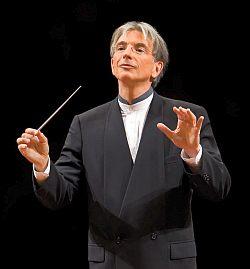

With the two Stravinsky works serving as bookends for the program, Wednesday’s performance, which repeated through Saturday, also featured Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major. Aside from a linear connection — the concerto being a jewel of the Classical repertoire, and Pulcinella the piece that ushered in the Neoclassical phase of Stravinsky’s career — the Mozart performance, which featured Tilson Thomas as leader and soloist, proved more of a distraction than an enhancement. More on that later.

The evening’s chief reward came in the second half’s sparkling performance of Pulcinella. Composed for Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, the 1920 score remains a marvel of recomposition: There’s something eternally delicious in the way Stravinsky took fragments, melodies, and entire earlier works by Pergolesi and his contemporaries (Gallo, Monza, and Parisotti included) and fashioned them into something his own. The composer, who didn’t care much for Pergolesi’s music until he started this project, “fell in love” with his sources; Pulcinella looks back to the 18th century with great affection, and anticipates the 20th with genius.

That gift of invention was clearly audible Wednesday, as Tilson Thomas led the Symphony’s first return to the complete score since 2003. The orchestra played with zest and responsiveness in the central theme and variations, and the score’s smaller episodes, which range in mood from ardent to bitingly acerbic, were keenly articulated. Concertmaster Alexander Barantschik contributed rustic violin solos, and principal oboist William Bennett played the oboe part with his customary finesse.

The vocal soloists were uniformly strong. Mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke, returning from last year’s S.F. Symphony debut in the starring role of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe, sang with fluent, luscious tone in the showpiece aria “Se tu m’ami.” Bruce Sledge brought an admirable measure of heft to the tenor part, while Eric Owens anchored the trios with his large, resonant bass.

A Performance to Cherish

As for Octet, a Stravinsky aficionado could wait a lifetime to hear a performance as lithe and shapely as the one that opened the program. The 1923 score, for woodwinds and brass, is unusual in its instrumentation, rhythmic variety, and harmonic language, and performances are rare — the Symphony last played it during the 1999 Stravinsky Fest. Here, the orchestra’s Tim Day (flute), Luis Baez (clarinet), Steven Dibner (bassoon), Rob Weir (contrabassoon), Mark Inouye and Jeff Biancalana (trumpet), Timothy Higgins (trombone), and Jeff Engelkes (bass trombone) made a formidable ensemble, negotiating the work’s skittering rhythms, jaunty melodies, and ungainly waltzes like a team of downhill racers. Playing without a conductor, they gave a superb performance; taking their bows at the end, all eight musicians were beaming.In between, the Mozart concerto registered as a miss. Tilson Thomas has taken on soloist duties with the orchestra in past seasons with fine results, but this performance sounded patchy and under-rehearsed. Leading from the piano, he launched into the work with high spirits, but things went awry almost immediately. Rushed entrances, slurred notes, and a general feeling of rhythmic shapelessness marked his playing; the outer movements were uncoordinated, while the central Adagio, with its air of tragic resignation, sounded oddly slack. The orchestra played along gamely, and Tilson Thomas seemed energized by the solo opportunity. Still, exuberance didn’t compensate for lack of precision.