We were in Big Sur a few weeks ago, to help bury the ashes of the great cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond, at his condor’s nest near Pfeiffer Pt. The "master of shadow" died at 85 on January 1, leaving a legacy that includes Deliverance, The Deer Hunter, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, for which he won an Oscar, and that notorious masterpiece directed by Michael Cimino, Heaven’s Gate.

The mourners were Hungarian filmmakers and local Big Sur types: musicians, poets, painters, pot growers, surfers, craftsmen of every kind, and an older, lady Gatsby dressed in vintage psychedelic chic. It may be fair to say that Big Sur is one of the few wealthy places in America where lords and serfs commune together and where everyone seems to be an artist, including the “plumbers,” as Henry Miller put it.

At lunch following the memorial service, the tittletattle was about whether short-term housing rentals should be regulated, and how Big Sur is being overrun by tourists, a refrain that goes back to Henry Miller’s time when anyone who discovered the place wanted to be the “last invader.” How it’s harder to get into Deetjen’s, the landmark favorite for breakfast. How the scraggly, pot-holed country lane from Hwy 1 to Pfeiffer Beach, is clogged with people and cars, even in winter. How there’s growing opposition to any more growth: period. How incidents of road rage are increasing, and how treasured campsites in the backcountry have become wrecked with trash, which was also a complaint in Miller’s time.

And there was one other topic that came up apropos of growth in Big Sur: Whatever happened to plans for the Philip Glass Center for the Arts, Science, and the Environment?

Dreams Are Made of This

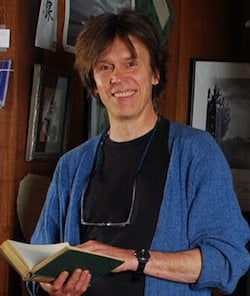

One of those at the memorial service was Magnus Toren, a tall, boyish Swede, glasses riding atop his forehead. He’s the long-time director of the Henry Miller Library, and landed in Big Sur in 1984, Drake like, after having sailed around and about the world for seven years. Eventually, and inevitably, he became bewitched by the curvy landscape, which has always reminded him of pregnant women.

“It’s a paradox,” Toren told us, talking about growth in Big Sur. “We live off the generosity of visitors, yet there’s no question that Big Sur is being overused and the increasing number of people coming here is starting to impinge on the quality of the experience.” Magnus predicts that within a year or two traffic gridlock on Route 1 will tip the balance between trendy and quaint, and Big Sur will suffer for its charm in earnest.

Magnus has broadened the library’s appeal as a local literary center that hosts book readings and film screenings, and has been a venue for bands such as Flaming Lips, the Fleet Foxes, and Red Hot Chili Peppers. He would like to invite classical music ensembles but has less cash than barter, albeit first-class dining and hotel accommodations. In recent years, the library has also become home to the annual, week-long Philip Glass Days and Nights Festival. The sixth annual festival is scheduled for late September, after the Monterey Jazz festival.

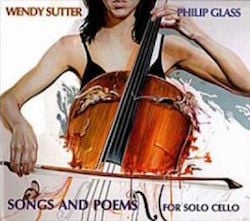

The festival grew out of a benefit concert in the late summer of 2008. Magnus will never forget the night. The outdoor performance space at the library is limited to an audience of 300. But that night the space felt the size of Chartres. Under mile-high redwoods, Toren set out some old Persian rugs, brought in a Baldwin grand piano, lit the spot to capture the ethereals, and on a fogless night presented Philip Glass playing his then newest work, Songs and Poems for Solo Cello.

The soloist was Wendy Sutter, the tall, slender, long-fingered cellist once noted for her “soaring loveliness” by the San Francisco Chronicle. Just then she was in the midst of a five-year romance with Glass and was bewitched by his work, by its “structure and counterpoints.” His music reminded her of Schubert; other times he seemed to her like “a minimalistic Bruckner.” But above all, she said at the time, she was struck by the “huge emotional pool of his music, which tugs at your heart and your being.”

Sutter can appear distant onstage, but not that night. She was clearly in love, or so it seemed to Magnus, who is as worldly a man as you’ll ever meet. For him, the performance was an erotic experience. How else to see it? The way she opened her legs to embrace that most sensual instrument, and the way she moved with it, not against it, and then, of course, the intensity of her facial expressions. Not to mention the music, itself. It all seemed more than sensual.

Referring to that night, Magnus said, “I think the experience of playing onstage in that redwood grove, beyond his relationship with Wendy, I think it rekindled some long-held love affair Philip had with the Big Sur Coast, as well as one he’d had with Henry Miller. Philip once drove his motorcycle up the coast looking for Henry; that was in the late 1950s, but he didn’t find him. But the welcome he received that night, and during that period of time he was here, the dinners we had, the wonderful long walks, and the quiet time in a small cabin on the hillside where he stayed. All of it added to the conspiracy that led to the Festival and the pursuit of a Glass Center!”

