In the case of pianist Gloria Cheng, the business world’s loss has decidedly been the music world’s gain. Indeed, Cheng, who was once hailed by The New York Times as “an invaluable new-music advocate and a preferred collaborator of composers like Pierre Boulez and Esa-Pekka Salonen,” upended her parents’ master plan by earning a bachelor’s degree in economics from Stanford University and then pursuing a career in music. All the same, the pianist’s chosen path has proven artistically rich.

Her talents will be on full display at Zipper Hall on Oct. 21, when Piano Spheres and the Angel City Jazz Festival present “Gloria Cheng’s Root Progressions,” a program that explores the thrilling nexus of classical new music and experimental jazz. Cheng is also hosting a free related workshop at UCLA at noon that day.

While her career choice may have been a surprise to her parents, music was not entirely foreign to the New Jersey native, who studied piano with her mother from the age of 4. Training under the tutelage of Isabelle Sant’Ambrogio followed, and Cheng went on to earn graduate and postgraduate music degrees at UCLA and the University of Southern California.

On the faculty of the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music for nearly two decades, the Los Angeles-based pianist has been a concerto soloist with the LA Phil under Boulez and Zubin Mehta and on its acclaimed Green Umbrella series with Salonen and the late Oliver Knussen. As a recitalist, Cheng has performed at the Ojai Music Festival (where she began her association with Boulez in 1984), Chicago Humanities Festival, Tanglewood Festival of Contemporary Music, and annually for the L.A.-based Piano Spheres series, where she’s an emerita artist.

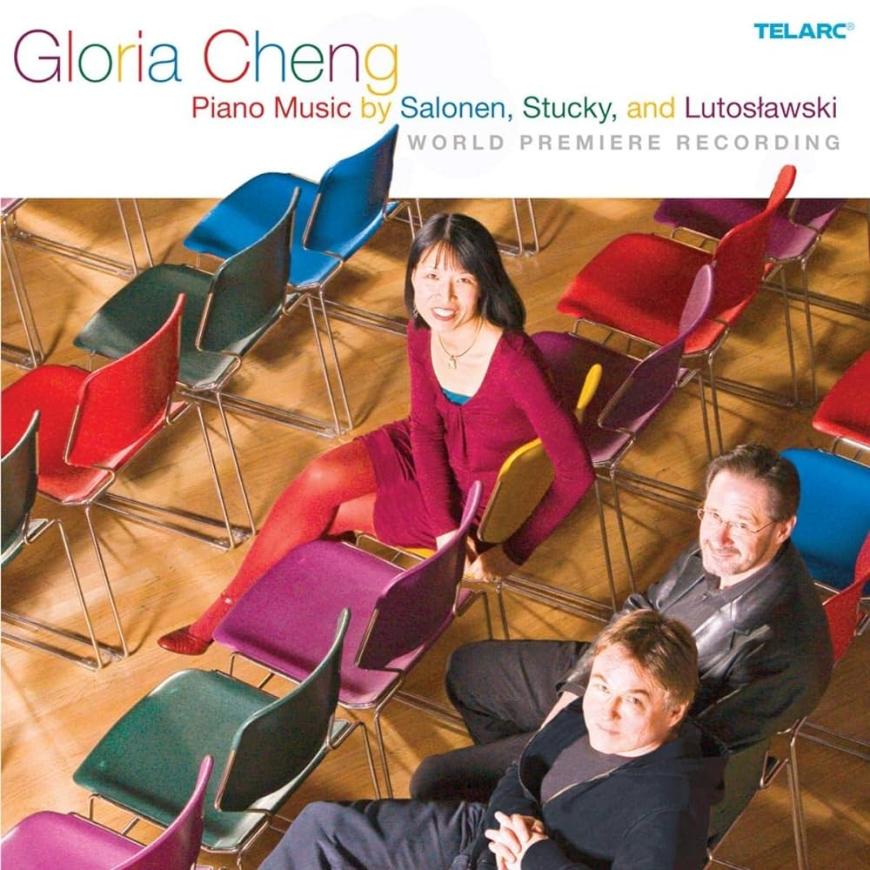

Cheng has premiered myriad works, including John Williams’s Prelude and Scherzo for piano and orchestra, Salonen’s Dichotomie (dedicated to her), John Adams’s Hallelujah Junction for two pianos (written for her and Grant Gershon), and Steven Stucky’s Piano Sonata. Cheng won the 2009 Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance for her recording Piano Music of Salonen, Stucky, and Lutosławski and was nominated in 2013 for The Edge of Light: Messiaen/Saariaho.

