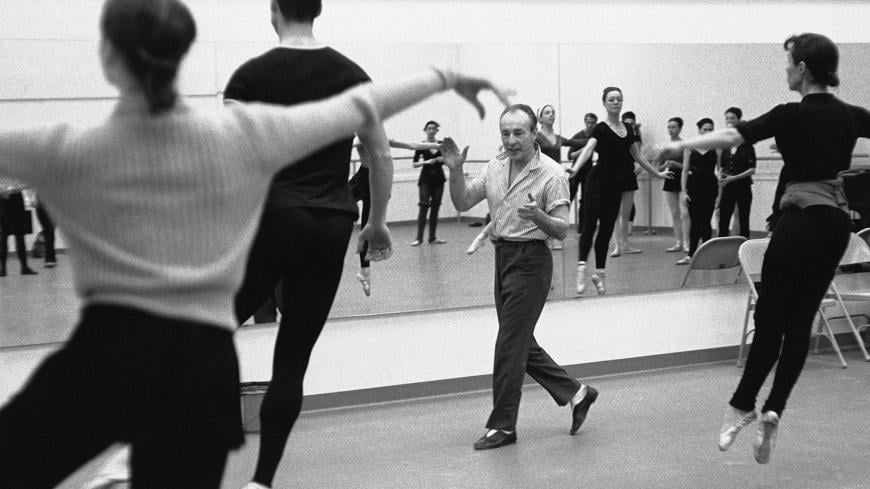

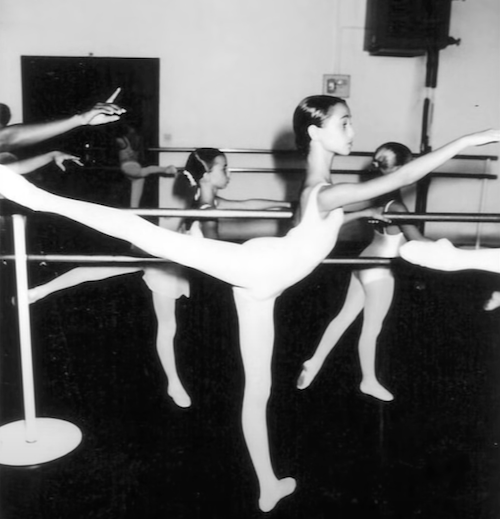

It’s no secret that dance is an exceedingly competitive, high-stress, and physically demanding profession, with the world of classical ballet known for having placed great value on women’s looks, a kind of body fascism, if you will. Indeed, when George Balanchine co-founded New York City Ballet in 1948 with Lincoln Kirstein, he soon created what would ultimately become the coveted look of ballerinas in the 20th century: long limbs, a notable absence of breasts and hips, an über-thin frame that accentuated the collarbone, and an elegant, swan-like neck.

Balanchine, some would also say, created a culture of eating disorders. In her 1986 memoir, Dancing on My Grave, former City Ballet member Gelsey Kirkland wrote that the choreographer would routinely make comments such as “eat nothing” and “must see the bones.”

But that was then, and while that culture still exists to some degree, ballet — and, in particular, women — have come a long way. Also more prevalent now is the notion of getting pregnant, having a child, and being able to return to dance. Mathilde Froustey, principal ballerina of San Francisco Ballet, has successfully navigated both terrains.

Having had a son last August, Froustey, who was born in 1985 in Bordeaux, France, was back onstage again in December. Reached by phone in San Francisco, the dancer, speaking in heavily accented French, admitted that it was “really hard. Not only I went through my pregnancy, but it was also COVID. I stopped for a year and two months. I’m still trying to be back to my level, but I’m not there yet.

“I’m my own worst critic,” she added, “and it was challenging, but it was also amazing.

“I’m still breast feeding my little guy, and it’s hard to be onstage, rushing back home to feed him, going back to rehearsal, but it’s been wonderful.”

Froustey’s terpsichorean journey has also been unique: Beginning at Paris Opera Ballet School in 1999, she joined the iconic Paris Opera Ballet (POB) in 2002 and was promoted to Sujet (soloist) in 2005. And though she appeared in leading roles, notably as Kitri in Don Quixote, she never ascended to Première Danseuse. Frustrated at being overlooked, Froustey reached out to San Francisco Ballet’s Helgi Tomasson, who leaves SFB at the end of this season, after having joined the organization in 1985 as artistic director and principal choreographer.

