When the world last heard from the San Diego Symphony (SDSO), they were in the middle of their first season with their new, dynamic, Venezuelan, El Sistema-trained music director Rafael Payare. At last on solid financial ground, they were poised to finally fulfill their potential, with a striking new outdoor performance venue ready to open that summer in July.

That was 17 months ago. You know what happened next. Everything got put on hold Mar. 12, 2020, and stayed on hold much longer than anyone expected. But time passed, the COVID-19 vaccines were made and distributed in sufficient numbers so that the SDSO decided the conditions was right to unveil their new facility. The time off had given them a window of opportunity to do more work on the new space; the budget, estimated at $42 million in the spring of 2020, had ballooned to $85 million by the time the first public concert took place.

And so the Rady Shell at Jacobs Park — heretofore simply referred to as the Shell — finally made its debut Friday night (Aug. 6), with Payare leading a sampler concert that I found to be more interesting and satisfying than most hall-opening programs I’ve attended. Still, the star of the show was the Shell, a bid by San Diego to create a southern alternative to Los Angeles’s nearly-century-old Hollywood Bowl — which it just might pull off.

On paper — or more concretely, in a scale model that I saw on display in the Copley lobby two years ago — the placement of the Shell just off the Embarcadero jutting out into San Diego Bay reminded me of the Sydney Opera House in Australia. That impression went by the wayside upon approaching the completed space. The Shell sits at the tip of a breakwater, surrounded on three sides by water, with a marina filling an adjacent inlet, and the massive San Diego Convention Center and downtown skyscrapers looming to the north. Another reference point that came to mind is San Francisco’s Oracle Park, which is perched alongside McCovey Cove where boaters park themselves in hope of retrieving splash hit balls. The folks at the SDSO are anticipating a similar kind of marine drop-ins here during concerts, catching musical notes (or maybe a flying baton) instead of home runs.

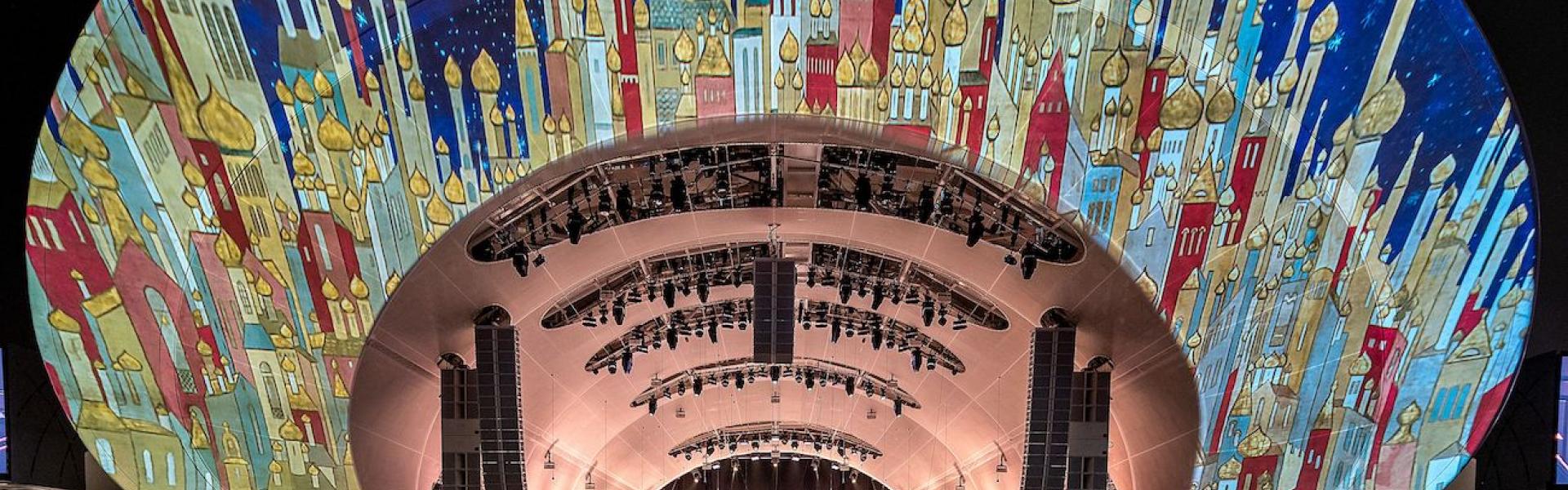

The 4,800-square-foot stage is crowned by a seashell-shaped structure (say that 10 times) covered with white PVC surfaces that are supposed to absorb sound to prevent echoes (once a notorious problem at Hollywood Bowl). Inside the shell is a Meyer Sound Constellation Acoustic system for the benefit of the musicians who can hear each other better, while an L-Acoustics amplification system projects the music out to the audience via six towers flanking the seating area. The chairs are portable, the capacity of the space variable up to 10,000 seats, with 3,500 to 4,500 seats being the probable norm for most occasions.

