Jordi Savall, a superb gambist and a performer committed to the political and historical implications of music, presented his newest collaborative program Saturday night at Cal Performances, to a packed and enthusiastic audience.

Titled “The Routes of Slavery: Memories of Slavery (1444–1888),” the program concentrated on the enslavement of African peoples, though (in spoken and written comments) Savall emphasized that slavery has touched many other cultures, from the defeated enemies of the ancient Greeks to today’s sweatshop and sex workers.

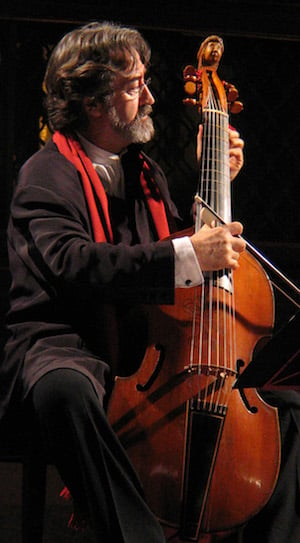

Savall took a seat at the side of the action, literally and figuratively, occasionally conducting with his viola da gamba bow, and only once or twice demonstrating his virtuosity as a player — notably in a set of “divisions” on a popular song tune. The large ensemble he has assembled is diverse: five singers of La Capella Reial de Catalunya (dedicated to performing historical music from Catalonia); Hespèrion XXI (Savall’s usual instrumental ensemble); Tembembe Ensamble Continuo (specializing in Hispanic baroque music and based in Mexico, comprising performers from Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, and Guadeloupe); and five Malian singer-instrumentalists.

Among many fine performers, the stand-outs were Ballaké Sissoko playing the kora, a plucked Malian instrument; Mohamed Diaby in the role of a griot (a West African praise-singer and storyteller); and the Canadian soprano Neema Bickersteth, who delivered several American slave songs with stunning focus and dignity.

The music ranged from slave songs to Malian epic ballads. Many of the larger ensemble pieces were anonymous late-medieval and Renaissance songs from the countries of the Hispanic slave trade. English translations of the lyrics were projected as supertitles, but the printed program, which identified pieces, languages, and origins, was impossible to follow due to Cal Performance’s insistence on turning off all the house lights. This policy has interfered with a number of presentations I have attended in Zellerbach Hall, and should be changed.

Interspersed among the musical selections was a selection of slavery-related documents from the 15th century to the present, including graphic descriptions of the capture, sale, and punishment of enslaved people, as well as legal documents about slavery. These historical witnesses to the evils of slavery culminated in more modern documents: a personal letter of Abraham Lincoln, the 13th Amendment to the U. S. Constitution, and the Nobel Prize address of Martin Luther King. Aldo Billingslea, professor of theater at Santa Clara University, delivered the complex rhetoric of these documents with insight and unflinching commitment to their often-appalling perspectives.

Making a coherent program with such a global collection of musicians is an enormous challenge. These performers seemed to thrive on the diversity of the music, joining together in the music across national and stylistic borders. A singer from Catalonia harmonized on an American slave song; European recorder players joined African instrumentalists; harp, guitar, and kora jammed together with a multitude of drums and percussion instruments (including one that looked like the jawbone of a large animal).

If the musicians seemed to appreciate the chance to work together, as a listener I found it difficult to follow the rapid shifts of historical and geographical style. Too often I was left guessing what language, what musical tradition, and what historical period was being presented. I was particularly baffled — and still am — why many of the songs seemed to be about the baby Jesus, hardly an obvious topic for a program about slavery.

In his printed notes and spoken comments at the end of the program, Savall acknowledged the many contrasting aspects of slavery — the suffering of slaves and the hopes of survivors, the legacy of evil and the heroic histories of resistance. The evening itself embodied these contrasts: the spoken narration dwelt on the harsh fates of individual enslaved persons, subject to brutal political and economic realities; the music, by contrast, tried to mitigate these realities — in Savall’s words, to be “an eternal refuge of peace, consolation and hope.”

But while the performances were energetic and often upbeat, that wished-for hope came across only in bits and pieces. The history of slavery — repeatedly and unflinchingly recounted by the narrator — was so brutal that each successive plunge back into the music seemed tentative and confusing.

This was an ambitious venture — rightly, for the intractable legacy of slavery and the concomitant curse of racism are enormous problems. But the project took on too much for one evening of performance, often overwhelming where it hoped to inspire, and fragmenting where it hoped to bring together.