He’d seen Froustey dance in 2006 and liked what he saw: Fast forward to 2013, when the ballerina sent Tomasson an email along with several videos and — voilà — he offered her a contract as a principal dancer. Deciding to take a leave of absence from POB for a year to test the waters in the City by the Bay, Froustey has since become a beloved company member.

She recalls that, as part of her decision, she would have had to choose between living and working in her native France and a career in San Francisco: “It was difficult because with Paris Opera Ballet comes free education, and my family is also in France — all these things. In San Francisco, I had the roles, the title, but in Paris I was still a soloist [who] didn’t have the title, and maybe I never would. It was a gamble, but the peace of mind I had in San Francisco was really precious.”

What was not so precious, though, were her struggles with an eating disorder, as well as her attempts to get pregnant. Initially trying to conceive in 2017, it proved difficult because she worked constantly but admitted to eating very little; consequently, she stopped having her period.

In 2019, Froustey married Mourad Lahlou, but her battles continued. “To be honest,” she recalled, “we’d been trying for a few years to get pregnant, but because ballerinas are really, really slim, it’s not easy for some people to actually have babies. And going onstage every night is not easy. If you have a bad night, if you’re tired, you still go onstage.”

To that end, Froustey began in vitro fertilization, after which, she explained, “COVID hit. My husband is a chef, and with the restaurant closed and the ballet closed, money-wise, it was going to be difficult.”

Nature has a funny way of working, though, and Froustey managed to get pregnant without IVF. “But I had two miscarriages. It was devastating, and it’s hard for me to talk about it. And when I got pregnant again, it was three days before I was to go back to the ballet after the miscarriage, and I told Helgi I’m pregnant again.

“He was making a new ballet,” she continued, “and he said, ‘I don’t want to see you at the ballet for the next three months. You stay home, you rest [but] I don’t want to see you.’ It was because of that, that this baby was fine and I didn’t lose the ballet. Helgi was really nice to me, and I will be thankful all my life for him.”

As for Froustey’s eating disorder, a topic that was considered hush-hush for years, the dancer was open and honest about the disease that has claimed the lives of several ballerinas, including that of 22-year-old Boston Ballet dancer Heidi Guenther in 1997.

“Our art is so, so hard on the body,” said Froustey. “In my generation, we didn’t have a lot of help, but in this generation, it’s better, and principal dancers must talk about it. We work with our bodies, sometimes things happen and you go too far on a diet. I had an eating disorder before I got pregnant and was scared that it would come back.

“During COVID, I went to treatment for six weeks, and that was in the summer of 2020,” recalled Froustey. “It’s better now and it’s weird, because the last few years, things got better because of COVID. You don’t need to have such an extreme body; you need to be healthy and happy and you can be a good mover. The movement is important, but not the way you look.”

The pandemic also allowed companies the time to reconsider the issue of weight, with The New York Times’ Gia Kourlas reporting in March of last year on what a ballet body — and a healthy body — look like. Her story noted that City Ballet’s Artistic Director Jonathan Stafford and Associate Artistic Director Wendy Whelan (both having been principal dancers with the company) instituted a new rule that, “No staff member is allowed to talk to a dancer about a body-issue concern without protocols to ensure sensitivity and confidentiality.”

Still, the achingly thin but racehorse-strong dancers that populated Balanchine’s ballets have also inhabited the Broadway stage. Laurie Kanyok performed in numerous shows on the Great White Way, including playing the lead in Twyla Tharp’s Movin’ Out, set to the music of Billy Joel, as well as having danced in movies and on television. In 2018, she created New York City-based Kanyok Arts Initiative, a teaching and mentoring program for 14–19-year-olds. She explained that the issue of food has been a constant in her life.

“It never went too far with me, but it’s something that you always have. I have this joke from when I was doing Movin’ Out, and the musicians in the band were in awe of us and would ask, ‘How do you look like that?’ I would just say, ‘Put the fucking fork down.’ It’s really that simple, but that took me years to get to that place personally. We don’t need, as humans, American-sized portions of food that they sell us.

“It’s a daily struggle,” Kanyok confessed, “but I eat properly and the average amount of food to survive. Do I look at 50 the way I want to look?” she asked rhetorically. “Of course I would prefer to have my 30-year-old body,” she said, adding that, “every dancer has a twinge of an eating disorder — whether it was active or inactive.”

