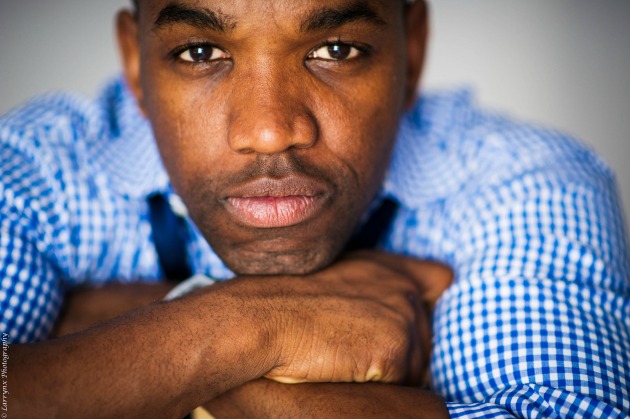

As anyone who attended this year’s Opera in the Park can attest, tenor Lawrence Brownlee, 43, is at the top of his game. A high tenor who can summon uncommon weight and gravitas in the center of his tone, Brownlee first garnered attention when he won the Metropolitan Opera Auditions in 2001. A year later he made his professional debut at Virginia Opera in what has become one of his signature roles, Count Almaviva in Il Barbiere di Siviglia. He also sang at La Scala, Milan that year.

In 2006, Brownlee won both the Richard Tucker Award and Marian Anderson Award. One year later came his Metropolitan Opera debut, with appearances in most major European and American houses before and after.

Surprisingly, it has taken until now for Brownlee to reach the stage of the War Memorial Opera House. If his two performances in Sharon Meadow on September 11 are any indication – the last of his nine high Cs in the famous tenor aria from Donizetti’s La Fille du Régiment rang for an astounding number of seconds, and he caressed the phrases of the spiritual, “All Night, All Day,” with heart-seizing tenderness and beauty – his forthcoming stint in Donizetti’s Don Pasquale (September 28 – October 15) could bring down the house.

On September 8, Brownlee and I spent close to an hour together at the War Memorial, Opera House. We began with the arc of his career.

Do you wish you had started earlier?

I first made my professional debut at age 27 or 28 [actually, at age 29 going on 30], after my body had 10 years to percolate and catch up with my voice. Some voices are bigger than the bodies that house them, and bigger than people have the capacity to control. Starting out a little later gave me the opportunity to know my body and my voice.

In my opinion, the changes that happen to a classical voice between 18 and 28 are much more significant than the changes that happens between 28 and 38. The natural maturity in the voice is essential for singing certain roles. Currently I’m being cast for roles three to five years down the road. Some people accept roles in advance with the hope that their voice will be ready by then, and have the maturity, weight, and mastery necessary.

Between 2001 and 2010, when I won the Tucker [actually, 2006], I had the chance to sing in a lot of places in Europe. I was second cast to Juan Diego Florez at my La Scala debut in 2002, and sang leading roles in some of the mid-level houses in Genova, Bologna, Toulouse, Lausanne, all the while going back to La Scala and then to Berlin and Hamburg. I built my repertoire and became more comfortable onstage. Then, in 2007, I made my Met debut.

How has your voice changed in the past 15 years?

I let my voice decide what was right. Now I can sing things I couldn’t sing 10 years ago. My voice isn’t necessarily bigger, but some of the colors, some of the nuances have changed. It’s a more mature, seasoned, and interesting sound. The top was always there, but I now have a good amount of color in the lower register, and the middle and bottom are more dependable.

What roles might you not have considered in 2002 that you would consider now?

I’m considering some of the lighter French things that I wouldn’t have sung in 2002, when I sang a fairly limited repertoire of The Barber of Seville and La Cenerentola. But now people are asking me if I want to sing La Favorite, Pearl Fishers, and even Damnation du Faust. I’m in discussion with my agent now about what to book down the road.

