Every time Aynur opens her mouth to sing in public, she rebukes a government that casts her as a separatist.

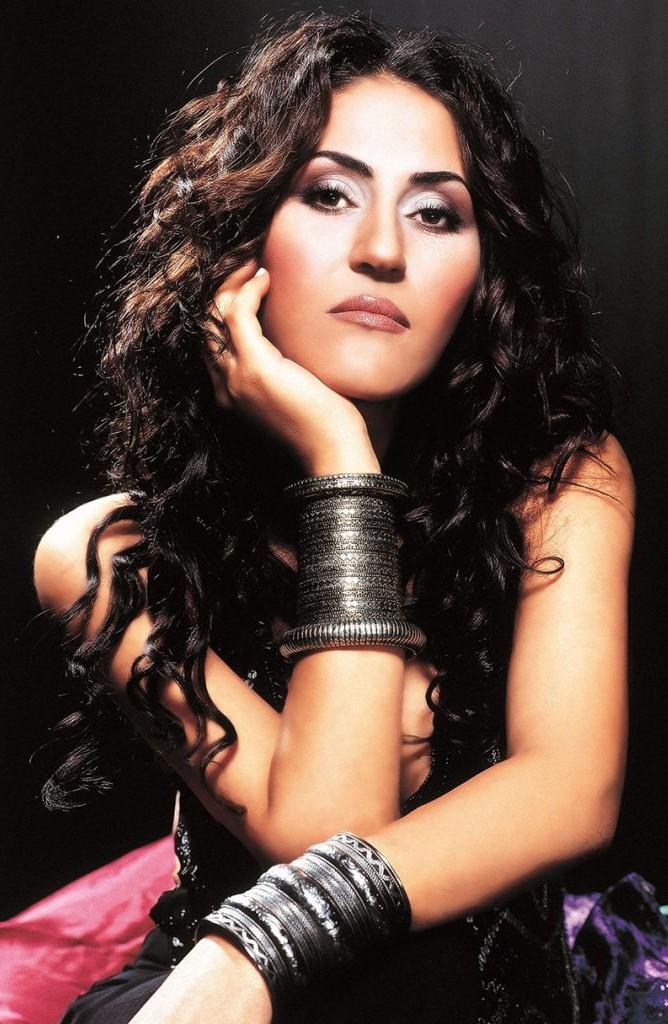

It’s a label she rejects and a role she didn’t seek, but a campaign of vilification by Turkish hard-liners has turned her into the world’s most visible Kurdish artist. Now based in Amsterdam because a rising tide of invective made living and performing in Turkey untenable, Aynur possesses a voice and musical vision that is fully equal to her renown, even as she tries to keep the focus squarely on her artistry rather than politics.

She made her Bay Area debut at Fort Mason’s Cowell Theater in 2006 as part of the San Francisco World Music Festival’s “Voices of Kurdistan” concert series, a packed weekend program featuring traditional and newly composed Kurdish music, poetry, and dance. A nine-city U.S. tour brings her back to the Cowell Theater on Saturday, April 22 for only her third performance in the Bay Area.

Presented by Diaspora Arts Connection, the Bay Area nonprofit known for showcasing women artists from Iran and neighboring countries where female voices are often suppressed, Aynur is touring with a quartet that includes Macedonian clarinet virtuoso Ismail Lumanovski, who’s often performed in the Bay Area with the Balkan brass band Inspector Gadje. Aynur’s group also features Grammy Award-winning pianist Kevin Hays, an inspired jazz artist who’s performed and recorded with masters such as Joshua Redman, Nicholas Payton, Al Foster, Joe Henderson, and Sonny Rollins.

