There’s something magical about listening to spatialized electronic music in the dark. Time behaves a little unpredictably — long pieces don’t seem quite as strenuous, while short ones occupy a much greater span than anticipated. Deprived of visual distractions, my mind often made up its own, with sounds and movement taking up colorful shapes behind my closed eyes, evocative narratives and atmosphere arising even from the most austere and abstract selections.

The impeccable audio production quality and overall care given to the presentation of each selection by the San Francisco Tape Music Festival crew (happily in business since 1999) served as a kind of polish, smoothing out immediate difference in aesthetics between pieces from 50 years ago and much more recent productions.

The impeccable audio production quality and overall care given to the presentation of each selection by the San Francisco Tape Music Festival crew (happily in business since 1999) served as a kind of polish, smoothing out immediate difference in aesthetics between pieces from 50 years ago and much more recent productions.

Nothing sounded dated or obsolete, despite the vertiginous changes in technology that have occurred between the early days of the genre and the present. Unlike past iterations of the festival there was no portrait or thematic night this year: Classic pieces by Morton Subotnick, Eliane Radigue, Bernard Parmegiani, Anthony Gnazzo, James Tenney, François Bayle, Jon Appleton, and the Beatles (all composed or debuted in 1969) mingled with contributions from the U.S., Canada, Latin America, and Europe to create a varied, balanced, and convincing presentation.

I attended the free, late show on Saturday night, which attracted a mix of experimental music diehards and a few unsuspecting stragglers. The evening featured a pair of drone and process pieces in just intonation: Auric Blade by Kris Force and Glass by Larry Polansky. Both pieces created luminous spaces that greatly benefitted from the surround diffusion of the festival. Radigue’s Usral (a contraction of the French phrase for “slowed-down ultrasounds), which closed the night, served as a fitting bookend with its warm, ecstatic exploration of the “grains” of stretched-out feedback howls.

There was plenty of aesthetic contrast too, both successful and not. Some pieces, though cinematic, seemed to try a little too hard at securing a place in a future Dolby-THX demo reel. I enjoyed Raub Roy’s whimsical QTπ, with its more active beat-based rhythms, and Rob Hamilton’s touching tribute to Pauline Oliveros, One who lives near the olive tree, which tipped the hat to the late electronic-music pioneer through an exploration of gliding, close-tuned pitches, which eventually gave way to a crackling display of electrostatic fireworks.

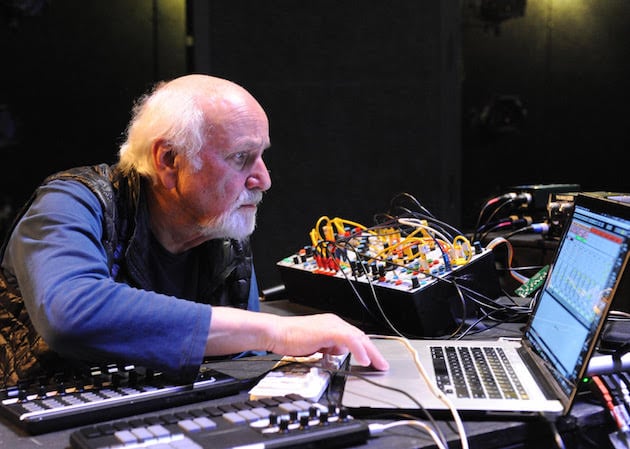

Sunday night presented a similarly structured program, culminating in Subotnick’s 30-minute Touch — a recording commissioned to showcase Columbia Records then state-of-the-art SQ quadraphonic system in 1969. Improvisatory and virtuosic in nature, it showcases Subotnick’s affinity with the Buchla modular system (electronic synthesizer instrument); resonant passagework reminiscent of muted gongs, the classic low-pass gate, and otherworldly marimbas was followed by a subdued and moving closing section, a kind of sweet heterophonic chorale from another world. The other historical pieces for the evening were Anthony Gnazzo’s Population Explosion — excerpted to a mere five minutes from the original “infinite” release on closed-groove loop, yet equally exhilarating in its simplicity and wit; and a collage of two of Parmegiani’s own classic/pop music collages, Du Pop À L’âne and Pop’éclectic, in which Stravinsky, Bartok, Messiaen, and Stockhausen (suitably in elektronische form) are pasted alongside the Doors and Frank Zappa for a delightful whirlwind of mid-century postmodernism.

The wildest sounds of the night came from Fernando Lopez-Lezcano’s Hot’n Cold, a 1991 composition exploring contradictory and ever-changing sonic states, including seemingly impossible resonance sweeps and frequency modulations that truly deserved the often misattributed characterization of “space sounds.” It was one of those rare treats in which I could say I had never heard anything quite like that before.

Such are the rewards of the San Francisco Tape Music Festival, which continues to offer uncompromising yet worthwhile explorations of electronic sound through time, geography, and practice. Kudos to the curating team of Joseph Anderson, Thom Blum, Cliff Caruthers, Kent Jolly, Maggi Payne, and Matt Ingalls, who might have broken the second or third rule of the festival when he joined his own piece with a live improvisation on violin and clarinet — the tape-music police have been alerted and decided to let him off with a warning, but just this once.