Are you able to do the all dynamic and tonal shading that are so central to bel canto singing and still project in large houses, or do you have to decide what you do depending upon the size and acoustics of a particular house?

My teacher, Costanza Cuccaro, whom I haven’t seen in a while, always said, “Your voice is your voice. Use it efficiently. You want to sing to the back of the theater. But some are extremely large, and not acoustically designed for your repertoire. In that case, you have to bring the people in. Make them lean into you. If they lean into you, and you tickle their fancy with the shadings, subtlety, and coloring that are true bel canto, that’s the only thing that matters.”

My voice is set up to do primarily bel canto: Donizetti, Rossini, and Bellini. But it’s about more than the pyrotechnics, and not all theaters are set up for that. I need to make a case for voices like mine singing in theaters that are not particularly favorable to bel canto singing.

Some people have natural, huge voices. But some who don’t have huge voices have such a natural point – squillo – in their voice that it carries through. Juan Diego Flórez’s voice is very squillante, but he doesn’t have a large voice. People always compare us, and say that my voice is bigger, but his has more squillo. I would say that’s probably accurate.

Let’s talk about Don Pasquale and its challenges.

People don’t realize that the second act aria, “Cerchero lontana terra” is so difficult. You gotta pace yourself well. A lot of people know it for its trumpet solo, but it’s a beautiful aria. The cabaletta isn’t as florid as a lot of the things I do, but the tessitura is fairly high. You have to engage with that click that’s a little bit higher. It ends with my highest note in the opera, a C sharp.

As in many Donizetti operas, the tenor (Ernesto) is one of the leading characters, but he’s not the central focus. Nemorino in L’Elisir d’Amore is, but even with Tonio’s nine-high-Cs aria in Daughter of the Regiment, the focus isn’t mainly on him.

How do you feel about the plot of Don Pasquale? They certainly make a lot of fun of the title character because he’s old.

Alessandro Corbelli, whom I’ve worked many times with, says in operas and roles like this, you have to really be invested in the person. It’s not a caricature. Don Pasquale is a real person who really thinks this way, which makes it even funnier, I think.

I love the plot. I like that he’s trying to force me, his nephew, to get married so I can be his heir. I’m the only person he can possibly have as an heir, and he wants to get his way.

The real plot is that he’s trying to strong arm me, and I’m resisting because I’m in love. So Malatesta sets him up with Norina, the girl I love, which interests Don Pasquale because it means he can leave his money to his wife. When he sees her, she seems docile and mild as well as gorgeous. This makes him believe that they can really marry and his problems will be solved.

What do you do if one of your colleagues treats their role as a caricature?

Of course you have to meld. When colleagues have a different idea than I, I feel it’s the stage director’s job to make sure we’re all together. Sometimes ideas change when directors discover that someone’s comic timing works differently than they had planned, and we find something we can all agree upon.

I know San Francisco’s cast, and know we will work as a unit. None of us is so full of ego that we can’t change, or so married to certain ideas that we can’t be flexible.

I arrive trying to be a blank slate, and complement the other performers’ conception. For example, when I contracted to do [Rossini’s Le Comte] Ory in Seattle, they had in mind the absolutely brilliant production that I did with Cecilia Bartoli, and that I loved. But they changed to a new production, and I had to be a blank slate. I let myself go all the way there, and grasp the essence of what the director was trying to create. [It was a fabulous production, and Brownlee sang sensationally.]

How do you approach embellishment and interpolated high notes in the bel canto roles of Donizetti, Bellini, and Rossini?

Rossini specifically wrote in embellishments and ornamentation, and expected people to sing his music differently each time. His strophic writing style made that possible. Donizetti started to take some of that stuff out. It wasn’t as much about the pyrotechnics as about the legato, the lushness, and rubato.

