Ever conscious of being the spearhead of progressive programming among major symphony orchestras, Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic are opening the 2022–2023 season with three more installments of their Pan-American Music Initiative. The series may have been stalled by the pandemic, but it’s rolling now.

Right, but perhaps rolling in a somewhat diluted format. After all, the first program, which was to have been a cavalcade of little-known Mexican, Venezuelan, and Brazilian music, was scrapped entirely and replaced by a taste of John Adams, a lot of Mozart, and Julián Orbón as the sole south-of-the-border representative. The next program, which took place this past weekend, contained a reprise of Gabriela Ortiz’s LA Phil-commissioned violin concerto, Altar de cuerda (String Altar) — first heard here last May — and Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 (the latter qualifying as a Pan-American piece only if Mahler’s brief stay in New York City as conductor of the Metropolitan Opera and New York Philharmonic counts).

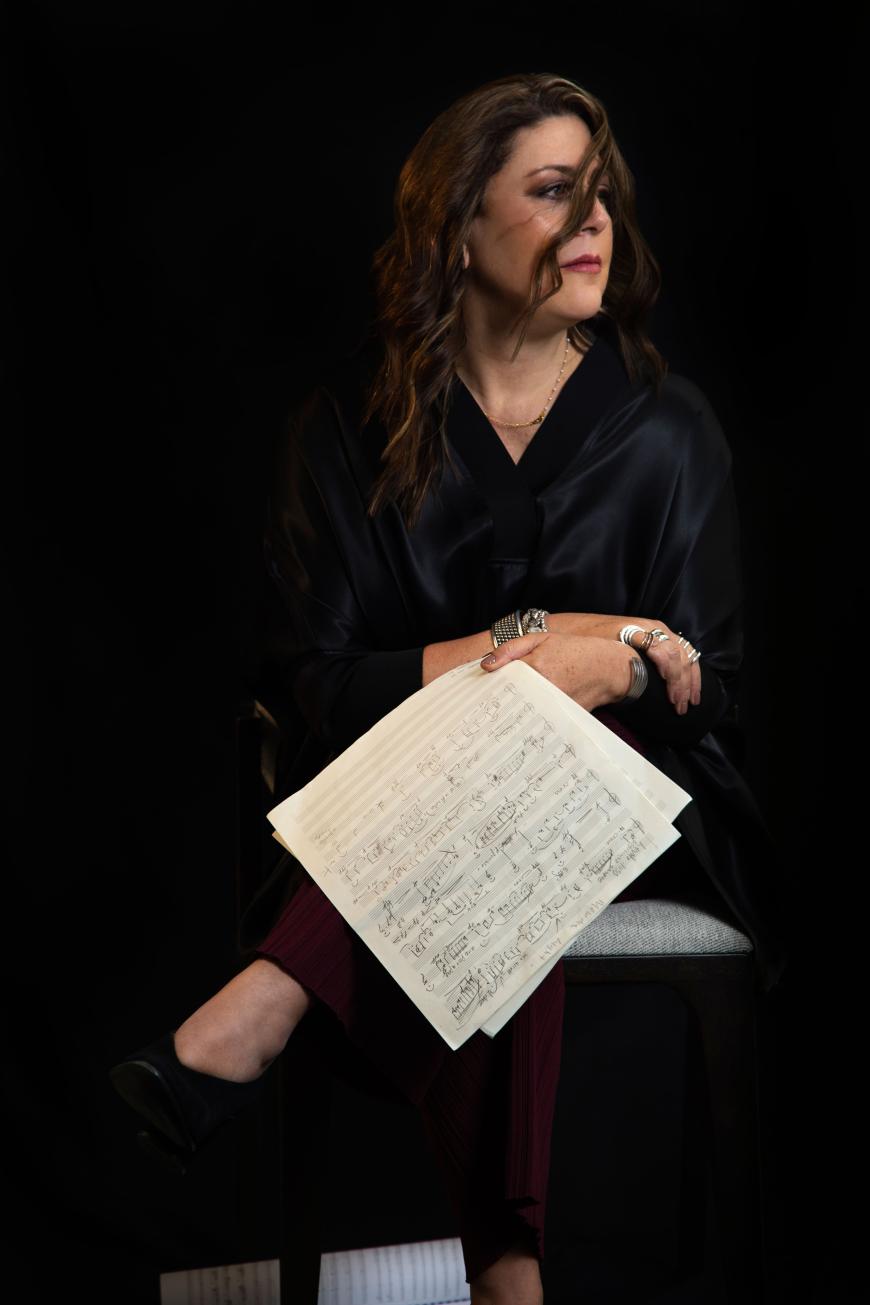

This concert was a hometown preview of the LA Phil’s short tour of the East Coast and Mexico later this month, with the same program being played in Boston’s Symphony Hall Oct. 23, New York’s Carnegie Hall Oct. 25, and in Guanajuato, Mexico, Oct. 29. Also, the Ortiz piece was being recorded for eventual release by Deutsche Grammophon, which still has Dudamel under contract and just signed the concerto’s soloist, the astonishing 19-year-old Andalusian violinist María Dueñas. By introducing new pieces by Latin American composers, getting repeat performances here and on tour, and making recordings of same, the Pan-American Music Initiative is already making some headway.

Fortunately, the three-movement, 32-minute Altar de cuerda not only holds up on second exposure (I caught it Sunday afternoon, Oct. 9), it improves and deepens, aided by the performers’ increased familiarity with the work. In the introductory measures of the first movement, Dueñas’s opening notes really burned, the struck chords gleamed, the visceral impact of it all greater than what memory recalls about the first performance. The second movement is an extended música nocturna dominated by the sheen of the strings, spectacular pitch gliding in the central pages, and brass and wind players creating spooky drones from tuned crystal glasses. Then Ortiz bears down and gives the soloist a jagged obstacle course to run in the finale — which again didn’t seem to faze Dueñas in the least.