Then there’s the musician’s foray into film. Cheng’s project Montage: Great Film Composers and the Piano won numerous festival awards and aired on PBS SoCal, subsequently snagging the 2018 Los Angeles Area Emmy Award for Independent Programming. Adept behind the scenes as well, Cheng produced “Music at Black Mountain College” for the Hammer Museum’s related exhibit, “Beyond Music: Composition and Performance in the Age of Augmented Reality” at UCLA, and “Inside the (G)Earbox,” a daylong UCLA symposium marking the 70th birthday of composer John Adams.

SF Classical Voice caught up with the super-industrious Cheng, discussing the “Root Progressions” program, her memories of Boulez, and what makes a composition “pianistic.”

The Angel City Jazz Festival has been going since 2008. You’ll be performing six newly commissioned works by, among others, Anthony Davis, Jon Jang, James Newton, and Gernot Wolfgang. Have you participated in the festival before, and when did you first become interested in jazz?

I’ve attended but not as a jazz pianist. I’m excited about being on a jazz festival — it’s a first for me. These are [composers] who are known in the jazz world — some are [also] known in the classical world — but all are known in the jazz world. This is a natural place for them to be, and it’s not so natural for me. But I’m excited about it.

It’s a hybrid, and I hope more jazz festivals will be open to this. It’s exactly the intersection I’m interested in — that place where musical thought overlaps. But music gets divided by genre labels because of record bins that [historically] needed a label. Audiences are different, [and] fans tend to be different.

Why do classical musicians, yourself included, shy away from improvising?

It’s not part of classical training anymore. But if you think of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Franz Liszt, they were all improvising. They composed and performed. That’s what they did. The idea of the performer-composer, that’s much more rare nowadays. I’m inspired by it and always have been. I started out easy [in jazz], listening to Oscar Peterson, Herbie Mann, and moved on to the more experimental stuff, which is where a lot of these six composers are coming from.

I can understand the attraction [of improvisation]. You never know what’s around the corner, in the next measure or the next piece. There’s always this element of surprise. There are parallels [to jazz] with what I’m doing [in contemporary classical music]; we’re all on parallel tracks. Both so-called genres are all about innovation, the individuality of the composer, experimentation, freedom, surprise, and extended harmonies and dissonances. If you listen to [Arnold] Schoenberg and [Tōru] Takemitsu, the harmonies are close to what you hear in a Bill Evans solo.

[Before this program] I felt very close to that world in that I wish I could do that. This is the reason I embarked on this: to take [jazz composers] out of their box — to actually notate a piece — and to take me out of mine. They composed oodles of notes to be played on the keyboard, no plucking, knocking, harmonics, et cetera. In light of the “everything’s already been done in writing for piano” creed, writing good notes is hard to do. But they did it, and they all sound individual and original.

[As for] improvising, I’ll do very little [because] the pieces are largely fully notated. That’s my job. We will also have two [jazz sets]: [composer and pianist] Jon Jang and [saxophonist] Hitomi Oba will close the first half, and [composer and bassist] Linda May Han Oh and her husband, [pianist] Fabian Almazan, will be closing the concert. Both traditions are going side by side. I’m excited about it. It’s kind of rare [to have these] conversations onstage.

It’s safe to say, then, that your passion for jazz is long-standing and also runs very deep.