Kanyok also pointed out that her generation faced a tougher climate. “The legends of dance I worked for would tell me I was out of shape. [Jerome] Robbins and others, they all had expectations of what a dancer should look like. And they had no qualms about expressing it verbally — or nonverbally — with an eyeroll, for example.”

And while Kanyok never had the need to go to a clinic for her disordered eating, she noted the issue is also “an emotional thing. It comes down to a feeling. I was in therapy when I addressed my emotional woes, and because it didn’t feel good when your esophagus is raw from throwing up and your stomach is cramping from all the laxatives.”

Kanyok, unlike some in the dance world today, thinks that the reality is “still bad. When I see these kids come into the studio with Starbucks and Frappuccinos, I try to impose my harsh educator self on them. I say, ‘What’s in there that’s good for your bodies? It tastes good, but what’s going to sustain you [in class or rehearsal] from 10 to 6?’ And the other thing is that most people don’t cook. Eating out is unhealthy, ordering food in is unhealthy. What’s healthy is what you can control in your own kitchen.”

Someone decidedly in control of both her kitchen and career is Josie Walsh. The founder, artistic director, and choreographer of BalletRED (upcoming performances include The Secret Garden, May 14–15), Walsh is also artistic director of ballet at the Industry Dance Academy. In addition, she helms the Joffrey Ballet School’s West Coast satellite programs in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and in November the artist will be presenting a season of installations and immersive works at The Ruby, a warehouse she’s renting in Pasadena.

“I do feel it’s a better landscape than when I was growing up,” recalled Walsh, who also danced professionally with the Joffrey Ballet and Switzerland’s Zürich Ballet. “There was no real wisdom about healthy diets back then, at all. You would eat fat-free frozen yogurt and a muffin, which was all gluten and sugar, so it’s working the opposite. I was popping diet pills for my whole career.”

But in 2007, Walsh came to an “aha” moment when she became pregnant. “This was the first time I thought that I needed to eat to nourish my body and not worry about how I look. For me, being pregnant was the most helpful in my healing. My eating disorder had to do with external forces making me want to look like I was 12 years old and [the idea that] you’ll be fired if you don’t look a certain way.

“Being pregnant made me see that food’s not the enemy,” added Walsh. “I had to relearn and develop a better relationship with food. It was much easier, because it was for someone else other than yourself.”

For Froustey, who once said she needed to be “happy when I dance,” her eating disorder was the one thing she could control. “It is like little drops of poison in your head,” she pointed out. “When that happens, you believe you’re happy because you’re controlling what you’re eating. The level of control when you have it, you think that makes you happy, but actually you are in jail.

“It’s not that it’s about being happy or not,” added Froustey, “but it’s more that when you’re feeling better, you feel free. You can eat healthy. You don’t need to exercise twice a day; you don’t need to fight.”

With ballet the elite art form that it is, certain physical qualities are, of course, necessary, but is it the critic’s job to judge the body or the performance? The Guardian’s Judith Mackrell once wrote, “To some extent dance critics are all body fascists.”

That may very well be, with Froustey weighing in on this. “Most of the time, they review the performance — they wouldn’t review the body, because you don’t need the review to have an eating disorder, you develop it inside yourself. Things are changing, and I do think it’s important to talk about, and it’s okay to have a problem. We’re not machines, we’re artists. We are showing our bodies in front of 3,000 people every night. It’s okay to have a little crack, which was not the case 10 years ago.”

If it’s true that today’s Gestapo-like weight policies and bony-physique dictums are, for the most part, being replaced by education and wellness and nutrition programs, one can’t help but wonder: If Balanchine, who died in 1983, were alive today, what would he say?

The forthright Froustey had an immediate response. “I don’t see the point of asking what he would say. It’s in the past; it was not really healthy the way they were treating their bodies. Balanchine created amazing ballets, but he’s not a director anymore.

“I danced many of his ballets,” she added. “He’s one of best choreographers in the world, and it’s such a great pleasure to dance his ballets. It’s also a great challenge, for sure. I love dancing his ballets, but I don’t want to know what he would say about body types. I really don’t care [because] if I don’t eat healthy, my little guy’s not going to grow. You have a human life who depends on what you eat.”