Imagine you’re a world-famous pianist like Leon Fleisher and you’re about to play the first-movement cadenza from Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto, a passage you’ve played hundreds of times. Suddenly and inexplicably, your fingers aren’t responding properly to the messages sent by the brain and the endless hours spent building muscle memory. That could signal the onset of a career-ending disease called focal dystonia.

Eckart Altenmüller and Hans-Christian Jabusch’s article “Focal Dystonia in Musicians: Phenomenology, Pathophysiology, and Triggering Factors” (published in 2010 in the European Journal of Neurology) describes it this way:

Focal dystonia in musicians, also known as musician’s cramp or musician’s dystonia, is a task-specific movement disorder which presents itself as muscular incoordination or loss of voluntary motor control of extensively trained movements whilst a musician is playing the instrument. For those who are affected, focal dystonia is highly disabling and in many cases the disorder terminates musical careers.

Musician’s dystonia may be classified according to the task specifically involved. For example, embouchure dystonia may affect coordination of lips, tongue, facial and cervical muscles, and breathing in brass and wind players, whereas pianist’s cramp and violinist’s cramp may affect the control of finger, hand, or isolated arm movements. According to recent estimates, 1 percent of all professional musicians are affected.”

Dr. Xenos Mason, who’s also an accomplished French horn player, works at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine. He is the founder of the multidisciplinary Musician’s Neurology Clinic within the Neurology Department, which, in collaboration with the Musician’s Health and Wellness Committee at USC Thornton School of Music, provides resources and treatments for the numerous injuries that plague musicians and dancers and includes specialized research in finding answers to focal dystonia.

“I wouldn’t say performing arts medicine is a recognized specialty, but it is definitely an area of interest that first arose in the 1980s,” states Mason. “Today there are multidisciplinary performing arts medicine programs at institutions around the country. And since I am a French horn player, musicians are people I enjoy interacting with. It’s a population I understand, especially regarding issues of fine motor control and how important subtle changes in function are.”

Mason can also cite a personal connection with focal dystonia:

I had a teacher, a horn player, and she stopped playing because of an embouchure issue. So, I was aware of this issue from a comparatively young age. Our clinic [which opened in September] was created to serve the music community of Los Angeles and Southern California, including passionate amateurs, students, and professionals. Our mission is to preserve and restore the ability to make music. We provide evaluation of suspected neurologic conditions and subspecialty diagnostics and treatment, with a particular focus on musician’s dystonia and nerve injury/entrapment. The clinic provides multidisciplinary care with integrated evaluation and treatment by neurologic-specialist physical and occupational therapists. We offer EMG-targeted intramuscular Botox injections and referral to partners in orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery for any necessary procedural treatments. We also interface with musician’s wellness programming at the USC Thornton School of Music. We offer these resources to patients with the goal of providing comprehensive care and restoring musical function.”

Is There a Doctor in the House?

“I am not a doctor,” William Kanengiser says categorically. “I am a classical guitarist [and founding member of the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet]. I’m on the faculty of the USC Thornton School of Music, but I don’t even have a doctorate in music,” he adds with a laugh. “However” — and it is a significant however — “I do have a long-standing interest in the physiology and biomechanics of playing. And over the years, I’ve become very interested in wellness issues for musicians.”

Eight years ago, Kanengiser co-founded the Musician’s Health and Wellness Committee at Thornton, which, according to its website, “comprises faculty members from varied disciplines including medicine and health care [and] has identified several wellness priorities for current Thornton students: hearing protection; vocal health; injury prevention and recovery, which includes techniques in ergonomics, exercise, and physical therapy; and mental health, which includes strategies for mindfulness, sleep, nutrition, and self-care.”

Kanengiser says, “It started out as a casual conversation with one of the pianists on the faculty and a physical therapist at the Keck School of Medicine who had gotten a degree in music. We began discussing general issues of musicians and wellness and the need for the medical school to start addressing them. We quickly found that USC was well behind the curve of our competition — our colleagues, I should say [chuckles] — in collegiate music education.” The result was an innovative integration of departments.

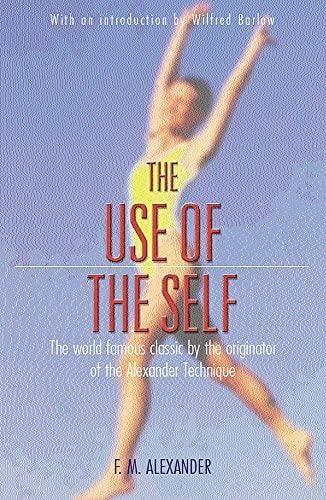

“What we introduced,” Kanengiser explains, “was an entirely new medical group including physical therapists, otolaryngologists psychologists, and others. We started offering physical screenings for musicians and laryngeal screenings for singers. We added auditory screenings for pop musicians as well as a musculoskeletal screening program. At the same time, we offered our students mental health guidance to deal with performance-anxiety issues that emphasized the relationship between mind and body: stretching exercises, the need to take regular breaks during practice as part of injury prevention and recovery. We also introduced a program of body awareness called the Alexander Technique.”

A Guide to Injury Prevention

As described on the website The Complete Guide to the Alexander Technique, AT “is a method that works to change (movement) habits in our everyday activities. It is a simple and practical method for improving ease and freedom of movement, balance, support, and coordination. The technique teaches the use of the appropriate amount of effort for a particular activity, giving you more energy for all your activities. It is not a series of treatments or exercises but rather a reeducation of the mind and body. The Alexander Technique is a method which helps a person discover a new balance in the body by releasing unnecessary tension. It can be applied to sitting, lying down, standing, walking, lifting, and other daily activities.”