I also think there is a place for tradition. I don’t think Puccini wrote a high C near the end of “Che gelida manina” in La Bohème, but everyone wants to hear it. People come to the Met from afar to hear that high C, the high E-flat in Lucia, or, if you can do it, the high F in I Puritani. They want to hear these notes because tradition says these notes are what make memorable evenings and stars. So I don’t like to be totally tied down. I like to believe that if Puccini or Verdi were here today, they would say, “You know what? That high note does work, and is in good taste.”

I’ve worked with some living composers who say, when I try a high note, “You know, that note does work well. Let’s put it in the score.”

So Rossini expected interpolation more than Donizetti?

Yes. But there is a place in live theater to create these moments that make goose bumps. I just did Puritani in Zurich. I love my Italian colleagues, but they always have opinions. This Italian bass said to me, “Oh, you don’t have to ty to sing this high F. It’s never pretty.” He wanted to protect me in case something went wrong.

I said “fine,” and then sang the high F every show. I spoke to the conductor, Fabio Luisi, about doing it, and he said, “If you have it, let’s try it. It’s your decision either way.” I was prepared to do it unless I didn’t have the wherewithal on a particular night. But by the beginning of Act III, I always knew if I had it or not,

I didn’t do it out of ego, but rather to give people a special experience. For people coming from China, Berlin, or Zurich to hear the performance, the fact they could experience me so invested in the performance that I’d venture a high F meant a great deal.

You seemed to love all the physicality and movement in Seattle’s Count Ory.

The direction was so good that there were times we were struggling to hold it together onstage, it was so funny. And this production is also extremely physical.

My involvement in music started when I was 15, in a high school show choir that required equal singing and dancing. After that, for four summers, I worked as a singer/dancer in an amusement park. I also have a big hobby in salsa dancing, and I play tennis, table tennis, and other things. I welcome movement. I want to be a stage animal.

I always allow myself to be challenged. Any challenge for me is an opportunity to unlock potential. My comfortable changes, so I like to surprise myself, challenge myself, and go with the vision.

Before we run out of time, let’s talk about – I don’t know how else to put it – the “Black Thing.” At this point, do you run into shit because of your race?

It’s not overt. I run into it, but it’s just people’s ideas. Sometimes opera theaters are like constituencies. They know the people that are coming, they know they’re in a certain place where certain things are not necessarily accepted.

Of course, the President of this country is a multiracial man who identifies as Black. He’s very well-spoken, very intelligent, handsome… all those great things. So I think that people are now seeing and know – even the people who are kicking and screaming and want to “Make America Great Again” – that this country is a multicultural melting pot. They don’t want to, but I think the Republican Party will continue to deteriorate if they don’t accept it.

It’s the spoken and the unspoken: There are people out there who think a gay person is not as good as a straight person, that a woman is not as good as a man, that a black person is not as good as a white person … They have this deep-seated, unspoken stuff.

I’ve never used my race to think that I would do less in this business. I had a teacher early on who told me that I have to be better than the average guy just to be considered equal, and then I have to have something special. I want people to say that something I do is not the norm, but instead special. It’s going to give me, a short African-American who is less round now than before, a fighting chance to do what I feel I was born to do.

Some people say, “He’s not right for the part. He’s too this or that. We have a different person in mind. The person we have cast is different. The height differential won’t work. We want more of a playboy look.” There are a number of things that people can say that could be perceived as code for, “We don’t necessarily want a black man in this role.”

It’s my job to try to change their mind. There are a lot of times that I think people have been won over, or hadn’t thought that I would be successful. Many people have told me that they didn’t think that I would be successful because I’m a Black man.

Is this sometimes exhausting?

No. Not at all. I saw this movie, A Few Good Men with Cuba Gooding, Jr. He was a Navy diver or Navy something. He wanted to be the absolute highest rank in it. Someone asked him, “Why do you want this so bad?”

He replied, “Because they told me I couldn’t have it.” So to all the naysayers along the way who didn’t believe in me, my success is my reward. I don’t want to flaunt it, or taunt people by declaring that I proved them wrong. But I really want to show people that I was committed hard enough to hopefully make this dream a reality, and something I should be doing.