James Conlon’s “Recovered Voices,” that laudable attempt to resurrect the works of persecuted and/or neglected composers from the 20th century, is back in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion at last.

The project originally bore fruit in the first decade of this century with five LA Opera productions, three of which were preserved on DVDs, a fourth making it onto CD. But the funding ran out, and though there have been some less-ambitious projects at the Colburn School and elsewhere, nothing has appeared on LA Opera’s main stage since 2010’s gorgeous production of Franz Schreker’s Die Gezeichneten.

With its resurrection Saturday night (Feb. 24), “Recovered Voices” has undergone a bit of a makeover, extending its mission to include Black composers who have felt the lash of prejudice American style. Hence this Conlon-led double-bill of William Grant Still’s Highway 1, USA coupled with a revival of the 2008 production of Alexander Zemlinsky’s Der Zwerg (The Dwarf).

An odd-couple, indeed; two one-act operas whose composers seemingly had virtually nothing in common aside from both having experienced persecution and the coincidence of having set texts by Langston Hughes at one time or another. But if one suspends notions of linking the settings and musical syntaxes of Highway 1 and Der Zwerg, it becomes apparent that both operas are fascinating in their depictions of human nature. Family loyalty, insecurity, jealousy, and the aspirations and barriers to a better life are among the issues that pass through the Still opera, and vanity, self-delusion, unconsciously callous cruelty, and ultimately heartbreak play out their parts in the Zemlinsky one-act. Neither work is perfect, but both pack an emotional punch.

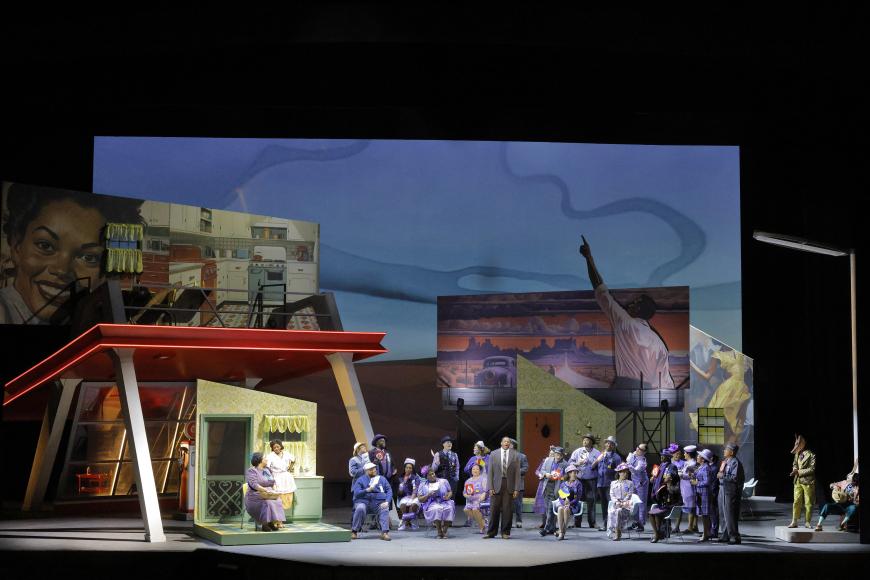

For Highway 1, USA — meaning U.S. Highway 1 which runs the length of the Eastern seaboard — director Kaneza Schaal has placed the action sometime in the 1950s, halfway between the opera’s conception in the 1940s and its belated premiere in 1963. The neon-light-rimmed architecture of the gas station that Bob (Norman Garrett) and his wife Mary (Nicole Heaston) operate is startlingly evocative of its period, as is the modest apartment and drab kitchen in which they live. Bob’s character is especially well-drawn; he’s a good guy of modest self-esteem, grateful that someone as kind as Mary would accept him as a husband, faithful to his dying mother’s wishes that he look after his younger brother Nate, but blind to his sibling’s self-serving faults. While Bob’s willingness to take the blame for the crime that Nate commits stretches credulity beyond the breaking point — no one’s that good-hearted — he learns his lesson about his brother pretty quickly thereafter.

If any work comes to mind upon hearing Highway 1 for the first time, it is Kurt Weill’s Street Scene (which happens to have a Langston Hughes libretto), another example of a theater piece dealing with a slice of ordinary American mid-20th-century life. It’s American verismo of the period, one that mixes streams of European opera, especially Puccini, into the domestic musical language. Still’s score is often lush and Romantic, especially when husband and wife sing duets, and the only times when his vernacular style enters the picture are when the chorus of neighbors — often dressed in shades of purple — add just a whiff of jazz. Highway 1 is also neutral in another striking way; there are virtually no hints of race issues in the plot. Bob and Mary are striving for a better life, and it doesn’t matter what color they happen to be.

