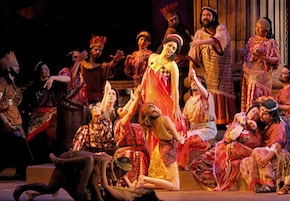

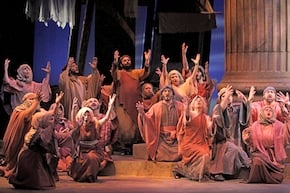

Photos by Otak Jump

José Luis Moscovich and West Bay Opera have done it again. They are offering a big, colorful, complex production of truly (perhaps bizarrely) grand opera. Successfully.

Camille Saint-Saëns’ 1877 Samson et Dalila is an opera you expect to see in the mega-houses of Paris and New York, not in the Palo Alto company’s Lucie Stern Theatre.

Not the full French romantic/melodramatic treatment of Chapter 16 of the Book of Judges, complete with the destruction of the Philistines’ Temple of Dagon, on a stage of 26 x 36 x 16 feet. (For comparison, the region’s last Samson took place on the War Memorial stage, which is 52 x 64 x 116 feet.) Why, that’s almost like slaying an entire army with only the jawbone of an ass — one of Samson’s previous accomplishments.

Related Articles

Purcell and Falla Die Double Deaths

May 20, 2011

West Bay Opera Turns on the Glam

May 21, 2010

Moscovich’s accomplishments in just five years of his intendancy include daring programming, rallying a small company painfully from budget to budget, excellent casting, surprising production values, new translations for supertitles, and outstanding musical leadership.

If you’re surprised to see Biblical splendor, a pagan orgy, and “the unpermitted demolition of a historic building” (in the program description by Moscovich, who is also an urban planner and transportation engineer), consider that he has already produced in the same 400-seat theater: Turandot, La forza del destino, Der Freischütz, and The Flying Dutchman — yes, the one by Wagner. Next up: Don Giovanni and Aida. The man does not think small.

“Dungeons & Dagons” notwithstanding, the biggest challenge for West Bay’s current adventure is to find the right singers for the principal roles. It’s done. Samson, who has his work cut out for him even if Saint-Saëns didn’t give him a big aria (against three for Dalila), is Percy Martinez, the young Peruvian tenor heard and praised here before. His is a lyrical “French tenor,” but with the right hint of steel under it. His diction and legato were exemplary.

In the true title role, Cybele Gouverneur makes an impressive West Bay debut. The Venezuelan mezzo, known for her performances in San Jose and San Francisco (where she will sing Mercedes in the upcoming family matinees of Carmen), has a big, velvety voice, which she projects expertly to fill the house. Chances are it could be a much larger house than this, and the effect would be the same. An up-and-coming major talent.

David Cox made a fine contribution as the High Priest of Dagon (aka Dalila’s father), while Matthew Lovell and Carlos Aguilar did well as the Satrap (governor) of Gaza and an Old Hebrew, respectively.

Bruce Olstad’s large community chorus was on its best behavior, singing and acting variously as Hebrew slaves, priestesses of Dagon, Philistines, et al. Bruno Augusto, Katie Gaydos, and Daiane Lopes de Silva of the Kunst-Stoff Dance Company performed choreography by Yannis Adoniou. And the supernumeraries included Walter Li as the Angel of God.

Once again, it’s astonishing to see more than two dozen people on that stage, especially in the midst of orgies, human sacrifice, and the other space-requiring activities. Directing traffic and action, expertly, was recent Merola graduate Ragnar Conde. Jean-Francois Revon once again provided ingenious sets looming large, and Abra Berman’s costumes were outstanding, very much in the major-house category.

Moscovich’s conducting started more tentatively than usual, and until the performance really caught fire with the big Act 2 duet (which was terrific), he mostly maintained a cautiously slow tempo. It might have been a wise decision, because on this outing the orchestra was experiencing problems, especially the strings, where individual instruments stood out occasionally (and not in a good way). Woodwinds and brass fared better, and in the climactic moments it all came together.