The last time Joanne Pearce Martin and Vicki Ray performed John Adams’s “ode to joy” for two pianos, Hallelujah Junction, was at the 2021 Ojai Music Festival. It took place outdoors before an audience still under COVID health protocols, inoculation certified and completely masked.

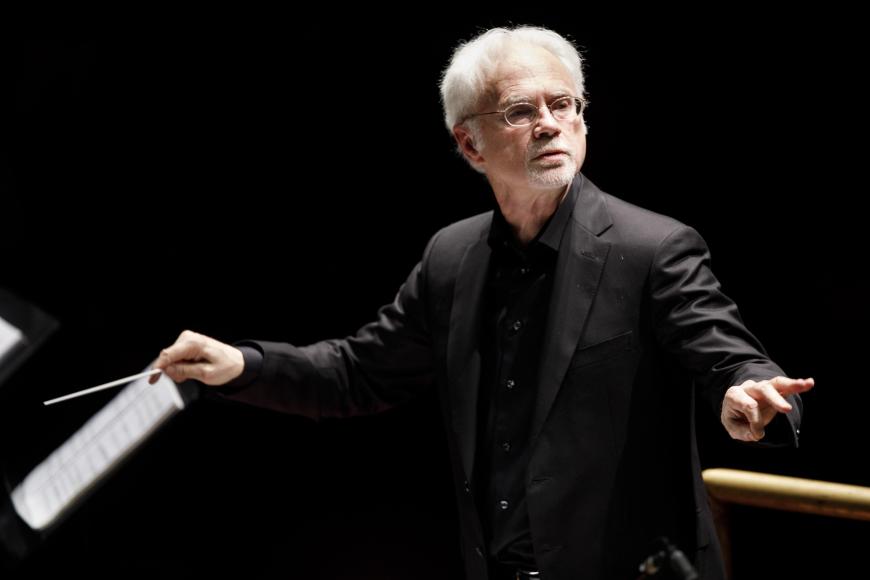

At Walt Disney Concert Hall on Tuesday, Martin and Ray returned to Hallelujah Junction as the climax of a Green Umbrella concert with the LA Phil New Music Group and Adams conducting. It was three years to the day since COVID-19 shut down live performances for a year and a half. But even though the masks were gone and the mood was jubilant, echoes of those dark days lingered and were directly referenced in several of the compositions.

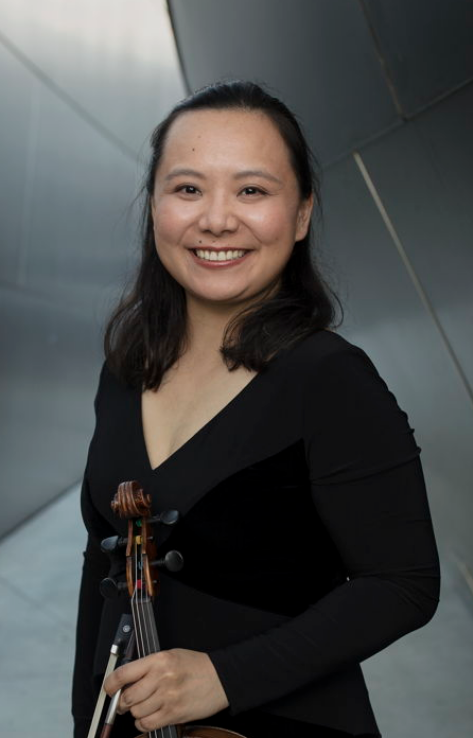

In 2020, sequestered at home, Esa-Pekka Salonen composed one in a series of 10 short “lockdown commissions” for the British violist Lawrence Power, who videoed his performances atop iconic London locations (they can still be seen on YouTube). The Los Angeles Philharmonic’s principal violist, Teng Li, gave the first live performance of Salonen’s contribution, titled Objets Trouvés, at Ojai in 2021 as well.

Tuesday, isolated in a pool of light and accompanied by a prerecorded electronic drone, Li opened Green Umbrella, as rain poured down outside, with a reprise performance that brought back those dark days of isolation and anxiety, just as the darkness of the hall surrounded her onstage.

After the almost inaudible entrance of the drone, the viola attempts to execute a brief figure. Far less than a melody, the motive tries to escape in an ascending gesture, only to be blocked and forced down again and again. Perhaps out of frustration, the gesture turns into a series of rapid phrases in jittery proportions. Eventually out of this conflict comes a resolution in the form of an elegy — the first truly melodic line, one which seems hauntingly similar to John Williams’s plaintive violin theme for Schindler’s List.

During a preconcert talk, composer Anthony Cheung spoke about the process he went through observing his 3-year-old daughter forced to experience early childhood in pandemic isolation, deprived of the socialization of playing with other kids. And when she could finally play, it was under the strictest conditions.

With that in mind, the six sections of Cheung’s Parallel Play (the setup is drawn from sociologist Mildred Parten Newhall’s study of the six stages of child’s play) take on an unusual instrumental dynamic, from isolated self-absorption to paired participation to organized group activity.

Anyone who has kids, or a dog, knows how the most carefully organized room can become a minefield of scattered toys. For Cheung, those toys can be seen in terms of instrumental diversity. Composed for 18 players, the piece boasts a tonal, atonal, and microtonal spectrum that’s expansive, including an overlay of piano, micro-tuned electronic keyboard, and organ. The instruments function as solo voices, paired groups, contrasting clusters, overlays, and collisions.

As the performance conducted by Adams evolved, I found it advantageous to forego the sociological permutations and childhood-play metaphor in favor of a total immersion into Cheung’s complex and sophisticated instrumental interplay and layering. The effect was like being drawn, like Alice, down the rabbit hole.

As Adams pointed out from the stage, the role of improvisation, which once played an important role in classical music, has been all but replaced by exact notation. That is not the case for composer and bassoon virtuoso Katherine Young. Her LA Phil commission Spores was initially composed in 2017, its premiere delayed until Tuesday, first by illness, then by the pandemic.

If there is such a thing as a rock-star electric bassoonist, it would have to be Young. “She’s got more foot pedals than Jimi Hendrix,” Adams quipped.

Young’s title is a reference to the reproductive units produced by mushrooms, some of which have managed to migrate around the globe. Another influence, Young said, was early electronic-music compositions. It makes for a fascinating blend — airborne “spores” in the form of electronics and phasing, plus extended sections of improvisation in which musicians are instructed to listen to what other musicians are playing and then riff on it.

Composed for electronic and acoustic bassoon, assorted brass, winds, strings, and a battery of percussion, including a pairof triangles, the piece is by turns as dense as molasses, as light as air (with the musicians encouraged to vocalize their breath), and as freewheeling as a trip down the open highway.

The instrumental combinations are consistently imaginative, such as a trio of bass clarinet, contrabassoon, and tuba. Then, to spread out the sound at Disney Hall, Young had several of the musicians position themselves in the balconies surrounding the stage. As skillful as Adams’s conducting was, it would have been fascinating to hear the piece performed again to catch the changes in the improvisational sections.

To bring it all to a joyous, rollicking conclusion, Martin and Ray rocked Hallelujah Junction, with Adams in the audience, head bobbing to the beat.