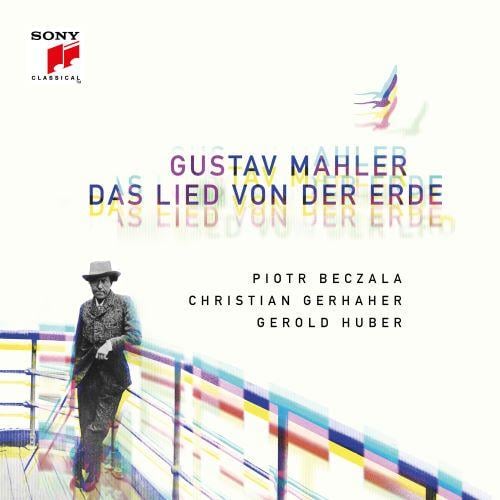

Yes, you’re reading correctly. As much as some have called Gustav Mahler’s hour-plus song cycle Das Lied von der Erde (The song of the earth) the composer’s 11th Symphony, the work exists in Mahler’s sanctioned transcription for voice and piano. According to Peter Gülke’s liner notes for the new Sony recording Gustav Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde, in which tenor Piotr Beczala and baritone Christian Gerhaher join pianist Gerold Huber, the draft for the full orchestral score may predate the version for voice and piano recorded here.

It’s startling to hear the differences. In place of huge sweeps of color, differentiated by pitch and rhythm, we take in myriad, often jarring percussive notes and lines that seem far more radical in harmonic design. It’s as if we’ve been invited to witness a fascinating dissection in which the bare bones of Mahler’s conception are exposed under its smooth fabric.

But this thankfully bloodless experience isn’t at all antiseptic. Beczala and Gerhaher get credit for that. Given how ideal Beczala seems for the tenor part, it’s amazing that he never recorded Das Lied until he was 53 — for this album. You’d almost think him a heldentenor for his ability to ride the demanding high tessitura of his extroverted drinking songs and to sing out strongly without apparent effort. His voice, heavier than at the start of his fame as a lirico-spinto, sounds splendid and filled with exuberance. Don’t miss his soft, high voicing of the line “Mir ist als wie im Traum” (To me it is like a dream) in his final song, “Der Trinker im Frühling” (The drunkard in spring). This is marvelous singing.

Gerhaher, who was almost 51 at the time of the recording, initially recorded Das Lied with Kent Nagano and the Montreal Symphony for a 2009 Sony release. Here, his voice remains fresh, warm, and inviting, although a few of the lowest lying passages dip below the most melodious parts of his voice and a single high passage seems strenuous. In a few instances, he fails to equalize volume where nothing should stand out dynamically. Nor is longing always present in his voice during “Der Abschied” (The farewell). Nonetheless, there are moments where his word painting and phrasing are profound. All in all, it’s a lovely performance.

In the final song, Huber occasionally performs miracles, voicing notes into lines that sound like strings of tears. Other times, the dryness of the piano sound, as captured by Sony’s engineers, limits his poetic impact. Perhaps pandemic-imposed restrictions, which may have led the two soloists to enter the studio with Huber almost four months apart (the album was recorded in 2020), have something to do with the sonics.

Regardless, any Mahler lover won’t want to miss this performance. What you may have once taken for granted in Das Lied will sound instead like you’re discovering the work’s bold harmonic language for the first time. Highly recommended.