I must confess. I hated Rameau’s Platée when Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and the Mark Morris Dance Group performed it in Zellerbach Hall in 1998. To me, it unrepentantly mocked someone whose looks deviated widely from what society deems as alluring. True, that “someone” was a royal nymph rather than a human being. But the gods, goddesses, and underlings of Greek mythology embodied human strengths and weaknesses, and ultimately served as mirrors of ourselves. In the sense that Platée was you and me, I despised how she was treated.

Only now, with the passage of time, do I understand Platée as an engaging and inventive satire on people who lack even an iota of self-awareness. Perhaps it took the political developments of the past several years to make me finally accept that Archie Bunker lives on in 2022 and that self-awareness is far from a given in “civilized” society.

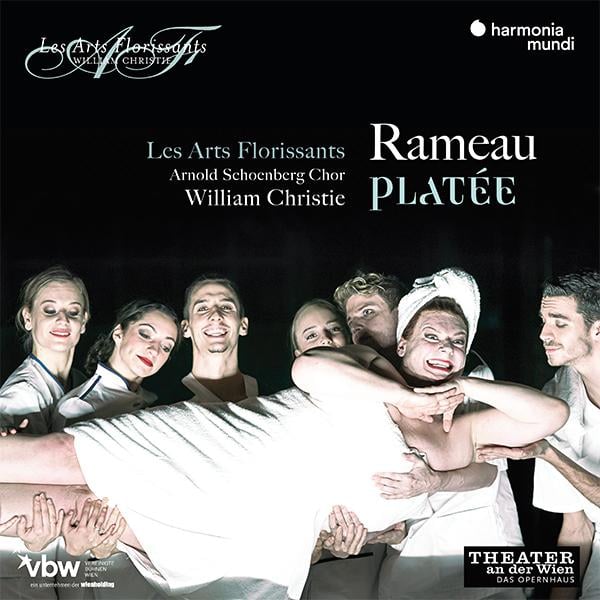

The latest audio recording of Rameau’s Platée (1745), which also exists on video, is a revival of a Robert Carsen production that was most recently staged at the Theater an der Wien in December 2020. Although it was simultaneously captured on video, it was never performed before a live audience due to the pandemic.

I actually found it easier to appreciate the work’s musical glories without the visual distractions of Carsen’s endlessly inventive ancient-meets-modern production. Playing Harmonia Mundi’s hi-resolution files[1] of Les Arts Florissants and the Arnold Schoenberg Choir, conducted by William Christie, it was hard not to fall in love with the charms and inventiveness of Rameau’s three-act-plus-prologue “comédie lyrique (ballet bouffon).” True, listening to numerous dance numbers on an audio-only recording can at times test the patience of someone who wants to get on with it. But the instrumentation in many of these dances is so delightful — take, for example, the characterful dances of the nymphs in Act 1, the graceful minuets, and the mellifluous dueting recorders in Act 3, Scene 3’s dance of dryads and satyrs — that the numerous interludes only add to the pleasure of it all.

The score abounds in instrumental felicities. Balancing the fabulous orchestral storm at the start of Act 1 — there are actually several storms, with their mock terror equally delightful — are the sounds of birds and other animals. The chorus even gets into the act, with a repeated “Quoi? Quoi?” (What? What?) that sounds like a flocking of honking geese. Time after time, Rameau seizes upon timbral contrast to amuse and delight. During a period when tragédie was the norm at the Académie Royale de Musique, he must have had a grand time composing Platée as part of a series of festive events at Versailles to mark the wedding of the Dauphin (the eldest son of the King of France) to a Spanish infanta (daughter of the Spanish monarch).

The opera, whose title female character was initially played in drag by the haute-contre (high tenor) Pierre Jélyotte, pushed the limits of what was considered acceptable at the time. As classically French as the vocal line, trills, and other embellishments may be, the characters themselves are anything but the expected epitome of elegance. Indeed, the singers on this recording, while highly skilled, rarely sound conventionally beautiful. Christie has previously recorded with highly refined, superbly voiced singers (the likes of Véronique Gens, Sandrine Piau, and Mark Padmore), but his cast for Platée is far more concerned with physical characterization and production values than ethereal vocal displays. Which is not to suggest that many of the arias, including La Folie’s “Aux langueurs d’Apollon” (The languors of Apollo) as delivered by Jeanine De Bique, are not expertly sung vocal showcases.

There is one performance that all vocal lovers will relish: Marcel Beekman’s brilliant Platée. From his first entrance, Beekman is vocally as well as physically over the top. Almost every line is exaggerated in some way. He sounds as ridiculous as he looks. Which is just as it should be, and undoubtedly was in 1745, when Jelyotte originated the female role.

Platée’s perfect foil, at least vocally, is Jupiter, played by the excellent bass Edwin Crossley-Mercer. As ridiculous as he may have appeared onstage, Crossley-Mercer’s straight man expertly balances Beekman’s excesses.

If you’re content with sub-par sound quality, you can find the entire recording on YouTube. For dessert, try this insightful interview with Beekman. What a perfect way to begin the New Year.

[1] The over two-hour recording is also available as a multi-disc CD set and can be streamed in CD quality (16/44.1) or hi-resolution from various streaming services.