In an introductory article to the method, Joan Arnold writes, “An Alexander Technique teacher helps you see what in your movement style contributes to your recurring difficulties — whether it’s a bad back, neck and shoulder pain, restricted breathing, perpetual exhaustion, or limitations in performing a task or sport. Analyzing your whole movement pattern — not just your symptom — the teacher alerts you to habits of compression in your characteristic way of sitting, standing, and walking. He or she then guides you — with words and a gentle, encouraging touch — to move in a freer, more integrated way.”

“I am not a qualified teacher,” Kanengiser makes clear. “But I have had multiple sessions and read a great deal on the subject. In the performing arts the practice is particularly helpful for singers, actors, dancers, and more and more for musicians. It focuses on awareness of postural habits — the arrangement of the head to the top of the spine in a balanced and relaxed way. It’s also a holistic, psychological discipline. The goal is poise, expansion, and relaxation that results in more fluid, balanced, natural movement.”

The bottom line is that musicians, like professional athletes, work very hard, and it takes a toll on their bodies.

Kanengiser explains, “As a segment of the general population, musicians, by many orders of magnitude, are [more] likely to suffer an occupational injury that keeps them from doing their work for an extended period of time.”

And though he has been reluctant to talk about it until now, Kanengiser suffered through his own battle with focal dystonia. And he won.

“About 13 years ago, I started developing symptoms of focal dystonia, which in a way led me on this holistic path. It took quite a few years with setbacks and frustration, but I can say, proudly, I am playing better now than I did before I had the symptoms. There are still tiny things that are amiss. But there are things that I never thought would be possible that I can do now. Essentially, I gradually and methodically re-plasticized my neural pathways. Things have changed a lot from 30–40 years ago, when focal dystonia was considered a death sentence to one’s musical career.”

The Risks of the Job

“I don’t know if there are any companies that offer it, but you should be able to buy Wagner insurance.”

That’s the opinion of Los Angeles Opera Orchestra violinist Lisa Sutton.

“People don’t think about what’s it like playing a four-hour opera in the cramped seating of an orchestra pit as opposed to [in] an onstage concert orchestra. It’s very crowded down there, especially for the big operas like Wagner. And it’s not just the seating where you can barely move your legs. There have to be shields between us and the brass. And it you’re an oboe player, you’ve got a trumpet bell right in the back of your head — it’s not surprising pit musicians suffer hearing loss. But there is nothing more body killing than Wagner. I know string players that have performed Ring cycles and suffered injuries they’ve had to deal with for the rest of their lives.”

Asked whether she saw a comparison between professional musicians and professional athletes, Sutton’s response was revealing.

“Musicians,” she said, “are small-muscle athletes. [We] have a similar relationship with [our] bodies. But at the same time, we have a much longer career trajectory. The most successful professional athletes have sponsors and a team of physicians and trainers to keep them going. We don’t have that unless we seek it out, and we often pay for it ourselves. Truthfully, there are times when playing in the pit feels more like we’re laborers.”

Sutton, who began studying the violin when she was 6, can’t count the many recitals, orchestra concerts, and notes in the millions she’d played before she even began her professional career.

“I didn’t have a teacher who focused on proper body positioning, the type of thing the Alexander Technique emphasizes. I didn’t discover that until I was a professional player in my late 30s and began to have physical issues. When I discovered the Alexander Technique, I had to change my hand, arm, and body positioning. I changed my bowing technique and tried using different shoulder rests. Most people wouldn’t think of it, but I had to change the way I sat during rehearsals. Now, whenever we take a break, I go through a mental checklist. Am I keeping my shoulder down? Am I remembering to breathe properly? Am I sitting properly? How is my weight distributed? Another thing is learning to warm up properly, not just dive into playing something.”

Then, Sutton suffered a condition the Alexander Technique had no remedy for — osteoarthritis. She had to make a choice, she recalls, to end her career or undergo an experimental surgery that would replace two finger joints in her left hand with PyroCarbon joints. She chose the surgery.

“It took me two to three years to regain full flexibility and muscle memory. But I did, and I’m still playing. Now I’m considered the poster child for that operation,” Sutton adds proudly.

East Meets West

Solving the onset of focal dystonia, both Mason and Kanengiser agree, will combine Western medical procedures and medication with Eastern spiritual wellness practices that recognize body and mind are one.

To this end, says Mason, “we need to take a holistic approach that blends Eastern practices such as yoga, acupuncture, meditation, and the body adjustment practices of the Alexander Technique and combines them with Western medical techniques that include the use of neuroimaging and neurophysiologic biomarkers to improve the delivery of DBS [deep brain stimulation].”

At the same time, Mason adds realistically, “the prognosis is not always good. The majority of musicians who show symptoms will have to stop playing. That’s what makes it so horrifying. But with proper treatment, lifestyle redesign, occupational therapy, and counseling, as many as 70 percent of patients could see improvement.”

Mason is also hopeful that as the clinic’s outreach expands to draw from a larger number of musicians in Los Angeles and California, the possibility of finding a complete cure for focal dystonia could be attainable.

Correction: As originally published, this article stated that violinist Lisa Sutton had surgery to replace two knuckles. It was, in fact, her finger joints. We apologize for the error.