As heard at a rehearsal from a seat close to the lip of the stage, the sound was remarkably clear and natural. In the rear of the first section of seats during the concert, the sonics were not as natural-sounding yet well-balanced with a pleasingly robust bass. All the way in the back of the grounds, the basic balance was the same at a dimmer volume, but I could hear what sounded like time-delayed echo from a rear-firing speaker and a lot of ambient noise from the city.

Just as a Mason Bates composition led off Payare’s first concert as music director in 2019, another Bates piece — this time a world premiere commission Soundcheck in C Major — did the same for the Shell’s first event. It’s a likable, high-tech scherzo with electronics zapping away in surround sound from Bates and his laptops. Payare followed it up with Aldemaro Romero’s percolating Fuga con Pajarillo, a specialty of the house for both Payare and his Venezuelan colleague Gustavo Dudamel — and their dynamic approaches scarcely differ. Alisa Weilerstein’s cello was way up front in the mix of Saint-Saëns’s Cello Concerto No. 1, with cellist and conductor (who happen to be married to each other) maintaining a feverish pace.

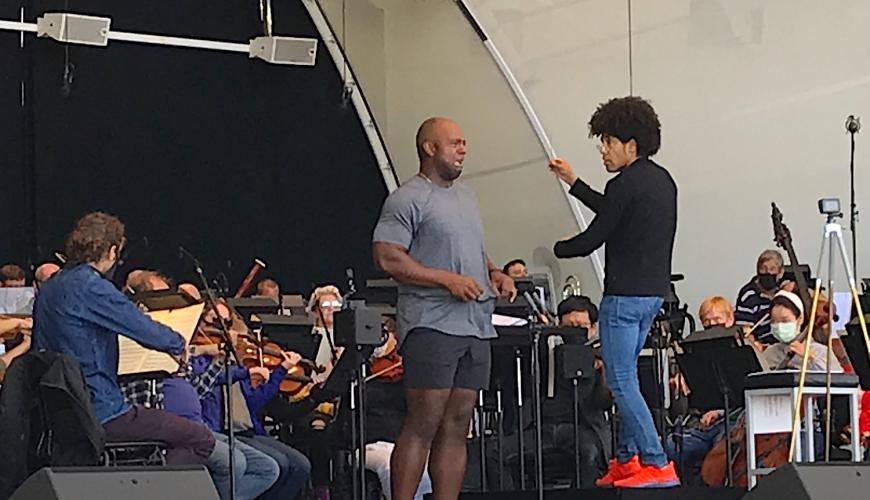

A true basso though billed as a bass-baritone, Ryan Speedo Green delivered a set that, intentionally or not, was a tribute to the great Ezio Pinza, doing powerful justice to selections right out of Pinza’s repertory from Gounod’s Faust, Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, Rossini’s The Barber of Seville and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific. Jean-Yves Thibaudet has performed Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue brilliantly in the past, but some of the polish came off the surface in some slapdash passages of a freewheeling rendition. After conservatively holding back during the first half of the concert, the lighting directors showed off their stuff in the second — blanketing the rim of the Shell with images of New York during the Roaring ’20s in Gershwin and Russian fairy tales in Stravinsky’s 1919 Firebird Suite, with fireworks over the bay following.

More impressions: The Rady Shell feels quite different from Hollywood Bowl in a significantly spatial way. Even though Bowl’s capacity is far larger, 17,500 or so, it feels hemmed in, protected in its canyon, almost completely isolated from its urban surroundings (save for aircraft). The Shell is the exact opposite — extraordinarily open to its environment, with the Coronado Bridge rising in a graceful arch to the rear, Coronado itself to the left across the water, and the San Diego skyline to the right. It’s also an outdoor place in a city that thrives and dotes on its outdoor activities; you can skate, bicycle, walk, or jog right up to it, with the San Diego Trolley only steps away. Given its location, its spectacular views, San Diego’s year-round temperate climate, its so-far promising sound quality, and assuming consistently enterprising programming, the Shell may well rival the Bowl as a go-to cultural destination.