fragmented nature of the music and its amplified volume turns strident and relentless.

Throughout the performance the musicians and the vocal ensemble (which also included sopranos Kathryn Lillich and Alexandra Villareal Martinez) skillfully navigated the intricacies of Reich’s metric systems under the guidance of Mitisek.

In April Long Beach Opera will continue its minimalist exploration when the company presents Philip Glass’s In the Penal Colony.