I’ve always loved jazz and always envied jazz performers — and rock performers — any kind of people who get to do it in the moment. [They] make it up as it comes and have that kind of brilliant imagination as they think of it — the freedom, abandon, and joy. I’m always having to look at a score. I don’t have time to memorize with a multiple-composers project like this. I’m looking at an iPad and don’t have the freedom that [other performers] do.

The joy is something I just envy. I can feel it inside, but I can’t get too carried away because I have to get the right notes. There’s a huge difference in a performance piece — [something standard like] Yuja [Wang] doing Rachmaninoff. It’s ecstatic, it’s great, but I don’t have time to do that with the [new] repertory I’m doing. But I do try to bring joy, freedom, spontaneity. It’s a different mindset.

Pierre Boulez passed away in 2016 at age 90. What are some of your memories of him?

I worked with him a lot when I was playing extra with the LA Phil — those were great times — for around 20 years. There were so many wonderful people I got to work with through my association with Green Umbrella: [Witold] Lutosławski, Kaija [Saariaho]. We’re lucky to have a series like that. Boulez was coming through every two to four years when he and [late LA Phil Executive Director] Ernest Fleischmann were very close.

Boulez would come at the end of the season, and then he’d take us to Ojai. Those were challenging weeks. It seems as if every time he came, there was some last-minute change that seemed to affect me more than anybody else. When [Olivier] Messiaen died in 1992, suddenly I had to learn the Quatre Études de rythme, which are really difficult. There were always programming changes, and I would have to learn a new part on a few days’ notice.

I think [Boulez] appreciated how hard that was on me. [In 1996] I slipped to him that I was getting married, and he ended up writing this little piece for me that I absolutely cherish: Courtes dérives à partir d’Éclat. The title makes use of pieces that I played with him, and the music itself references some of the pieces. It arrived by fax in the middle of the night. I knew he was going to do it but wasn’t sure he would come through. There was the whirring of a fax, and I ran over. “Oh my god, this is it! He did it.” I played it in my bridal regalia, and I put it away thinking it was some sort of a private gift and I shouldn’t exploit it. The guests were duly surprised, [and] I treasure that he took the time to do that.

Wow, that is so cool! So, when you commission a piece, what do you look for, and what has it meant to have worked with so many great contemporary composers, including Salonen, John Adams, Terry Riley, and the late Steven Stucky?

I’m a bit chagrined that they’re all white males [whom you mentioned]. But it’s an honor when they say yes. I never know what I can expect, but what I can go on are their past records, and I do love and respect their music. That would be the thing that drives me to request a piece from them.

There’s a back-and-forth over notation, but that’s not interesting to talk about. I don’t impose any kind of [criteria], but sometimes I have to do a time restriction — that it can be 10 minutes or less, that kind of thing. If it’s going to be on a CD, it has to work out in terms of time. I miss having a CD player in my car [and choosing] a CD to bring on a certain trip — that was easy. But having to transfer it to my phone — I can’t talk to a computer. Siri? That’s beyond me!

What makes a composition pianistic?

I think a piano piece being pianistic is not a concern anymore, [and] I can respect that. It makes my life a little more difficult, but what I find [is that] 99 percent of the things I play have little to do with my training when I was young and getting my technique together. It has nothing to do with Chopin etudes, playing all the major and minor scales.

What I do stretches me far from those scales, the skills I acquired as a beginning pianist. It’s challenging mentally, as well as what it does to my hands sometimes. Some things don’t fit, but I have to find a way to get around it. Ultimately my brain is expanded for having done so. With enough practice, [a piece] comes. Sometimes it takes a lot more practice, but I respect the fact that composers are thinking beyond what a pianist is capable of. I welcome it.

What advice do you have for aspiring pianists — or composers, for that matter?

Aside from the obvious — to be really honest with yourself as a composer, as a pianist — to keep your ears open. Keep searching. So many pianists confine themselves to the same repertory that so many generations of pianists have already played. I encourage them to keep looking and see what strikes lightning for them. I love being surprised and sometimes even shocked by something new [just on account of the fact] that it even existed or could exist but it’s amazing music. Stay open-minded and continually curious.