It was succinctly called “Noon to Midnight.”

On Oct. 1, 2016, for 12 continuous hours, a succession of wide-ranging contemporary music concerts ebbed, flowed, and overlapped throughout Walt Disney Concert Hall: its auditorium, its lobbies, its stairways, its gardens, and eventually out onto the street.

Presented by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, as part of its Green Umbrella series, this marathon of musical performances and multistage logistics attracted an enormous — and in many cases younger — audience. Many stayed for the entire 12 hours.

There were performances by the L.A. Phil. Bass Quintet, the Los Angeles Percussion Quartet, wild Up, Piano Spheres, gnarwhallaby, the St. Lawrence String Quartet, wasteland, the USC Percussion Ensemble, Monday Evening Concerts, the USC Percussion Ensemble, Jacaranda, and The Industry (under the direction of Yuval Sharon), which unveiled a billowing musical-sculpture installation called “Nimbus.”

“Noon to Midnight,” says Deborah Borda, the L.A. Philharmonic’s President and CEO, “was the embodiment of what we see as the future of the L.A. Phil. as a community organization, a future in which larger organizations find ways to partner with smaller, more nimble organizations in ways that everyone benefits. In many cities, I find, there is an antagonistic relationship between the smaller groups and the symphony orchestra — the 10,000-pound gorilla. Here in Los Angeles, we have tried to form a real working relationship.”

Those 12 hours were a vibrant demonstration of how active the new music scene has become in Los Angeles. We are in the midst of a golden age. But there is also a downside, and it is a challenging reality.

A month after the last notes of “Noon to Midnight” had faded away, patrons began to receive a flood of end-of-the-year requests for tax-deductible financial support. Whether they were major presenters like the L.A. Phil. or small independent presenters like Jacaranda, the message was the same — PLEASE DONATE.

According to Patrick Scott, co-founder of Jacaranda, the expanding landscape for new music in Los Angeles, while a boon for the city, is putting a strain on patrons, donors, and commissioners of new works.

“There’s so much going on that there are no longer any conflict-free weekends, which poses a challenge [when] contracting musicians and scheduling concerts. We’re also finding that patrons are being asked to support more and more organizations, which makes it difficult to project our budget.”

In 2016, Scott said, Jacaranda’s anticipated year-end donations declined, not because of any lack of performance quality or even attendance, but because the organization’s donor base was being asked to support any number of equally worthy organizations.

As one donor couple put it simply, “We can only give so much, and we have to make choices.”

“Traditionally, you can count on 30–40 percent of your revenue coming from ticket sales,” Scott explained. The rest has to come from other sources. We are also entering a postelection era where all our assumptions about what people care about have to be questioned. We are going to need to develop new models.”

As Deborah Borda observed, “There’s no one kind of donor. And part of the art of fundraising is knowing that every donor is different. Some like to be much more involved. Some like to be hands-off. Some like a lot of acknowledgment. Some prefer to be anonymous. The art of it is figuring out what works with that particular donor in your particular organization. A gift of $10,000 to Jacaranda is major, whereas the Philharmonic (with its multimillion-dollar budget) has to generate so many of those, every year.”

The roots of support for contemporary music in Los Angeles run deep, beginning in 1939 when Frances Mullen Yates, a concert pianist, and her husband, Peter, co-founded the “Evenings on the Roof.” At their home in Silver Lake, the couple offered some of the first local performances of works by Ives, Schoenberg, Bartok, and, later, a young Pierre Boulez. The Monday Evening Concert series, the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s New Music Group (founded by William Craft), and the Ojai Music Festival followed.

But it was Betty Freeman who became known as the “Patron Saint of Patrons” in Los Angeles. Freeman, who died in 2009 at the age of 89, over a period of four decades provided some 400 grants and commissions to a host of composers including Harry Partch, John Cage, Conlon Nancarrow, Philip Glass, Robert Wilson, Steve Reich, John Adams. The list is long.

