Hailed by Opera Magazine as having a “heroically shining tone of exceptional clarity and precision,” African-American tenor Russell Thomas, at 44, is making his operatic mark both on and off the stage. Recently appointed by Los Angeles Opera as artist-in-residence through the end of the organization’s 2023–2024 season (succeeding composer/conductor Matthew Aucoin), Thomas, who studied at Miami’s New World School of the Arts, is no stranger to the City of Angels.

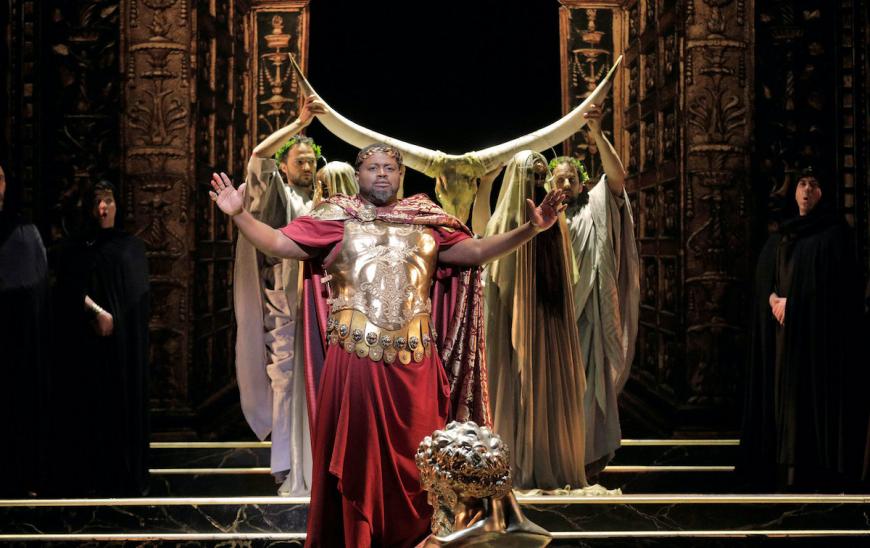

Having performed in LAO’s Norma in 2015, Tosca in 2017 and as the titular role in The Clemency of Titus in 2018, Thomas also worked with the LA Philharmonic that year in The Song of the Earth, under the baton of Music Director Gustavo Dudamel, who again led the tenor in a production of Otello at the Hollywood Bowl that summer. Indeed, the musician also has a global presence, having performing at, among other illustrious venues, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Oper Frankfurt, and at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden.

Thomas’s vocal credits also include singing the role of Ismaele in Verdi’s Nabucco at the Metropolitan Opera in 2017, while his portrayal in Clemency in a new Peter Sellars production that same year drew praise from The New Yorker’s Alex Ross, who wrote, “Thomas’s penetrating tenor, which has lately acquired richness and heft, anchored the evening.”

And on June 6, the musician returns to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, when LAO presents Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex — the company’s first public performance in more than a year — for a socially distanced production in accordance with safety protocols. The highly stylized 1927 work meshes well with COVID-19 restrictions, as the composer had requested that it be staged with minimal movement.

Music Director James Conlon conducts the 50-minute, intermissionless performance, which will also feature projected animations created by Manual Cinema, an Emmy Award-winning performance collective, design studio and film/video production company. Famed actor Stephen Fry will make his LAO debut (via audio recording) as the Narrator, and Matthew Diamond is directing the streamed presentation. The live performance is sold out, but the show will be available for viewing June 17. Visit the LAO website to sign up for more information about the digital stream.

Catching up with Thomas by phone from his home in Atlanta, I had the pleasure of chatting with him on a range of topics — from his relationships with conductors to how opera will have changed after the pandemic and his newly minted position with LAO.

Have you sung Oedipus before, and what about having worked with any of the cast members — J’Nai Bridges as Jocasta and Morris Robinson as Tiresias?

I have sung Oedipus before, about 12 years ago with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and James Levine conducting, but I never had a chance to sing it again. I will do it in December, though, with Esa-Pekka Salonen somewhere in Europe.

I know J’Nai very well, but we’ve only done a concert where we didn’t sing anything together. With Morris, we’ve known each other for 20 years and have sung together, so I’m happy to be working with him again.

Someone else you’ve frequently worked with is James Conlon. What makes for a good collaboration with a conductor?

I don’t know if there’s a secret to what makes a good working relationship with a conductor, but as with anything, having an openness about the experience and being open to ideas is part of it. I come to this [Stravinsky] piece with an experience and my own ideas [as does] the conductor, but everyone being a bit flexible will usually make for a rewarding experience, at least that’s been my way of getting along. And with a willingness to try — vocally, musically, dramatically — we usually can get a great performance.