The Glass Cultural Center

Glass’s concept of a Center is to “gather the world’s leaders in the fields of art, science, and the environment for a broad array of interdisciplinary activities including performances, seminars, and education programs that inspire and motivate the public to become engaged with matters vital to the future of the natural environment and the quality of human existence.”

The idea for the center was concretized in 2011. A spot was chosen, an architect found, and renderings made. In 2012, a proposal was offered to the U.S. Forest Service, which owns the land and had long been interested in just such a project.

The plan was to build on a piece of public land known as the Brazil Ranch, just south of the Bixby Bridge, which stands at the northern perimeter of Big Sur. The property is 1,226 acres and was developed by Allen Funt, the originator of Candid Camera. He died in 1999 and long time caretakers have continued to manage the property, which was bought by The Trust for Public Lands in 2002, for $26 million.

The Glass Center would occupy a 160-acre parcel, which includes grazing land, two barns, a ranch house, two ‘Indian’ houses, and some sheds. The proposal was to transform the 5,300-square-foot main barn into a performance hall with 140 seats, along with three practice rooms. The smaller barn, a hay barn, was be made into a dance studio and stage. The Indian houses were to be made into guest houses.

Between the two barns, the plan was to build an 8,600-square-foot performance hall, which would seat an audience of 400 to 500. The plan also called for 21 “tent cabins,” each 144 square feet, for musicians, artists, and scientists in residence. Under the plan, the Center could house up to around 40 people for seminars. There was a substantial area for parking, but more in keeping with Big Sur these days and a plan used during the festivals, the idea was to bring in patrons by minibuses from Carmel.

“‘We love the idea,’ the Forest Service told us,” said Jim Woodard, general manager at the Philip Glass Center. “They were very encouraging. But then nothing happened and finally they said that the sequester had ruined their budget and they just didn’t have the money to rehire people to process a huge backlog of permits, much less new ones. In January 2015, after three years, they returned the application and said simply, ‘we can’t deal with this.’”

According to Woodard, the district manager for the Forest Service summed up the problem: “We fight fires and lawsuits and that’s all we have time for.”

The option for the Forestry Service is either to sell the property back to private interests or else decommission the property, which would mean removing all structures along with the access road, and turning the property back to wilderness.

“Whatever they do,” said Woodard, “it will take years.”

The architect for the Glass Center is Mary Ann Schicketanz. Asked about the prospects for the project she replied, “I think that right now it all depends on how powerful an organization Philip can build. If you don’t have the right people in place, it just won’t happen. You need to be able to raise the money to have the right consultants, the right lobbyists, and then somebody who can really administer it all efficiently. You also need a staff person in the Forest Service dedicated to processing the application.

“It’s important to remember that ironically this plan is exactly the kind of project the Forest Service — and the Coastal Commission — have been looking for, and the only real alternative is to let the property fall into disrepair and decommission it, which would be hugely expensive.”

Virtual Realities

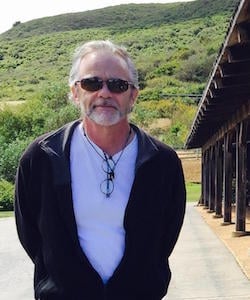

We reached Philip Glass to ask about the project. He was at home in New York — he comes to Big Sur a couple of weeks every year, for the festival. We found him caught up in the opening of the revival of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, for which he wrote the score.

“We’re kind of waiting it out and I haven’t got another place in mind. On the other hand, we’re doing very well, we have very good relations with the library. I’m still basing the work out of California and I plan to continue doing that, so we’ll see what happens. I’m willing to wait but Mother Nature is not willing to let me wait forever.”

In sum, he said, “We’re kind of a homeless institution, but it has a bright side to it because we can get out and play in other places.”

‘Other places’ include the Garrison Institute in Garrison, New York, which may become a satellite facility for the culture center; City Winery in Greenwich Village; and an old and very popular arts center in Amsterdam known as the “Milky Way.” In Northern California, other places include Asilomar and Hidden Valley Music Seminars in Carmel Valley, a couple of venues in Monterey, as well as the Big Sur Library.

“What I’d like to do,” says Glass, “is to make the place a center for a limited number of people so we could get involved in film and radio broadcasting. There are places like Montreal, Paris, and Vancouver and Berlin; we’re talking about starting a network between all these places. I can’t go into detail but I am talking actively with people who have similar ideas and are interested in a new kind of network.

“I’ll give you an example, I travel a lot and I wake up in the middle of the night in my hotel someplace and what am I going to look at? CNN or the BBC? There’s nothing to look at. And so what if there were a cultural channel — I mean a real one — not one financed by the government, which would immediately handicap them. This would be done by people who are passionately involved in the arts. What if I could turn on a channel to find out what’s going on with modern dance in the city I’m in right now or what theater in South Africa looks like these days. We have the capability to do this, the means to do this is now.”