Grounded in traditional Kurdish folk music, Aynur, 48, sings both centuries-old songs that still circulate in the Turkish countryside and original compositions that often poetically detail the trials and tribulations of Kurdish women. Her arrangements reflect her love of jazz and wide-ranging collaborations with the likes of Kurdish Iranian kamancheh master Kayhan Kalhor, Spanish composer and producer Javier Limón, the great Hamburg-based jazz orchestra NDR Bigband, and Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble, one of her most treasured musical experiences (she appeared in Morgan Neville’s 2015 documentary The Music of Strangers: Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble).

“I normally feel so excited when I have to sing, but with Yo-Yo Ma I was so relaxed,” she said on a recent video call from Amsterdam. “As a musician, of course, he’s incredible, but as a person, he’s an example for all the other musicians. He was so humble.”

Beloved in Turkey and welcome on the world’s most prestigious stages, Aynur has become a lightning rod in her homeland because singing in Kurdish rankles nationalists who have long fought Kurdish cultural autonomy. Since relocating to Amsterdam in 2012, she’s only been back to perform in Turkey a few times, most recently for an aborted tour last year derailed by accusations that she supports terrorism (meaning Kurdish separatist militias).

“We had a big show at an outdoor theater in Istanbul, and they found a Kurdish flag nearby,” she explained, noting that extreme nationalists tweeted about her, calling her a terrorist. "For 18 days, it was a trending topic on social media and even spoken about in parliament. We had to cancel several concerts.”

One of the largest ethnic groups in the world without a country to call their own, Kurds were cut out of the action when the Middle East was divided up after World War I. Subsequent wars have brought tragedies and opportunities. Kurds of northern Iraq attained a measure of self-government in the uneasy aftermath of the U.S. invasion that deposed Saddam Hussein, while Kurds of Syria, the country’s largest minority group, played a central role in the brutally quashed civil war that broke out in 2011, which led to Turkey occupying a northeastern swath of the country.

Kurdish Iranian women have been at the forefront of the movement sparked by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who was reportedly beaten in custody after her arrest for not properly wearing a headscarf. While the political situation in Turkey is volatile, it’s much less dire than in the 1980s and ’90s, when a civil war raged in the eastern Turkish countryside. The Turkish state was so threatened that even speaking or teaching Kurdish put one in legal jeopardy.

Aynur Doğan and her family fled fighting in the eastern province of Tunceli in 1992 and settled in Istanbul, where she immersed herself in music, studying Ottoman long-necked lute — saz (bağlama in Turkish) — and Turkish folk singing. She released her debut album, Seyir, in 2002, but it was her 2004 follow-up, Keçe Kurdan (Kurdish girl), that made her a star. Briefly banned because a court found that one of her songs might encourage women to leave their husbands, the album gained international attention, and her visibility coincided with the easing of the separatist conflict.

She was featured singing Kurdish songs in Yavuz Turgul’s 2004 film Gönül Yarasi (Lovelorn) and included in Fatih Akin’s 2005 documentary Crossing the Bridge: The Sound of Istanbul. One reason she hasn’t performed more often in the United States is that getting her band into the country has become increasingly laborious and expensive. Acquiring the necessary visas is now a prohibitive hurdle that cuts American audiences off from independent artists without deep institutional backing.

“It’s another difficult thing we’re still trying to fix,” Aynur said. “I can’t bring my musicians. It’s so difficult to get an appointment at the American consulate. Only I could get my appointment. Fortunately, Kevin is a great pianist, and Ismail knows this music. We know each other from Turkey.”

She just recorded a new album with a jazz quartet and will be including some of the material in Saturday’s concert. Whatever the arrangement, the starting point of every piece “is always traditional,” she said. “I really like very old songs. I love to listen to them, and I like to give them to the new generation.”

Aside from Aynur’s remarkable voice, the power of her performances stems partly from her 360-degree perspective, encompassing the music’s deep history and its essential role in the future of her people. She relishes presenting these songs to audiences around the world, but soon Aynur plans to turn her attention to passing on everything she’s learned.

“There are a lot of singers in Kurdish music following me,” she said. “When I get to 50, I only want to share all my experience with the new generation.”