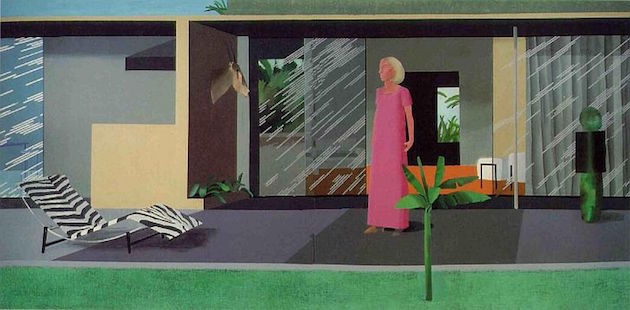

In collaboration with the late music critic, Alan Rich, Freeman and her pasta-cooking husband, the gregarious Italian sculptor, Franco Assetto, maintained a long-running series of musicales. Several times a year, composers spoke about and presented performances of their work at Freeman’s spacious Beverly Hills home amid her remarkable collection of modern art: canvasses by Sam Francis, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and David Hockney’s homage to Betty, “Portrait of a Beverly Hills Housewife.”

The musicales were a very special gathering place where composers, musicians, journalists, arts administrators, patrons and would-be patrons could gather. Opinionated and contrary though she was, Betty Freeman paved the way for a new generation of composers and fostered a new generation of patrons.

Raulee Marcus, a former advertising executive, is a member of the post-Freeman generation who are supporting organizations and commissioning new works. As such, her financial support is highly sought after and competed for.

“There are many more organizations today in Los Angeles, whether they are presenters or performers or composers, that are doing exciting work and getting receptivity from audiences,” she observed sitting in the living room of her 11th-floor downtown loft. “But at the same time, because there are so many more, it’s harder to dial for dollars.

“One of the things I’ve been thinking a lot about,” she said, “is how to empower organizations to work together so that you get the top skills of one combined with the top skills of another. For example, Patrick Scott of Jacaranda is a master of programming, but he’s never been able to have enough donor money to offer a second set of performances, which would make his organization stronger. I think the answer is to help organizations pool their talents and their resources.”

Marcus cites as an example Los Angeles Opera’s newly formed collaboration with New York-based Beth Morrison Projects. It’s a partnership allows L.A. Opera to present cutting-edge work in a small alternative venue, the Cal Arts’ REDCAT theater beneath Disney Hall. These are works that would never fit or be economically viable at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. The programs also tend to attract younger audiences. A major exception was the company’s highly successful staging of Phillip Glass’s opera, Akhnaten.

When it comes to commissioning new compositions, there are two essential models, hands-on, hands-off. Marcus sees herself as the former.

“I want to get to know the composers as well as the performers and the presenters,” she explains. “I want to feel like I’m part of their community and they’re part of my community.”

Which raises a tricky issue. As Deborah Borda pointed out, a $10,000 donation to a small organization or a rising composer carries a lot more weight than a similar donation to the L.A. Phil. What can a patron expect, or demand, along with their check? For Borda the answer is simple, nothing beyond thanks, the pleasure the patron gets from the act of giving, and (if desired) credit in the printed program. It’s a tricky balancing act that has been going on as long as there have been artists and patrons.

“I’m not a micromanager,” Marcus attests. “I believe my role is to get the most creativity out of the process. I’m not there to tell someone how to do what they already know how to do. Where I can help is as a facilitator on the business/marketing side. I’m not a musician. I’m not a composer.”

Under the leadership of music director, Jeffrey Kahane, the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra made the commissioning of new works and its Composer-in-Residence program a priority. And in 2001 the company introduced a program to support new commissions, called “Sound Investments.” This is how the program is promoted:

Have you ever listened to a favorite symphony or concerto and wondered what life experiences and inspiration shaped the composer’s ideas, how the orchestra players reacted upon first reading the new score — or how the composer felt as musicians finally gave sonic life to notes on paper? When you commission a new work of music through Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra’s Sound Investment program, you can get your own answers, straight from the composer’s mouth.

Each season, the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra commissions and premieres a new piece of music composed especially to suit its unparalleled musical talents. Creating a legacy in music, members of Sound Investment each contribute $300 (or more) toward the composer’s fee and costs of the premiere concerts. As an “investor,” you and a guest will be invited to a series of intimate salons during the season where you can meet the composer, hear excerpts of the score-in-progress and attend a full orchestral rehearsal of the completed work. Along the way, you’ll gain an insider’s view of the creative process through lively and thought-provoking conversations with the composer. Membership also includes a pair of tickets to a premiere performance of the work you helped create and your name inscribed on the dedication page of the printed score.

To be continued.