Glass acknowledges that there are organizational problems with such a project, “but they can be solved and, of course, I’m not the only who’s thought of it …. And we’re not talking about the international endowment for the arts and crafts or anything like that …. These government-funded things have their own problems and I have stayed away from institutions of that kind anyway, and they’ve stayed away from me. And that’s okay; it hasn’t stopped me from working. I can still do the work I want without having to explain it to anybody ….”

And how hard is it to find the money for this?

“It’s hard for a small theater company to do just one project. I’ve talked to people and they want to talk about 'sustainability' and I say, ‘wait a second, do you think the Metropolitan Opera is sustainable? They have to raise hundreds of millions of dollars a year.’ There’s no such thing as sustainable art programs. And a lot of people don’t understand that.”

Standing on the Shoulders of Others

In his memoir, and in interviews in recent years, Glass talks about “Music as Place,” and recently has refined that to the idea that music is innate in all things. He also talks about the nature of trust and collaboration, but, above all, he talks increasingly about continuity and lineage, and the idea that continuums afford people the opportunity to find identity in large ideas.

Hence the real emphasis of his center is on cultural lineage.

“We are always standing on the shoulders of other people. I’ll tell you a very funny thing. In my own case, my teacher was Nadia Boulanger whose teacher was Gabriel Fauré. My own personal legacy goes back to the 19th Century and this is the 21st Century!”

As an aside, if you trace this lineage back further, you find that Fauré’s great teacher was Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921) who was taught by Camille-Marie Stamaty (1811-1870), one of the most distinguished piano teachers in 19th-century Paris. He, in turn, was the star pupil of Friedrich Kalkbrenner (1785-1849), at his peak, in the 1820s, the foremost pianist in Europe and a prolific composer. And from there the strand winds back still further, ever more faintly, to Louis Marchand (1669-1732), one of the great organists of his day.

The point, said Glass, is that there is both a horizontal and a vertical quality to his cultural center. On the one hand, it represents the value of collaboration, with scientists, environmentalists, and activists of every kind, social and political. On the other hand, the center is an expression of the nature of roots, and of past, present, and future.

As for Big Sur, Glass is on the local continuum, and might be thought of as the Henry Miller of the day. “Well, maybe so,” he said, “but the generation before me was really the Allen Ginsberg generation.” He added, “I want to go back and read Miller now. One of the reasons I went to live in Paris when I was in my late 20s was because of his books. I was interested in the bohemian artist’s life that was going on there in the 1950s, and I was not disappointed.”

It was in Paris that Glass found Nadia Boulanger.

Endings in E Major

Of course, it’s the illusion of very beautiful places that if you can only live there all else will be bearable and happiness made impregnable. The day before he died, we wheeled Vilmos Zsigmond, the great cinematographer, to a spot where he could enjoy his favorite view of the coastline, and once more enjoy the opulence of light and shadow, which first drew him to the place so many years ago. But now the splendor seemed to have dulled. Too painful, perhaps; more like a postcard than reality, and too distracting from the mortality he was focused on.

“I’m cold”, he said after just a few minutes, and without another word we pushed him back to his studio.

The great promise of Big Sur, with all its beauty and hopefulness, the maddening love it inspires, seems thin at such moments. In Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch, Miller acknowledged that this particular paradise is not for everyone, and as he found out for himself, it can be hell on personal relationships.

In 2013, five years after Philip and Wendy played at the Henry Miller library, and the spell from that night had unwoven, a cooler Sutter told a reporter in Tucson, “I would say the relationship honestly was based more on work than romance. It was kind of an old-fashioned, Victorian relationship. He loved to write music for me and I loved to interpret it and play it.”

She told the same reporter, referring to Songs and Poems for Cello, that she had had serious doubts about recording the piece: “It was either going to come out covered in gold or covered in shit. This is so unlike anything that he’s ever written before and I’m playing it with all this bravado and freedom. I wanted to withdraw the recording, I really did. I was really scared that I would just be trashed by the critics.”

Glass persuaded her not to withdraw and the recording went on to attract critical acclaim and has sold more than 85,000 downloads. Which may tell you more about Philip Glass than Wendy Sutter: When Glass believes in something, he doesn’t give up. As he wrote in Words Without Music, “I have a wonderful gene — the I-don’t-care-what-you-think gene.”

But now, eight years later, did he remember that wondrous night when so much of the future seemed in hand? Yes, he remembered it exactly and just as Magnus had described. “That’s very true. Playing in that beautiful redwood forest.”

And Wendy Sutter?

“I have a lot of collaborators,” he replied cryptically. “I always have. That was an important one. But there are other ones as well”

There was a pause.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I have to go back to work now.” And with that he hung up.