The worst thing is for someone to come in and be stuck in their own ways — and it’s still that way with some conductors. I find if they have respect for a singer who comes in with clear, defined ideas — and a reason for them, not because they’ve heard it on a recording — I find that most conductors would be willing to at least try it. They might not like it, but that’s the attitude we have to have, in life and in art.

What are your thoughts on being named artist-in-residence with LA Opera — and what are some of the projects on tap, such as the Russell Thomas Young Artists in Training, which begins in August?

Being awarded this title, given this opportunity, is huge for me. I have a desire in my post-singer life to run an opera company the way Plácido [Domingo] did it. I want to get the experience [and] the way this appointment works, the company and all of their department heads will train me how to do those jobs in a meaningful way in the next three years.

The most exciting project is the academy for young singers, because being a singer is so expensive and I was lucky when I was younger that people invested their time and energy in me. Setting up a program like this, we can find and nurture young singers through the early stages of their careers who wouldn’t be able to afford it. I couldn’t afford it when I was 16 or 17, when singing lessons could cost $50–75. an hour, so bringing in five young singers could be life-changing for one of them or all of them.

We’re doing auditions — people are submitting videos — and we’re looking for [underserved] high school students. We’re offering small stipends each week and they also make a little bit of money in the process, so they don’t have to worry about taking them away from a part-time job.

You’re also mounting a virtual training program for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) students, offering direction on audition techniques, repertory, and the nuts and bolts of how to build a career.

This has not been done before, but Fort Worth Opera and soprano Jennifer Rowley did an online master class during COVID-19, and that’s what we’re modeling it off of. There will be 10 singers and 10 sessions over six months. The singers will prerecord their music for that session or they will sing live if they have the ability to do that. We’re coaching them to do their arias, giving them advice on how to make it better. At the same time, we’re teaching them about the different aspects of an opera house that might resonate with them. We’ll probably find some great singers and get them to network with people on a higher level of opera.

Lack of diversity has been an issue with many cultural institutions, so this is your way of making much-needed inroads.

Yes, it’s important that opera companies expand the future of opera and a program like this will do that. It gets singers on the younger end and kids in college who usually don’t get taken seriously, interested. Because they don’t go to a traditional conservatory, a program like this will help the opera world discover new voices.

I went to a predominantly white institution, a conservatory with a traditional operatic track. HBCUs don’t have that, but I’m hoping this kind of program will change that. The only thing we can do is try to move the needle forward to a more diverse stage, a more diverse back office, and a more diverse audience.

As an African-American singer, did you find it more difficult to break into opera, or was that not a factor?

I think it was a factor. I don’t know about breaking in [as] I experienced some very overt racist things. But I was lucky because I had people in my corner. My mentor, Elaine Rinaldi, taught me arias and roles in the younger part of my life and people gave me money so I didn’t have to worry. Now I can pour that support into other young artists — and not just Black artists. But I think Blacks have a harder time, and I take this privilege that I have been granted very seriously and try to help as much as I can.

Now that we’re coming out of the pandemic, how do you think opera will have changed and were you seeing audiences getting younger, staying the same or becoming grayer, so to speak?

The audiences in L.A. for Titus were very young, and it wasn’t like some new modern production. I hate to say it, but the fact that they put these banners all around L.A. with a Black face on the banners made people interested in what was going on in that city. You saw my face and the soprano’s face [Guanqun Yu] all over. It was so amazing — and I met people after the show who told me that was their first time seeing opera.

People are doing something right in L.A. that’s getting audiences — both youthful and gray hairs. There’s a balance and it’s working. They’re putting on good work in the Latino community and I hope with my presence we can go more into Watts and the Black communities, but what’s happening at the Dorothy Chandler is they’ve done a great job.

Post-COVID I think it’s going to be huge for opera companies to not only remain relevant, but to find ways to save money. What COVID has shown us is you don’t have to go to Boston to experience Boston Lyric Opera, you can experience it from the comfort of home. We have to become ambassadors, not just in Los Angeles or Atlanta, but all over the world, and COVID has shown us how to do that in a very meaningful way.

I’m also excited about the kinds of interactive, multimedia things that I think are the wave of the future, without big, bulky sets, but paring opera down with video projections. For live performances, it doesn’t have to be a giant Zeffirelli production or cost millions of dollars. And even though they were written hundreds of years ago, the subject matters are relevant. Women are still being assaulted by powerful men [like in] Tosca.

No matter how you look at it, there’s nothing in an opera that is not relevant. We have to bring those stories forward, because they’re as timely today as when they were written. We don’t do a good enough job with that [because] we’re trying to make opera young and hip. It doesn’t need that — it needs to tell stories. We just do it in a very heightened and emotional way — it’s big and loud and it’s our way of telling relevant stories.