At home in Philadelphia. A Black woman sitting on the leather recliner next to her bed. Alone, early afternoon, holding a ten-shot cup of Italian espresso. Up since 5:15 a.m. even on Sunday. Waiting. A lioness in winter. In a working-class neighborhood. In her early 40s, perhaps. To people who know her, Othalie Graham is simultaneously serene and volcanic. And yet maybe too kind, too magnanimous.

It’s an odd thing to say. To herself, she is ever pent-up, afraid that one day she won’t be able to cap all the grief, joy, and uncertainty of the last 25 years. Indeed, there are times when she’s convinced that only her voice — the warmth of it, those gleaming high notes, not unlike Ghena Dimitrova, but even more beautiful — she’s convinced that only her voice will save her. And then only by a rising curtain.

It’s a well-lit room. On the bedside table, a well-worn gratitude journal. The walls are filled with photos of her parents — she Canadian, he Jamaican, hence the luminescence of this woman’s skin. Her voice coach calls it the color of “café au very, very lait.” And then photos of her husband and son, and two autographed photos of Birgit Nilsson. As Turandot in one; Tosca in the other. Somebody gave her those as gifts years ago. Birgit has always been a spirit guide, Graham’s absolute favorite, in all repertoire, not just Wagnerian. Think of her Aidas, her Verdi Requiem. Birgit is also the first person she sees when she steps out of bed in the morning.

And then notice the little picture of the Shroud of Turin. The mother of a colleague gave her that and made her promise always to keep it, and for whatever reason Graham always has. No matter where she’s lived and even if she’s become a disillusioned Catholic. When her father died in 1998, at age 48, of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, quickly and a little unexpectedly, she had only her immigrant fortitude to rely on. Her faith went to hell and never came back. Still, it’s also true that backstage, as the lights dim and the audience quiets, nobody asks for God’s grace more fervently than Othalie Graham.

***

Incidentally, she’s always disliked the name, taken from her father’s mother. People never get it right. It’s embarrassing. “Couldn’t I have a nickname,” she once asked her father. He shook his head and said in his huge voice, which he used to intimidate boyfriends waiting in the vestibule. “People couldn’t say Tchaikovsky; they’ll get over it.”

Right now, she’s just back from the Queen Elizabeth Theater in Vancouver where she sang Santuzza, in Cavalleria rusticana. Now she’s off to a Master Recital Series in Michigan. In a minute the phone will ring. It will be a journalist calling to finish a profile. Naturally, they’ll begin talking about the war. Graham will say how important it is for artists to speak out and vehemently denounce atrocities. Of course. And she has many Ukrainian friends. But on the question of banning Russian singers or deporting them, she will go off the record. The irony is that she’s always wanted to sing in Russia. To come on stage at the Perm or the Mariinsky, or the Bolshoi, of course. What would she give? At the same time, she doesn’t want to pass on rumors, even stories she’s convinced are true, because you never know the whole story, you never know people’s true loyalties, especially now. Especially against the backdrop of the little madman dancing with his shadow. A casual remark can disconnect a career, undo a family, poison a friendship. Never forget the unintended consequence.

By the same token, it’s not in her nature to ostracize, to “cancel.” Which is why she’s careful about posting her political affiliations on social media — and the reason she’s blocked certain people from commenting on her posts. When George Floyd was murdered, someone wrote, “We shouldn’t see color. We should just all get along.” Graham’s first thought was, “How naive can you be? If you say you don’t see color, then you don’t see me and you don’t see the atrocities that are happening.” She blocked that person.

These last two years of the pandemic have been a singer’s particular nightmare, between the threat to lungs and the dreaded mask. At the outset, one of Graham’s engagements canceled, and she thought “well that’s probably the worst of it,” but then another and another canceled. Twenty-five or 30 performances altogether. Beethoven Ninths, Turandots. A Verdi Requiem. It was crushing. She knows five or six singers who have become destitute as a result. Another 20 were forced out of New York.

Think of it. You’re making say, toward the lower end, $5,000 or $6,000 a performance, and many make less than that, but you can only scratch together three performances a year. Your rent or mortgage is $1,500 to $2,000 a month. Not to mention agency fees, taxes, and voice lessons. And all the rest. Unless you’re a two-income family you can hardly do it. Or unless you’re in the top one or two percent of opera singers. So as a result, many of Graham’s friends went into real estate or nursing or business school. They moved in with parents or friends. Graham has been lucky, and careful. Her husband, her salt-of-the-earth husband, is a financial advisor. And then also she’s gotten the work. But all the while, she goes to grocers looking for the manager’s special or else meat with a sell-by date of that day.

And then on top of the virus, just before it took off in 2020, while Graham was playing Lady Macbeth, her mother found a lump in her breast. And so begins a whole other story about Graham the caregiver, ricocheting back and forth between Ontario and Philadelphia, two months with her mother, one month at home, first for the biopsy, then the surgery, the radiation, the chemotherapy. This went on for a year and a half. Suffice to say her mother is doing well. The two talk, sometimes several times a day.

