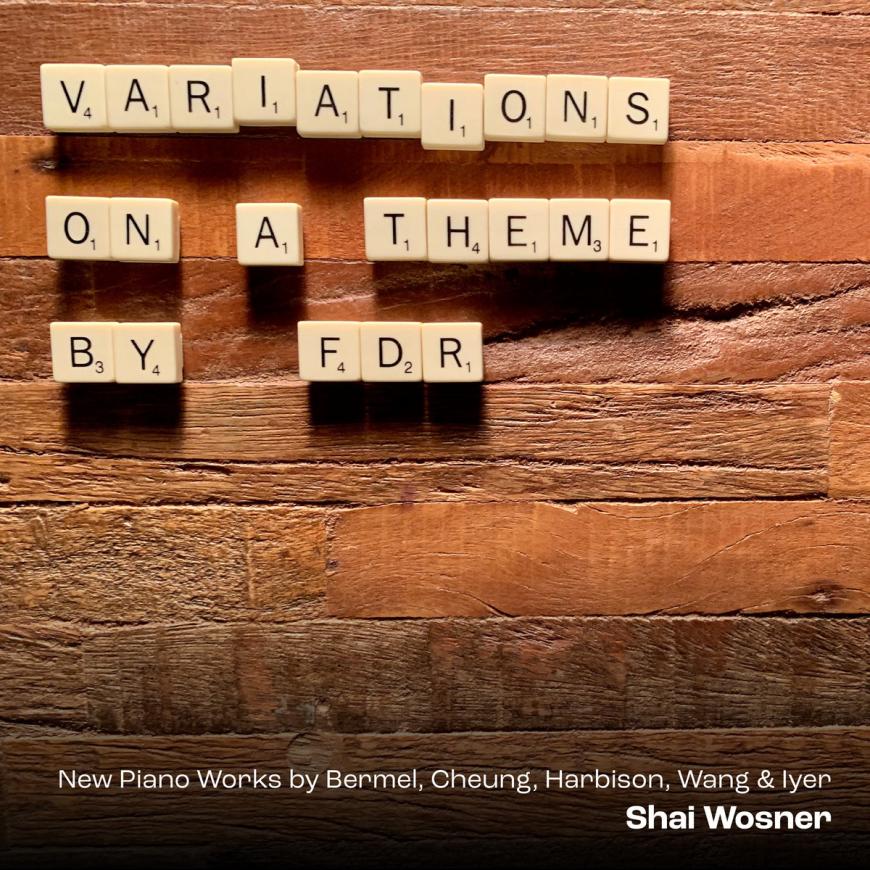

For his latest recording, Variations on a Theme by FDR (New Focus Recordings), Israeli-born, New York-based pianist Shai Wosner took as his springboard a quotation from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1938 address to the Daughters of the American Revolution. In that short speech, which FDR gave a year before the DAR prohibited contralto Marian Anderson from performing in Constitution Hall, he said, “Remember, remember always, that all of us … are descended from immigrants and revolutionists.”

While FDR’s statement, on face value, is incorrect — Black Americans almost exclusively arrived in America as slaves rather than immigrants and were treated very differently from white immigrants and revolutionists — the quote reflects the good intentions of a president who would then turn his back on the DAR and, with his wife Eleanor, arrange Anderson’s historic concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The statement also motivated Wosner to invite five contemporary American composers — Derek Bermel, Anthony Cheung, John Harbison, Vijay Iyer, and Wang Lu — to write variations on FDR’s theme. (In recital, Wosner pairs these variations with Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations.)

A joint commission of Peoples’ Symphony Concerts in New York City, where Wosner is the 2020–2024 artist-in-residence, and the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, the five Variations on a Theme by FDR together run a little over 31 minutes. While that may seem short shrift for a very well-recorded CD, all proceeds from the sale will be donated to Team TLC NYC, a volunteer organization supporting asylum seekers and immigrants.

Each composer took inspiration from the story of an immigrant of his or her choice. If I begin with the last and longest work, Vijay Iyer’s “Plinth (for Kwame Ture),” it is because I have a strong relationship with the words and deeds of the Trinidad-born Ture, aka Stokely Carmichael (1941–1998). Ture, who participated in one of the early Freedom Rides and later served as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, articulated the notion of Black Power as “a call for Black people to define their own goals, to lead their own organizations.” Carmichael’s call came less than a year after I spent most of the summer of 1965 as a voter registration volunteer in Williamston, North Carolina, with Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Even before the program had ended, this white grandson of Russian-Jewish immigrants came to the realization that I had the potential inadvertently to do more harm than good.

Iyer’s work begins with dark and insistent churning. To my mind, it speaks of Ture’s resolve to stick to his message and engage wholeheartedly in the struggle for freedom. As long-lined arpeggios run up the keyboard, I imagine him stretching his wings and expanding his reach. The struggle itself is portrayed with jazz-like aplomb.

The New York-born Bermel intended his “Pequenas Memórias” (Small memories) as a tribute to the journey of his Lisbon-born wife, Andreia Pinto Correia. It is also the title of Portuguese writer José Saramago’s memoir. It’s the most lyrical piece in the Variations, with a lovely childlike quality that’s quite fetching. To Bermel, the music describes the challenges of an immigrant who overcame a traumatic accident to experience creative rebirth as a composer.

“Bitter Seas” by the San Francisco-born Cheung is equally quixotic and compelling. It is a short homage to South Korean-born, San Francisco-raised artist and writer Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951–1982), whose work explored “themes of cultural memory, trauma, and erasure.” The title refers to a work Cha created in 1976, in which an American flag is stamped with the French word amer, which translates as “bitter” or (as à mer) “to the sea.” Cheung’s music seems to describe a struggle in which an immigrant can never fully establish herself or gain a solid footing. It ends without resolution.

The New Jersey-born Harbison, one of several composers in the collection with a connection to Harvard, wrote his “Passage” to describe the transformation of Russian immigrant Vladimir Dukelsky (1903–1969) to composer Vernon Duke, a well-known contributor to the Great American Songbook. Harbison’s interest in Duke stems from the summer of 2004, when he stayed in the home of Duke’s widow. At times, one can sense a bit of swing, a touch of Duke’s music, or a smattering of café-like atmosphere. It’s an intriguing piece, excellently recorded, that further recommends Wosner’s creative album.