Some 15 different operas will be shown on Bay Area screens this fall, with productions emanating from five European opera houses and the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.

Opera lovers can see the precedent-setting and brilliant Valencia Ring cycle in its second installment, Wagner’s Die Walküre, and Bartlett Sher’s new production of Offenbach’s Contes d’Hoffmann with Anna Netrebko. Never been to La Scala? You can hear and see its production of Monteverdi’s Orfeo. Dreamed about going to Salzburg to see an opera? Watch its production of Mozart’s masterpiece Così fan tutte on Nov. 8. Want to see why audiences booed the Met’s new production of Tosca? Find out on Oct. 10.

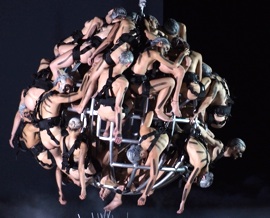

Opera lovers can see the precedent-setting and brilliant Valencia Ring cycle in its second installment, Wagner’s Die Walküre, and Bartlett Sher’s new production of Offenbach’s Contes d’Hoffmann with Anna Netrebko. Never been to La Scala? You can hear and see its production of Monteverdi’s Orfeo. Dreamed about going to Salzburg to see an opera? Watch its production of Mozart’s masterpiece Così fan tutte on Nov. 8. Want to see why audiences booed the Met’s new production of Tosca? Find out on Oct. 10. The huge screen and clarity of digital sound in a movie theater sympathetically enhance an opera’s characters, story lines, and music, which are already larger than life. Cinema’s intimate visual range reveals the details that contribute to the organic unity and integration of arts, making it clear why opera is the grandest of all art forms. But on the big screen, acting becomes a crucial aspect of the singer’s range of theatrical skills. “When you see two opera stars kissing (or groping each other) on the huge canvas of a movie screen, it needs to look real, or movie credibility is lost,” Cozzi adds.

In its 2009-2010 season, the Metropolitan Opera will be showing no fewer than nine opera productions live from New York City on Saturday mornings, with repeats on Wednesday evenings. One opera-movie fan sitting next to me at an earlier Met production enthused, “I no longer have to drool about going to New York to see the Met.” See here for Bay Area broadcasts at independent theaters in Santa Rosa and Larkspur and at national chain theaters.

The Vanishing Proscenium

The Metropolitan’s series, called The Met: Live in HD, along with most other opera-movie productions, has gone beyond the basic proscenium-frontal view, which is what most audiences would see from a seat in the opera house. Indeed, the cinematic techniques used by film directors of opera movies bring the audience new perspectives. Editing the film images to the ebb and flow of the music, using close-ups, and shooting from various camera angles can give dramatic impact to a scene. In the Met’s recent transmission of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor (last Feb. 7), as Anna Netrebko sang the heroine’s famous cabaletta, “Quando, rapito in estasi” (When, rapt in ecstasy), the camera slowly zoomed in on her face to the thrilling moment when she reached a high C. “You can see every expression on the singers’ faces, making them much more human and rendering the music even more emotionally available,” commented one opera-moviegoer.

much more human and rendering the music even more emotionally available,” commented one opera-moviegoer. Using tracking shots and quick edits can emphasize character relationships. In the sextet of the second act of Lucia, the cameras cut back and forth between individual characters and their groupings, from angles above and below, creating a visual rhythm that magnified the music’s emotion. The use of camera angles shot from below the stage is a device that film directors use to heighten drama, making the characters and their psychologies monumentally universal.

As a wonderfully entertaining and educational feature, the Met also introduced live interviews, during intermission, with opera stars and production staff. In the 2008 showing of Britten’s Peter Grimes, soprano Natalie Dessay interviewed principals Patricia Racette (singing the role of Ellen Orford), Anthony Dean Griffey (Peter Grimes), Met Chorus Master Donald Palumbo, and costume designer Ann Hould-Ward during the first intermission. A filmed BBC short-subject on Britten and Peter Grimes in an Aldeburgh production was also shown after the first act. After the second intermission, Dessay interviewed the production’s director, John Doyle, and set designer Scott Pask. Live interviews also can reveal delightfully unrehearsed moments. A surprised but tickled audience giggled at Karita Mattila’s exclamation, “Let’s kick some ass,” before going on stage to play Salome in the Met’s transmission of Strauss’ opera.

The View From Above

The new technology can be put to other uses, as well. San Francisco Opera’s venture into high-definition video, which it named OperaVision, wasn’t originally intended to be shown in movie theaters. “From the beginning, we designed the digital transmission of our operas to support the visual perspective of our balcony audiences, so we built the first in-house digital production center in the world to do that,” said Jessica Koplos, SFO’s director of electronic media.

The new technology can be put to other uses, as well. San Francisco Opera’s venture into high-definition video, which it named OperaVision, wasn’t originally intended to be shown in movie theaters. “From the beginning, we designed the digital transmission of our operas to support the visual perspective of our balcony audiences, so we built the first in-house digital production center in the world to do that,” said Jessica Koplos, SFO’s director of electronic media. Two screens, each 5½ by 10 feet, one on either side of the opera house’s proscenium at balcony level, provide close-up views with subtitles, which offer the audience a choice of watching the distant stage, the screens, or both. When having to choose between the faraway stage and the immediacy offered by the video screen, I couldn’t take my eyes off the faces on the screen.

“Seventy percent of the audiences surveyed in 2007, when we started OperaVision, approved of the choice,” said SFO’s Marketing Director Marcia Lazer. “We liked the results so much, we decided to show four operas in movie theaters. Now we’re showing them to theaters and nonprofit arts centers in the western part of the United States,” Koplos commented. These are the same, free, live simulcasts that are also shown to large audiences in San Francisco’s baseball stadium, AT&T Park (see SFCV’s recent profile with patron photos).

To be sure, opera in the movie theater has its disadvantages. The sound can vary from excellent to adequate, depending on the theater’s sound system. The biggest sonic annoyance is hearing the soundtrack from adjacent films bleeding into the opera-movie’s theater, especially deep bass, which can be intensely felt and heard. Sometimes the live satellite transmissions are briefly lost, eliciting a collective moan and grumbling from the audience. Most theaters showing operas have stadium seating, so blocked views are not an issue. Of the 23 operas in movie theaters I have attended, audience behavior rarely interrupted the performance, and popcorn crunching seldom broke the audience’s concentration.

Live opera as movie is a new and exciting art form, though it still can’t reproduce the frisson between performers and audience or the acoustical ambience of air and space around instruments and singers in a live performance. Companies hope that expanded movie audiences will choose to take in live performances, as well, just as the Met encourages in its traditional Saturday morning radio broadcasts. Thus, even as the artful use of technology expands the menu of choices in operagoing and brings the world’s great opera companies to your neighborhood, everything comes back to the stage itself. After all, the movie can only be as good as the show it transmits.