***

Graham’s first coach was the renowned Lois McDonall, who sang Freya on Sir Reginald Goodall’s famed English National Opera Ring cycle recordings. She’s the one who first got Graham on track. She was also the one who first said to her, “Life happens while you’re singing.” Parents die. Children grow up. Even good friends fall away.

After Lois, Graham spent time with Bill Schuman who taught the craft to such singers as Michael Fabiano, Steven Costello, and James Valenti. Schuman is, by reputation, the number-one voice teacher at the Academy of Vocal Arts (AVA) in Philadelphia. And then came Jeffrey Miller, who has been Graham’s coach for last 16 years. He’s 69 and lives outside Philadelphia, 50 minutes from Graham who he sees two or three times a week. He was the music director of Opera Delaware between 2007 and 2017, but in recent years has withdrawn from the scene except as a coach and church musician.

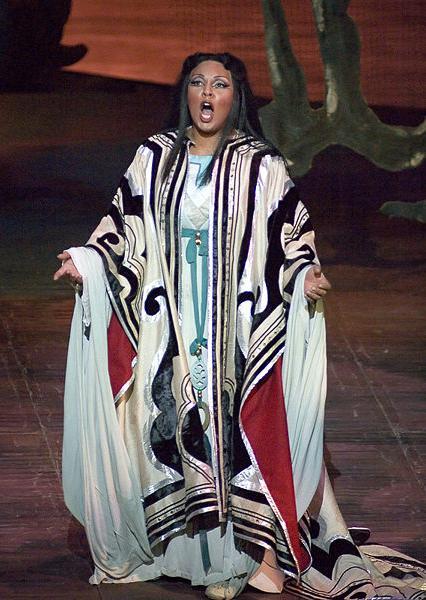

He met Graham when she came to audition at Opera Delaware for the role of Turandot. Which has become her signature. Miller remembers it vividly. “David Lofton, one of the coaches at AVA, brought her. They were close friends at the time. So he brought her down. We didn’t know anything about her. She looked gorgeous. I remember she wore a white dress and just looked so sunny. She’s a gorgeous, gorgeous woman. And she sang the living daylights out of “In questa reggia.” I mean literally. I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, is this Eva Turner before me?’ It was unbelievable. Big, big, cavernous high notes and dead center pitch. And so we hired her.”

***

Backstage, at the end of an evening performance, when colleagues go off for a drink, Graham ducks out to the hotel and calls her son, Koron, to help him with his homework. She has him read all his assignments out loud, and never misses a day, not in all these years, whether at home or on the road. And it’s made a great difference. When she first met him — he’s from her husband’s previous relationship — he was close to being non-verbal but now his language proficiency has greatly improved.

He’s now 20, six-foot three and rows every morning. “He’s ridiculously strong and muscular,” says Graham and you can hear the pride in her voice. “Because of his disability, he seems a lot younger than he is. He’s just very sweet, very loving, only wants to be with the two of us. During the pandemic, people were always saying, ‘Oh, my kids are in the house with me. I can’t get away.’ But we’re always doing things together. And it’s very comforting, and he’s very protective of me, physically protective. He grabs my hand when we cross the street, stands in front of me, all the things that his dad taught him to do. ‘In case something happens, you’ve got to take care of your mom.’ I didn’t think that I would have children and it’s the greatest gift I could ever have been given. For my mother too, because he’s so happy to have a nana and they talk every day.”

***

“No one has said that to my face,” Graham was saying in another conversation. “No one says, ‘we don’t want a Black singer.’ But of course, there are a lot of artistic administrators and directors that have an inherent bias that they would never recognize as systemic racism. I’m also thinking of some singers, who because of their celebrity, can get away with things that Black singers could never get away with. Like just bad singing. Like just bad behavior. Consistently late for rehearsals, missing rehearsal altogether, being rude to staff, all that stuff that’s considered “diva behavior,” which to me means being even more gracious to the people around you, because you’re seen as a role model, and you need to act as such.

“It reminds you of the old adage that our parents taught us, ‘you have to be twice as good to get half as far.’ Well, that hasn’t changed. We’ll sit in an audience, absolutely dumbfounded at sounds coming out of a singer. And please, we’ve all not sung well in our careers, myself included. But it seems like there are more artistic directors and administrators that look the other way, depending on how famous a singer is. If they are in the top one or two percent, then they certainly get away with more.

“By the same token, I find critics come after us much more now. There was a time when you could go to the Metropolitan Opera, and Reri Grist was singing. Jessye Norman was singing. Kathleen Battle was singing. There were so many. Martina Arroyo was singing, Leontyne Price was singing, color wasn’t such an issue. It didn’t seem as unusual then. Now, you’ll have an opera house hire two Black singers — and consistently hire the same two Black singers — and then applaud themselves for appearing not racist.”

