The richness and diversity of the music of Samuel Barber is certainly known to record collectors, not so much to concert audiences who usually hear only the famous Adagio for Strings, and occasionally the Violin Concerto. That may be due to lingering judgments by the new music intelligentsia who considered Barber little more than a moss-backed Romantic when the hip thing was first neoclassicism, then serialism, and finally around the time of his death in 1981, minimalism. He knew it, and he suffered for it. Nevertheless, he produced some proud manifestos of who he was, some of which are included in the booklet from a pleasing new compilation of three contrasting Barber pieces from Gil Rose and his Boston Modern Orchestra Project (BMOP Sound, reviewed from a stream).

Knoxville: Summer of 1915 always makes a good leadoff piece to a Barber album. There is lots of lyrical nostalgia in this gorgeous rondo-shaped ramble through rose-colored thoughts of the America of 100 years ago, and I find it soothing to indulge in now and then. Kirsten Watson sports a sweet lyric soprano with a childlike quality appropriate to the material. In this chamber orchestra version, the BMOP is lean, sharply detailed, playful in the central episode, ardent in the nostalgic passages.

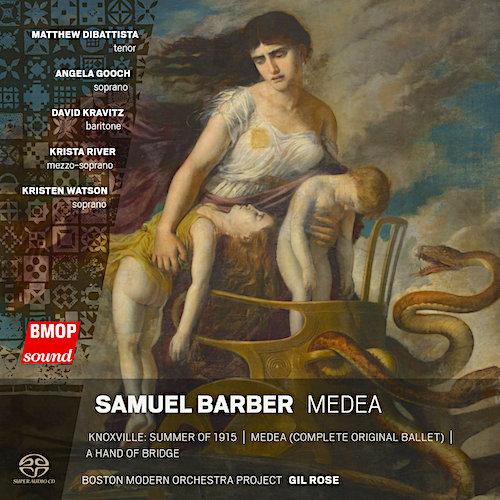

The ballet Medea, written for the Martha Graham Dance Company in 1945–1946, gets the headline on the album and presents a rather different side of Barber. It’s an often spiky, tough-minded score that foregoes long lyrical lines, proving that Barber’s range within tonality was wider than some would suspect.

Medea comes in three sizes — the original ballet for 13 instruments, a seven-part suite for full orchestra from 1947, and the much-shorter single-movement Medea’s Meditation and Dance of Vengeance from 1955 for an even bigger orchestra. Rose takes on the original, least-known version here. As you would expect, it has a different flavor than its successors: more astringent, more episodic, more obvious in its parallels to neoclassical Stravinsky, more potentially danceable — which Rose emphasizes. You do miss the extra firepower of a full orchestra when the inevitable climax comes and goes.

(For what it’s worth, a nearly similar 13-piece group, minus horn and oboe, was also used by Aaron Copland in his 1944 Martha Graham ballet Appalachian Spring; indeed, a short recurring passage in Medea seems to echo a similar one in the Copland work.)

Yet another facet of Barber, and the most interesting one here, is represented by A Hand of Bridge (1959), a comic micro-opera only 10 minutes in length that nevertheless conjures a world of emotions underneath its deliberately superficial surface. Rose and his cast (Angela Gooch, Krista River, Matthew DeBattista, David Kravitz) swing entirely into the period spirit of the piece set forth by the first of only three previous recordings of the piece that I know of (led by Vladimir Golschmann on a Vanguard LP from 1960 with two members of the original cast).

We’re in suburbia in the gray-flannel-suit 1950s. Two middle-class couples are going at their nightly bridge game accompanied by irreverent jazz piano and drums. In between deals, all are consumed by their inner thoughts as Barber waxes lyrically with the full ensemble. The lawyer pines away for his dream girl, while his wife is obsessed with the urge to buy a new hat. The stockbroker complains about his job and fantasizes about being a wealthy pasha in Palm Beach; his alienated wife laments about not being loved and not being able to love her dying mother.

Leonard Bernstein’s earlier Trouble in Tahiti covers remarkably similar territory, probing the emptiness of the American Dream while modeling the characters after people in their personal lives. Yet Barber and his trenchant librettist/partner Gian-Carlo Menotti do so with pinpoint concision, wit, and pathos, not wasting a second.

Spoiler alert: Barber and Menotti would never know that the stockbroker’s last word in the bridge game (and opera) accidentally name-checks a wealthy, real-life, Palm Beach pasha of the future. The word: “Trump.”