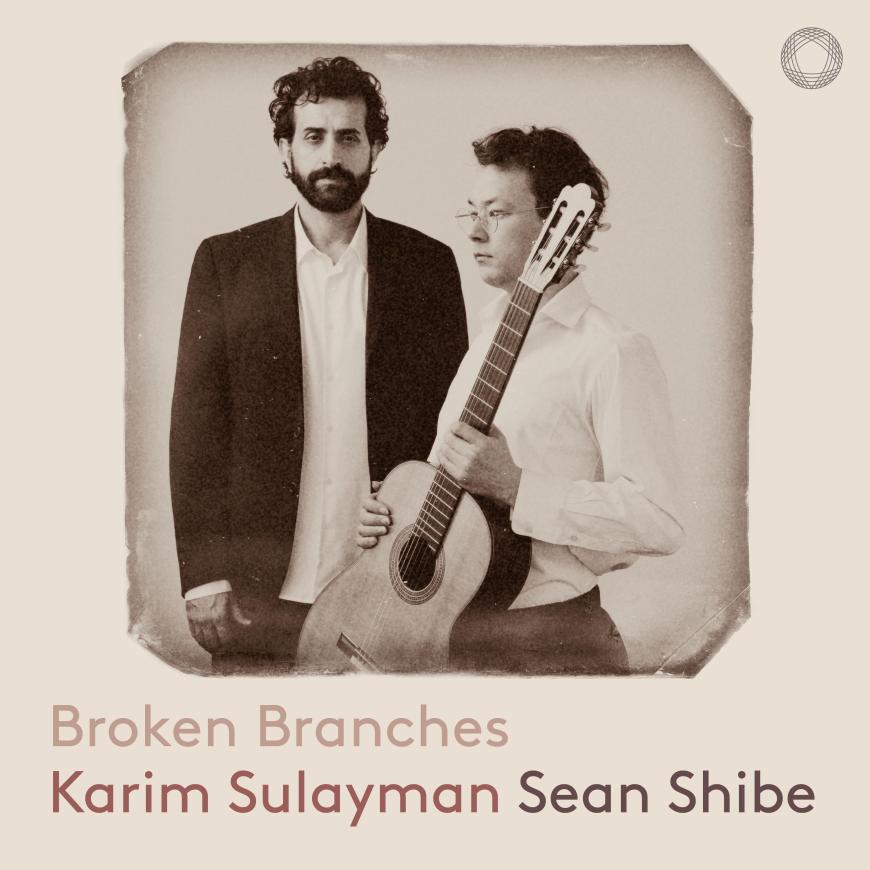

In an era of extreme questioning of both context and content, Lebanese American tenor Karim Sulayman and Japanese English guitarist Sean Shibe present a recording, Broken Branches (Pentatone), that poses more questions than answers. The performers, who met a decade ago as students at the Marlboro Music Festival, question the concept of home when one’s roots are in vastly different and sometimes warring cultures.

In one of the album’s selections, “A Butterfly in New York” — a song by Layale Chaker that Sulayman and Shibe commissioned for the album — the pair illuminate the splintering of family trees between countries and cultures. In their arrangement of Benjamin Britten’s Songs From the Chinese, which sets inaccurate translations by Arthur Waley, they also explore ways in which Western composers have handled orientalist tropes and Asian identities and give examples of cross-cultural musical pollination and wholesale borrowing. They also grapple with solutions, as in substituting a guitar for a lute in some of the culturally problematic selections.

For music lovers who do not necessarily share the artists’ perspectives, a major question arises: Do you listen to the recording’s 16 tracks, from composers as diverse as John Dowland and Sayed Darwish to Claudio Monteverdi and Tōru Takemitsu, while keeping these questions in mind? Or do you instead sit back and simply absorb these beautiful and sincere accounts of diverse and sometimes cross-pollinating repertoire? You’ll have to listen to decide.

For his early-music performances (Dowland, Monteverdi, and Giulio Caccini), Sulayman adopts a lovely, sweet tone imbued with sincerity and, to some extent, innocence. Shibe, in turn, one-ups the traditional lute accompaniment with an unexpected sound that adds a different dimension to the music. Caccini’s “Dalla porta d’oriente” (From the gateway of the East), for example, is nigh irresistible for its combination of vocal earnestness and instrumental spiritedness.

Instead of performing the early-music pieces as a distinct set, however, Shibe inserts Jonathan Harvey’s 1997 instrumental Sufi Dance after Dowland’s “Time Stands Still.” Think about that for a minute. As much as the move comes across as a bit of a curve ball, it also serves as a cultural disruptor that draws attention to Caccini’s commentary on an Italian’s anguished love for a Turkish girl.

The album shifts gears once again with arrangements of a traditional Sephardic song and a traditional Arab-Andalusian instrumental. In “La prima vez” (The first time I saw you), both artists touch deeply on love’s mysterious melancholy, and in Shibe’s guitar setting of “Lamma bada yatathanna” (When my love appeared), feelings of longing and sadness coming to the fore. These are beautiful performances.

The energy picks up considerably in Darwish’s “El helwa di” (That sweet one), a song that speaks directly to Sulayman’s background. There are undoubtedly rawer performances of this music, but the tenor nonetheless draws you in with his changes of tone and color, as well as his imitations of a rooster’s call.

Fairuz’s “Li Beirut” is the vocal and spiritual center of the album. Sulayman’s heart opens when he sings lyrics by Joseph Harb that read (in translation), “The wounds of my people have blossomed / The tears of mothers have blossomed.” Shibe intentionally remains soft and understated, allowing Sulayman’s feelings to sink deeper.

“A Butterfly in New York,” Chaker’s English-language setting of Arabic text by Sinan Antoon, updates the musical idiom to the present day. It’s also a selection that exposes the seeming limits of Sulayman’s range, revealing some strain at the top. That strain resurfaces in some of Britten’s six Songs From the Chinese as well.

Here, Sulayman is at a distinct disadvantage. Britten composed this cycle in 1957 for his lover, tenor Peter Pears, and guitarist Julian Bream. Sulayman has neither the security and force nor the particular mixture of eerie sickliness, decay, and emptiness that make Pears’s recordings of “The Autumn Wind,” “Depression,” and “Dance Song” so powerful. Sulayman’s performances are far more attractive from a timbral perspective — one imagines the “lovely lady” in “The Autumn Wind” would be more drawn to his voice than to Pears’s — but Pears brought another dimension altogether to these songs.

So, a mixed bag, but a valuable one. For the beautiful singing in some of these selections, I hope to return often.