There are exceptions. “For example, Nashville opera [Artistic Director] John Hoomes is a perfect example of that. I had done Turandot with him at Arizona Opera, and so many different opera companies. And he said to me one day, “I see you, vocally hear you, but I also see you as Minnie in The Girl of the Golden West.” And of course, that’s always a blonde, thin woman. And he said, “You’re so beautiful. Your voice is perfect for this role.” And we’ve done it together twice since then.”

Graham points out that there is now another kind of racism in play, in which singers of color are only cast in roles originally designated as their ethnicity. The idea of color-blind casting, on the other hand, is to expand the roles BIPOC singers can be considered for to include the entire repertory. “When you say that Butterfly can only be an Asian soprano, then yes. [But also] hire a Chinese soprano for the Countess. Hire a Chinese soprano for Electra. But saying that Butterfly can only be [cast with a] Japanese [singer] because [the character] is Japanese is not right. What role does that leave for me? Porgy and Bess? No thank you. Dallas Opera [cast] Latonia Moore, over 40, soprano, curvy, short, Black soprano, thank goodness, and she’s one of the best Butterflies. So again, there are a few companies that are doing it, but certainly not enough.”

***

Graham has never sung at the Met, which is not so unusual, even for such a consummate performer, but certainly a disappointment. One story that might explain it is that she ran afoul of a particular voice coach who was very powerful, didn’t like her voice, and said some unkind things. Graham has no comment on or off the record. “Painful” is all she’ll say. “The things he said just weren’t true,” says Miller.

“They were so subjective. How do you argue subjective? ‘Well, that’s a warm sound.’ ‘Well no, I think that’s a cold sound.’ ‘No, no, that’s a harsh sound.’ I think it was all because of the ‘Met machine.’ Graham doesn’t fit into that. I mean, she’s not one of these people willing to let anybody monkey around with her voice. And when you go to the Met they immediately say, ‘well, you’ve got to go along. You’ve got to do it our way.’ The fact is you have to have a big sponsor. Graham hasn’t had one and her response — and not just to the Met but to many A houses, Vancouver being an exception, she’s always welcome there — her response has always been, ‘I’ll let my voice respond.’ The problem is that once you slip into the second string it’s very hard to get out.”

“What could she still achieve?” adds Miller. “I’m hoping, that for the last 15 years of her career, she’ll start breaking into the Wagnerian roles. I would love to hear her sing Elsa [in Lohengrin.] A lot of people think Elsa’s a snore. It’s really not. But you know how she could make her name in the opera world? All she needs is one Siegfried Brunnhilde. And let me tell you, the phones would be ringing off the hook the next day.”

***

Among the photographs and mementos hanging on Graham’s bedroom wall is her father’s baseball cap, which he started wearing during chemotherapy. Next to that the pen that nurses used to document all of his vitals. In her bedroom closet are the clothes he wore the last time he went to the hospital, which include a pair of jeans, a T-shirt, and a long plaid shirt. He also wore his leather workman’s belt, which hangs on the wall.

It’s impossible to measure the effect of her father’s death on Graham. It became not just a terrible absence but something more aggressive, more sinister, the tearing away of her identity. Sometimes, it was as though she were being haunted. She tells this story. “After a performance, I had just finished singing and we were all standing around together talking about where we’re going to dinner and a man who was in the chorus started to walk toward me as I was heading to my dressing room. He was wearing a Nehru jacket shirt kind of thing, in that camouflage green color that my father always wore. He was big, muscular, dark-skinned, bald head. So similar and yet just like a normal guy in the chorus. I had a visceral reaction just seeing him and immediately raced to my dressing room. Had to stuff down what I knew was starting to bubble up, which was that feeling that I’m constantly stuffing down to survive.”

And then there’s the night her father died. “He died in the hospital, and I stayed with him for several hours and then went back home and went to bed. Of course, knowing I was probably never going to sleep again. And then suddenly I heard him calling me. It was so loud. I got up and went down to the garage. He did a lot of trades stuff, electrical, plumbing. He was always building things in the garage. By the way, he was a kind of hero in Brampton. At his funeral all the unions came. It was a huge event. But that night I heard him calling and I went downstairs, opened the door. And it wasn’t like in a dream. He was standing there with his back to me. And then he turned around and said, “promise me that you’ll take care of your mother.” And I thought but what about me? And then he said, his voice was always so authoritative, ‘Take care of you mother and I’ll take care of you.’ And that’s just what’s happened.”

***

Toward the end of the last interview, the journalist pressed Graham for some key to understanding how she sees herself — literally. What do you see in the mirror? he asked. “I absolutely love my face,” she replied instantly and with no vanity. “Not because I think I’m special looking, but because I look so much like both of my parents. It’s a perfect combination of both of them. So every time I see pictures of myself I always look exactly like them. And when I look in the mirror, I always see my father’s face, always.”