At first, Garrett and Heaston, the two leads, were difficult to hear over the orchestra; it could be that the design of the set or my seat location in the acoustically-spotty Pavilion were at fault. But later on, as the scenes changed and the singers moved further up front, Garrett’s pleasant baritone and Heaston appealingly impassioned soprano could be heard more clearly. Mezzo-soprano Deborah Nansteel made a sympathetic Aunt Lou and tenor Chaz’men Williams-Ali affected a weak-sounding Nate that fit the part. Two mute characters prompted by mentions in Verna Arvey’s libretto — a Fox (Kiara Benn) and a Hare (Cheyanne Williams, who also co-designed the scenery) — kibitzed, moved the scenery around, and tried to stay out of the way.

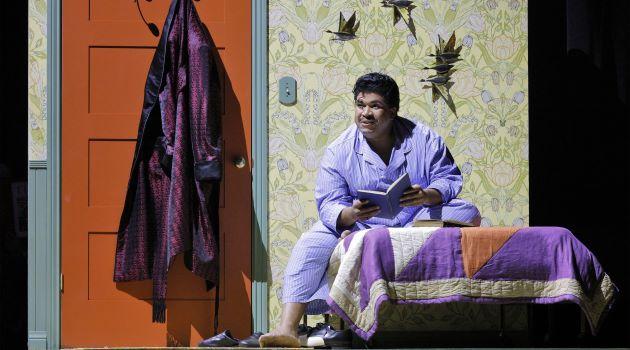

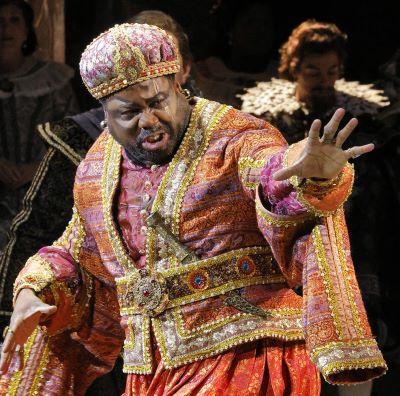

Der Zwerg, meanwhile, was a straight-on reproduction of the 2008 performances utilizing the same stage director (Darko Tresnjak), the same gorgeously grand, extremely well-preserved Ralph Funicello Spanish palace sets, the same Dwarf (Rodrick Dixon), and of course, the same conductor. Zemlinsky was the composer of the tone poem Die Seejungfrau, the chance hearing of which on a car radio set Conlon on his never-ending “Recovered Voices” mission.

Conlon’s conducting sounded even more deeply committed to exploiting the plush, complex, post-Romantic Zemlinsky sound, making the lavish Spanish-tinged orchestrations surge, sweep, sparkle, and move with greater degrees of depth and color. You have to hear this live in order to get the full impact of Zemlinsky’s orchestrations; the DVD sound doesn’t quite do them justice even on a good home system. Equally so, with all of its close-ups, the DVD doesn’t give you much of an idea of the grandeur of the set. But it’s good that the recording exists (it can be found on the Arthaus Musik label).

As the Temptations used to sing, “Beauty is only skin deep” — and the opera, based on Oscar Wilde’s original story, The Birthday of the Infanta, exploits this theme with wicked insight. The Infanta, Donna Clara, is beautiful on the outside and ugly on the inside while the Dwarf is exactly the opposite, and therein lies the tragedy that pushes the opera to the limits of high emotion. It may be the most wrenching depiction of heartbreak in the known operatic literature, so the vulnerable should approach with caution.

Though less dwarf-like and more dignified in his physical motions than before, Dixon still sings the role to the hilt, his now-stronger Wagnerian tenor growing more impassioned as the piece goes on. Soprano Erica Petrocelli’s doll-like, wide-hoop-skirted, big-voiced Infanta does a very convincing job of deceiving the Dwarf, bass Kristinn Sigmundsson was a diplomatic Don Estoban, soprano Emily Magee a compassionate Ghita (the Infanta’s maid). One troubling thing I noticed is that in certain moments of pain for the Dwarf and comments of unconcern by the Infanta, the audience reaction was laughter, whereas I remember hearing gasps from the crowd in 2008. Is this due to a general coarsening and desensitizing of our culture since then?

Alas, there is nothing on tap for “Recovered Voices” in LA Opera’s just-announced 2024-25 season, which like most American opera companies is playing things cautiously at a time of diminishing resources. But it’s good to have it back in the spotlight for a while, along with a plethora of satellite events centered around Still and Zemlinsky this month and next.