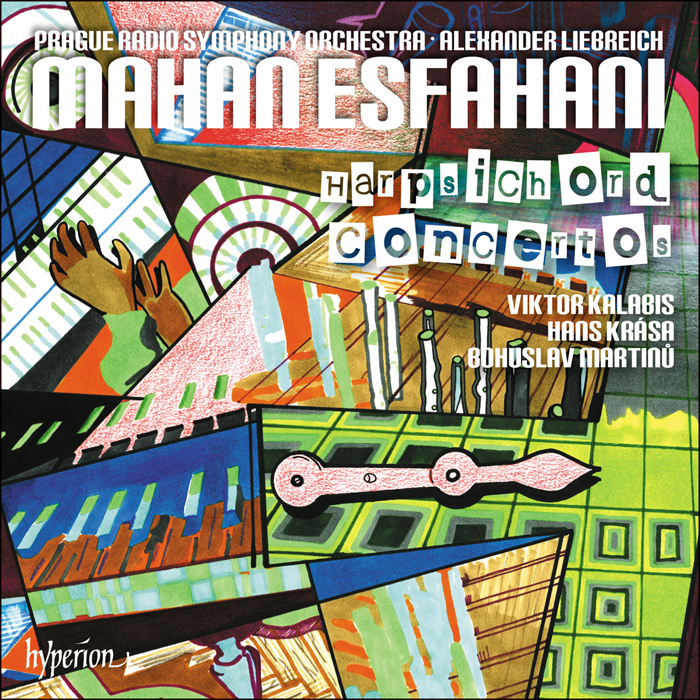

The latest recording release from harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani — iconoclast, adventurer — contains three tasty mid-20th-century concertos for the instrument by Czech composers (Hyperion). Esfahani has been a resident of Prague for the last seven years, so this is not exactly an out-of-left-field project, though the repertoire might be.

Bohuslav Martinů’s Concerto for Harpsichord and Small Orchestra is a neoclassical gem from 1935, bustling with J.S. Bach-derived patterns and cadenzas for the harpsichord and rejoinders from a piano within the ensemble. The term “neobaroque” is actually a better fit — Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 being the most likely throwback reference point — but whatever you call it, this piece has wit, 20th-century bite, and a scurrying coda, a total delight.

The first movement of Hans Krása’s Kammermusik for Harpsichord and Seven Instruments (1936) begins ambiguously but soon embarks on a Paul Hindemith-like path of counterpoint interspersed with frequent changes of style, even hints of jazz in the parts for alto saxophone and muted trumpet. A pop-jazz flavor becomes dominant in the opening tune of the second movement, a sign that Duke Ellington’s influence was seeping into Central Europe before the Nazis could crack down. After some energetic activity, the earlier mood returns in a melancholy coda that in hindsight seems to trigger thoughts of foreboding developments just around the corner.

Viktor Kalabis (1923–2006) is the least known of the three composers, but to Esfahani, he was practically family because Kalabis’s wife, the renowned Czech harpsichordist Zuzana Růžičková, was Esfahani’s teacher and he her last student. The first movement of Kalabis’s Concerto for Harpsichord and String Orchestra (1975) sounds as if it is directly descended from its neoclassical predecessors on the recording until a harpsichord cadenza slows everything down to a virtual halt. The second movement is stern, stark, with big spaces between harpsichord chords, ultimately hinting at some form of deep personal tragedy. The third movement pulls things temporarily out of the doldrums with a lot of rapid modernist keyboard chatter before descending into doubt again.

Esfahani is steel-fingered, precise, non-indulgent, aware of the humor that pops up, and gets terrific support from various configurations of members of the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra as led by Alexander Liebreich. The sound is excellent, as it usually is on Hyperion — deep and rich, making these bands of players seem bigger than they really are.

Hopefully, this release will not be among the last to bear the Hyperion logo, for the defiantly independent British label was just sold to the Universal Music Group behemoth on March 15. While Universal’s statement promises to keep Hyperion as is — and at the very least, it’s likely to give the label much greater distribution — one only hopes that Hyperion can somehow retain its identity and keep its catalog in print because several other labels prized by music lovers have either disappeared or been altered in mission within the corporate labyrinths of the big three (Universal, Sony, and Warner).