A master teacher and prominent musician who had vital connections with Bay Area organizations and found widespread activity and fame around the world, violinist Jorja Fleezanis died on Saturday, Sept. 10 at age 70.

San Francisco Symphony Music Director Laureate Michael Tilson Thomas responded to the news: “I am so saddened to learn of Jorja Fleezanis’s passing. She was one of the most sophisticated, devoted, and omnivorously curious musicians I have ever known. She had a beautiful attitude about life and music and always found the best way to motivate her students and her colleagues to make beautiful music together. She will be profoundly missed by so many.”

SF Symphony Interim CEO Matthew Spivey said: “The passing of Jorja Fleezanis is a tremendous loss for the orchestral community. She was a renowned teacher and an inspirational colleague to her fellow musicians here at the San Francisco Symphony. But I will remember her most as the soloist and creative partner to John Adams for his Violin Concerto, one of my favorite works for the violin.”

Artistic Directors David Finckel and Wu Han, speaking “for the Music@Menlo family,” responded to the news: “Jorja Fleezanis gave her heart and soul to Music@Menlo from the moment she arrived at the festival’s pilot event in 2002. Her artistry, dedication, curiosity, and infectious sense of humor permeated our project, breathing into it the kind of energy that has fueled and guided the festival ever since.

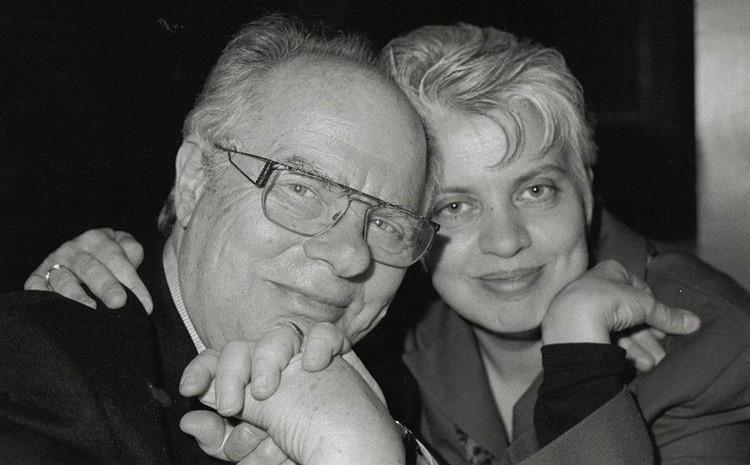

“She inspired her colleagues, moved her listeners, and set an example of artistic excellence [that] has never been exceeded. Along with her late husband Michael Steinberg, Jorja will be forever remembered as a founding pillar of Music@Menlo, upon which the festival still rests, drawing eternal sustenance from her extraordinary spirit. Today, we are filled with endless gratitude for her friendship and generosity and with deep sadness at her passing.”

The daughter of Greek immigrants, Fleezanis grew up in Detroit and attended Cass Technical High School, the Cleveland Institute of Music, and Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

Her prominent, half-century-long career began with a position in the Chicago Symphony. Then, she became associate concertmaster with the San Francisco Symphony for eight years, eventually leaving to the take the role of concertmaster with the Minnesota Orchestra, a position she held from 1989 to 2009. She was only the second woman in the U.S. to hold the title at a major orchestra when appointed and completed the longest tenure as concertmaster in the ensemble’s history.

A highlight of her career there was premiering John Adams’s Violin Concerto, commissioned for Fleezanis by the Minnesota Orchestra, with conductor Edo de Waart leading the first performances in 1994.

While with the Minnesota Orchestra, Fleezanis was named an adjunct faculty member at the University of Minnesota School of Music. Throughout her career, she held guest artist and teaching roles — with the San Francisco Conservatory of Music (1981–1989), the New World Symphony (1988–2017), the Round Top Festival Institute in Texas (1990–2007), Music@Menlo (2003–2008), Music Academy of the West (2013–2022), and also Boston Conservatory, The Juilliard School, Interlochen Arts Academy and Summer Camp, and the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music.

Fleezanis was married to music critic Michael Steinberg, who died in 2009. She had established a fund in his honor. Interviewed by Steinberg on a St. Paul Sunday program, Fleezanis talked about violins:

“Mine is a Lorenzo Storioni from the 1780s, but I’ll be using [at a Beethoven recital] other strings — a gut-wound Oliv G, a gut-wound Eudoxa D, and gut A and E. Actually, I’m not completely sure about the A, that may turn out to be gut-wound as well. My guru on these matters is Andrew Dipper, a wonderful English luthier who works in the Claire Givens shop here in Minneapolis.

“This is a slippery issue, this matter of gut strings. I love the color vocabulary they allow, but I’m also aware that even in the early 19th century there were players who were dissatisfied with them and frustrated by their breakability and by the difficulty of keeping them in tune and who were therefore experimenting with wound strings.

“You could almost say that the whole of the 19th century and the first half the 20th was one gigantic transitional and experimental period. As for the bow I’ll be using, it’s early 19th-century English. One tricky thing is that much of the time while these Beethoven concerts are going on, I’ll be having to do my regular orchestra job with the likes of [Olivier] Messiaen’s Turangalîla, which means that I might be getting a little schizzy.”

Violinist Gaia Ramsdell said of Fleezanis: “She completely changed my life, and reading through all the posts and messages, I’m struck by just how many more musical lives she changed, just how many people and musicians [exist] who would truly not be who they are without her influence and guidance.

“Our private studio at [Indiana University] was always small because every single Jacobs student enrolled in orchestra was also a student of Jorja’s. You couldn’t be in a musical room with her in it without learning from her, getting alternately inspired or lovingly pestered by her to do better — she noticed everything. It always made me laugh at the beginning of a school year to see her in orchestra rehearsal, poking her bow at some new student and whispering, ‘You’re not watching here!’ or ‘Wrong part of the bow!’ and the student’s totally bewildered expression as to who she was or what was happening.

“I’ve never met anyone as committed to anything the way Jorja committed herself to music and to teaching musicians. She taught me the true meaning of commitment, that if you were going to bother to learn a piece, that meant learning to devote yourself to every single phrase, to every single beat, to every single marking and every single rest on that page. (‘FEEL the rest,’ she would say. ‘ְIt’s not just empty space, there’s MUSIC going on here.’) Jorja was adamant that music making did not exist in a vacuum — music was art, and art was everything, the very expression of life itself; she was always finding new ways to teach us that.”