The subtext of the piece is about the two-way appropriation of influences as it pertains to Mexican architecture and culture in general. OK, but more directly, the work entices the ear with colorful sonorities, particularly from the harp and mallet percussion, and its razzle-dazzle solo part is making a major star out of the violinist for whom it was written.

If there is any piece that might be considered to be the signature work for Dudamel in Los Angeles, Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 would be a leading contender. It was the choice for his inaugural concert as music director in 2009, and he has programmed it frequently since — most recently in March 2019 — and indeed, the exultant final measures of the finale have underscored ads for the LA Phil during the Dudamel years. And so, here it was again, concluding the concert on a note of guaranteed triumph — or so the automatic standing ovation indicated.

For Mahler buffs who have witnessed most or all of these performances, Dudamel has been tweaking this or that element in the score from year to year. His proclivity toward faster performances of Mahler toward the end of the last decade went into reverse Sunday, for he returned more or less to the slower pace that he established in 2009. Unfortunately, one bad habit from the inaugural concert that he abandoned in later renditions of Mahler’s First has returned — the acceleration from a slow start in the first measures of the opening Ländler theme of the second movement, applied inconsistently in the repeats later. It sounded strange and inorganic then and still does today.

Otherwise, Dudamel’s interpretation went just fine. There was hushed concentration and control in the quiet opening measures leading to the explosion of youthful ardor toward the close of the first movement. The Jewish music in the third movement was smoothed over at first yet acquired the missing lilt later, and Dudamel was at his best in the tempestuous, heart-rending, ultimately blazing finale.

Afterwards, as a pre-tour treat for the home crowd that usually never gets to hear encores, Dudamel rolled out a wild, wonderful, Latin Americanized fantasy on Johann Strauss Jr.’s Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka by Paul Desenne, who calls it “Triqui Traqui.”

Next on the schedule this weekend: at last, a truly Pan-American lineup, with reruns of Ortiz’s Kauyumari and Arturo Márquez’s Fandango coupled with Aaron Copland’s Symphony No. 3. That program also goes to Carnegie Hall Oct. 26.